Carrie Arnold is a freelance science writer from Virginia. She covers all aspects of the living world and has written for a variety of publications including Mosaic, Aeon, Scientific American, Discover, National Geographic, and Women’s Health. This story originally featured on Undark.

As a Lyme patient, Jennifer Crystal has a lifetime of experience dealing with severe illness. So when the 42-year-old writer and patient advocate came down with what appeared to be a mild case of food poisoning in early March, she cancelled her weekend ski trip to New Hampshire, but otherwise shrugged it off. However, when the dizziness gave way to a fever, and vomiting became a racking cough, Crystal began to worry.

Her illness began just as Massachusetts declared a state of emergency due to COVID-19, and because her use of public transit put her in contact with so many people each day, she couldn’t shake the feeling that she was becoming another coronavirus statistic.

Her primary care doctor advised her to get tested, which is where she, like nearly all Americans, began running into roadblocks. “I kept getting denied because I hadn’t been out of the country,” Crystal says. “It didn’t matter if you had all the symptoms.”

After several days of phone calls to health departments and the governor’s office—and as national news reports began documenting the proliferation of inaccurate or inconclusive COVID-19 tests—Crystal finally found a hospital emergency room that would test her since her immunocompromised status put her at high risk for severe disease. After taking a nasal swab, the doctor sent Crystal home to wait for the test results. When Crystal’s COVID-19 test turned up negative, her primary care physician said it was likely a false negative.

And that, Crystal says, is when the parallels to her experience getting diagnosed with Lyme disease years ago—a long journey marked by a vague menagerie of symptoms and a gauntlet of inadequate, inaccurate tests—first began sinking in.

Back in the early 2000s, when she first began looking to get tested, for example, she found that the test doctors relied on wasn’t that accurate. According to Brian Fallon, director of Columbia University’s Lyme and Tick-Borne Diseases Research Center in New York, in areas where Lyme disease is less common, doctors have to rely much more heavily on positive test results to diagnose it. That’s especially true if patients don’t have the bullseye rash— known medically as erythema migrans—characteristic of Lyme disease. Fallon also says that the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) didn’t always make clear that the vagaries of testing meant that their case counts were likely dramatically underestimating the burden of Lyme disease in the US.

Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, others in the Lyme community have begun recognizing some of these same similarities, too. “It was well known that only 10 percent of [Lyme] cases were actually reported to the CDC,” said Fallon. “But they needed to rely on traditional methods, which required positive blood tests or physicians’ records indicating the clinical symptom of erythema migrans. So the CDC numbers were always 10 times less than the actual rate, but the CDC wasn’t explicitly saying this.”

“The same thing is true for COVID-19,” Fallon added. “If you only report cases of people who have been tested, and the tests are not widely available, then you’re going to have a low rate.”

To Crystal, the one bright spot in the coronavirus testing debacle is that it has helped to educate the wider public on issues relating to diagnostic testing—something those in the trenches of Lyme disease when it first began to emerge decades ago had already learned.

While encouraged by the speed with which trials and vaccine development have gotten underway, Fallon noted that there’s still a long way to go. “I think we as medical students who go into medicine thinking that science is so advanced and it knows so much,” he says. “But over the last 30 years, I’ve learned that, yes, science has learned a lot, but it still needs to learn a vast amount more.”

Diagnosing Lyme disease has always been challenging. Similar to COVID-19, Lyme disease can cause a range of symptoms, such as rash, fatigue, joint pain, facial paralysis, heart problems, dizziness, and more.

“These symptoms are subjective and nonspecific,” says Timothy Sellati, chief scientific officer at the Global Lyme Alliance, a nonprofit Lyme disease research group for whom Crystal writes a weekly column, “and so it makes it very, very challenging for a physician to do a differential diagnosis and make certain that this individual has Lyme disease and not chronic fatigue syndrome, not multiple sclerosis, not ALS, and not influenza.”

As a result, physicians have had to rely even more than usual on laboratory-based tests to diagnose Lyme disease. On October 28, 1994, a group of scientists gathered at the Hyatt Regency in Dearborn, Michigan, for the Second National Conference on Serologic Diagnosis of Lyme Disease. Their goal was to hash out a standard testing strategy for Lyme disease.

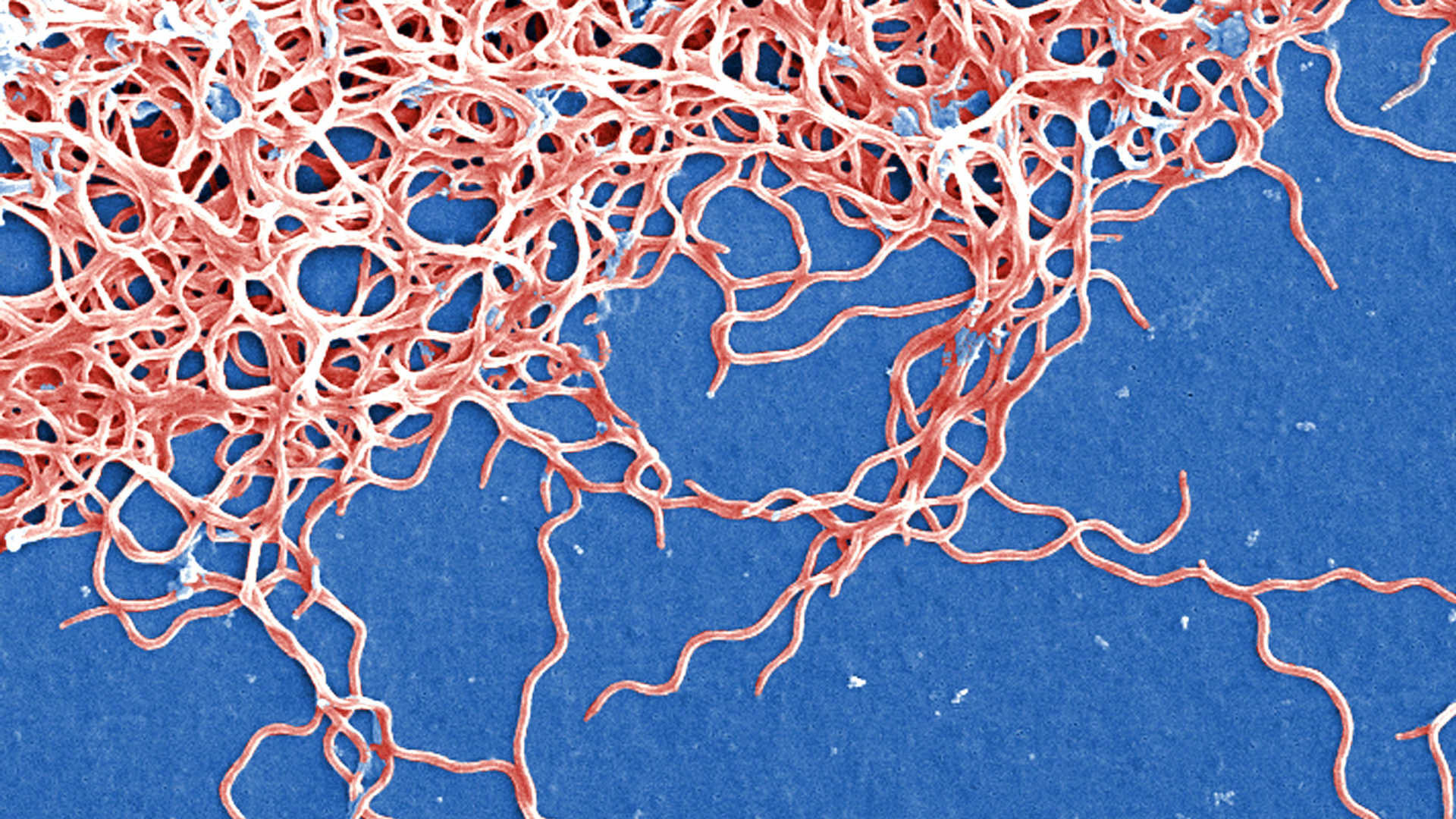

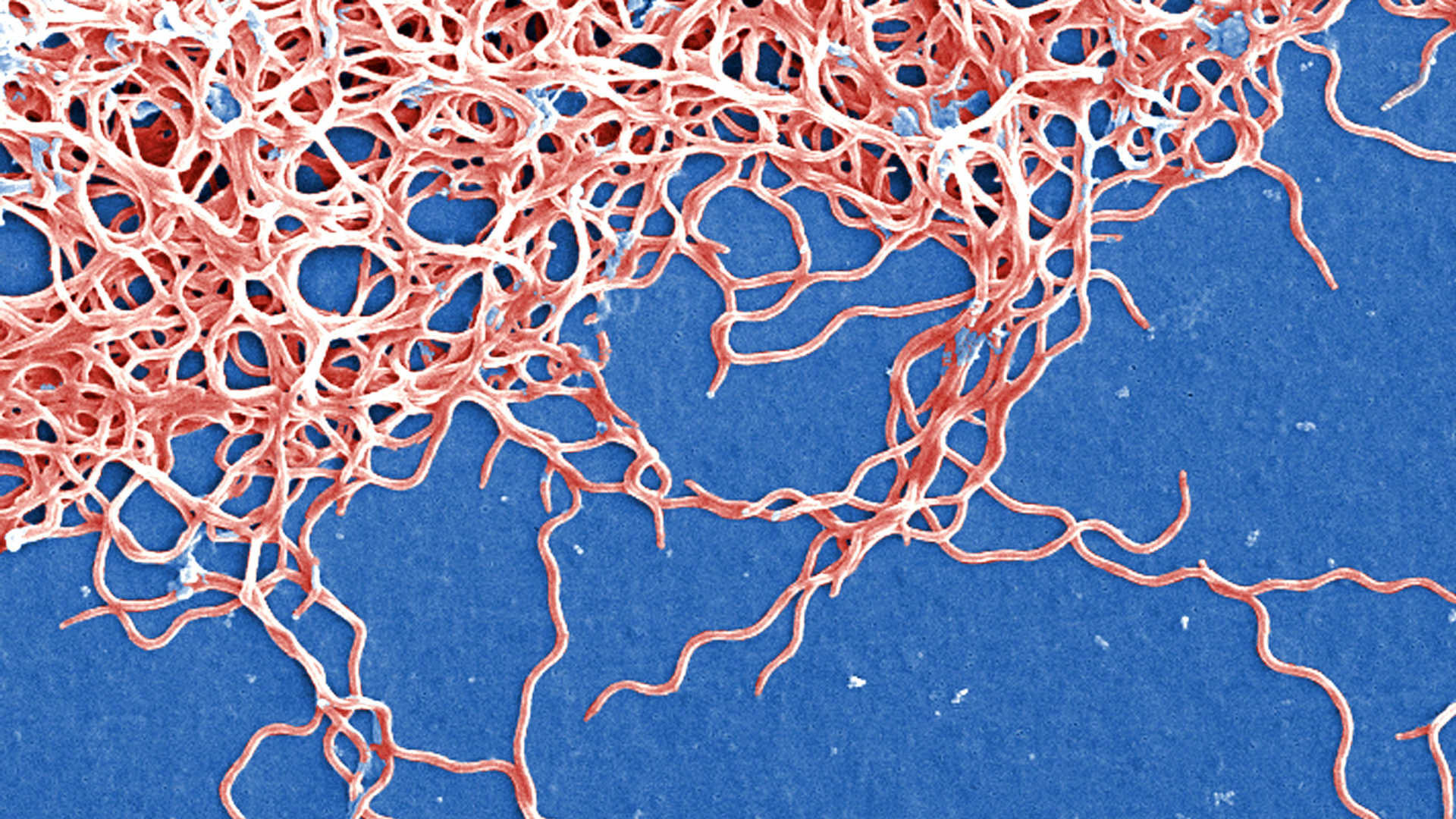

Ever since Lyme disease was identified in 1982 as a bacterial infection caused by Borrelia burgdorferi and spread by Ixodes ticks in the US, researchers had struggled to develop a laboratory test to help diagnose the condition. Historically, microbiologists had directly cultured disease-causing bacteria, but that didn’t work for Lyme. For one, B. burgdorferi is nearly impossible to grow in the lab. And even if it did readily grow in culture, the bacterium itself is only present in blood transiently, and in low numbers, so getting a sample would be problematic. That meant that directly identifying the Lyme disease-causing pathogen would be difficult. So researchers instead began looking at indirect ways of identifying Borrelia, such as searching for antibodies produced by the immune system against the bacterium.

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) detects antibodies produced against specific pieces of protein from Borrelia, known as antigens. ELISA tests are fairly sensitive, which means that people who actually have Lyme disease are likely to test positive. The problem is that these tests aren’t very specific and give a high number of false positives (that is, not everyone who has a positive ELISA actually has Lyme). The other major type of antibody test in the early 1990s was the Western blot, which detects antibodies against a set of different Borrelia proteins. The Western blot is specific, such that people without Lyme reliably test negative, but not very sensitive.

By the time of the 1994 Dearborn meeting, manufacturers had developed a range of different indirect tests for Lyme, none of which produced the kind of definitive results needed to help diagnose a disease that could mimic a huge number of other conditions. What resulted from the meeting was the two-tiered testing protocol, in which a positive or equivocal ELISA would be followed by a Western blot for confirmation. Subsequent studies, however, showed that even this two-tiered approach didn’t always adequately catch all cases of Lyme disease, although newer approaches are trying to change this.

“Diagnostic tests are never perfect. And now folks who are journalists and people in the public are at this time becoming educated as to the challenges and limitations of technology,” says David Ecker, vice president of strategic innovation at Ionis Pharmaceuticals, who has also worked on molecular tests for other pharmaceutical companies. “They are not perfect. They never will be.”

After the Dearborn criteria were announced in August 1995, the Lyme community began to point out their weaknesses. One difficulty was the fact that the tests relied on antibodies. Antibiotic treatment in the early stages of disease was the shortest and offered the greatest chances of cure, but the body doesn’t produce antibodies to the Lyme bacterium immediately after infection. It is, Sellati says, a major issue with testing for antibodies to any pathogen, not just Lyme.

“At the start of an infectious disease—and this is whether it’s a bacterial infection or a viral or even a fungal infection—you have very few antibodies,” he says. “The level of antibodies circulating in your bloodstream may be very low. It might be below detectable levels, but the longer you’re infected, the more time your immune system has to develop antibodies.”

Patients were also unsatisfied with the two-tiered protocol. The International Lyme and Associated Diseases Society (ILADS), a nonprofit medical group that has garnered controversy by releasing its own treatment guidelines that counter those from the CDC, says that “even when the tests perform well, some cases will be missed if we rely solely on test results.” In 2004, years after her likely tick bite and first symptoms, Crystal says her first Lyme test came back negative.

A year later, however, she says a repeat Western blot returned positive results for borreliosis, along with two other tick-borne diseases, ehrlichiosis, and babesiosis. As a patient advocate, Crystal says she has heard stories from patients who were told they couldn’t have Lyme because their tests were negative.

While she now describes her diagnosis as late disseminated Lyme disease—meaning it was not promptly or effectively treated—other patients who receive early care also describe lingering illness, for which the ILADS sometimes recommends long-term antibiotic treatment. Studies haven’t yet established whether this chronic Lyme is caused by lingering bacteria, an abnormal immune response, or both, nor have formal studies identified any effective treatment.

Because Lyme disease has historically been concentrated in the Northeast and in parts of the Midwest, where formal research had established both the Borrelia bacterium and the tick that transmitted it lived, doctors had more familiarity with the disease and its symptoms, according to Sellati. But in parts of the southern and western US, Crystal says that doctors frequently dismissed Lyme symptoms and would refuse to test. As with her COVID-19 experience, she says difficulties with getting tested meant that official case counts were likely much lower than the true number of people infected.

Similar to Lyme tests, those for the novel coronavirus have also been plagued with a series of issues. The very first diagnostic test for COVID-19 the CDC developed and distributed was designed to identify genetic material from the coronavirus, but laboratory contamination issues meant that the first set of tests were fatally flawed. Ongoing shortages in these test kits have meant that people with COVID-19 symptoms still don’t know whether they’re infected.

By early May, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration had granted several antibody tests for COVID-19 an emergency use authorization. But these tests, too, had issues. The biggest problem, both for public health agencies and the general public, were the possibility of false positives and false negatives. This highlights the challenges of antibody testing in general, according to Sellati.

“If you have a negative result, don’t take it at face value that you are truly negative, especially with the serological testing,” he says. “You should maybe wait a few weeks to give the immune system a little bit longer to perhaps produce antibodies.”

Such are the lessons in diagnostic testing that people the world over are now learning. As with her first Lyme test, Crystal’s COVID-19 test also turned up negative. “I guess it could be some other respiratory illness,” she says. “But if it walks like a duck, talks like a duck, and there’s ducks replicating all around,” she quips.

This time, however, the medical community and her friends and family had a different response when she expressed skepticism at the negative results. Instead of objecting when Crystal raised questions, her doctor and social group agreed with her assessment that the coronavirus test was likely a false negative. If one good thing comes out of the pandemic, Crystal says, it’s that people start thinking more critically about any sort of laboratory test.

“You have to fit into this very clinical box to be considered a COVID patient, even if you have all the symptoms and otherwise, you know, clearly seem to be one,” Crystal says.

“What I learned from Lyme disease,” she adds, “was you have to treat the patient, not the test.”