Three test pilots. Two flight surgeons. One molecular biologist. A flight controller, a Pentagon staffer and a CIA intelligence officer. These are the nine people chosen by NASA to be America’s next astronauts. Late this summer they reported to Houston along with two Japanese pilots, a Japanese doctor, a Canadian pilot and a Canadian physicist who will train alongside NASA’s class of 2009. Call them the lucky 14.

Selected from more than 3,500 applicants, NASA’s new astronaut candidates arrive at a pivotal moment in the history of human space exploration. The agency’s bold ambition is to rocket humans beyond the International Space Station for the first time in more than 40 years. The question is when.

In September, a panel of space experts and former astronauts chaired by former Lockheed Martin chief Norman Augustine told the White House that a budgetary boost of an estimated $3 billion annually would allow NASA to develop the necessary spacecraft to take astronauts to the moon, near-Earth asteroids and ultimately to Mars. Anything less, the committee concluded, would delay a moon landing until at least the late 2030s.

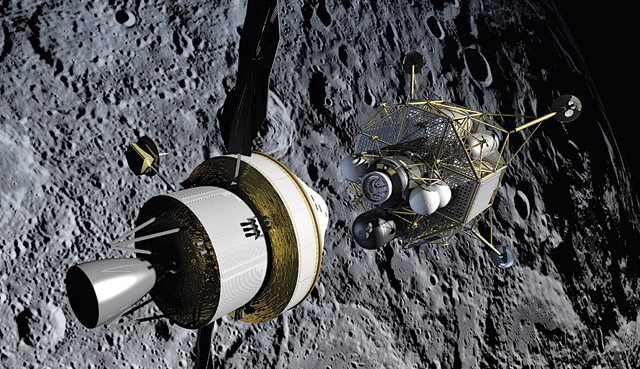

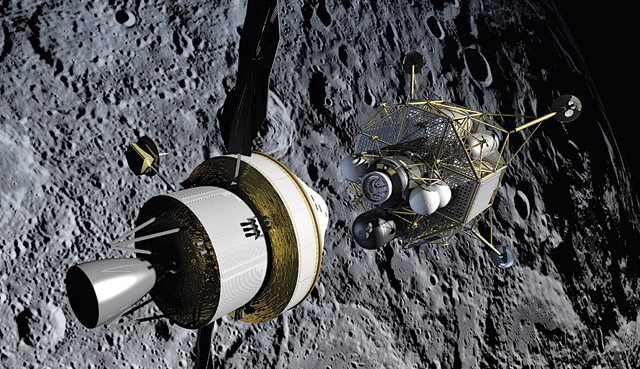

Whether NASA gets extra financial support from Congress or not, now is a crucial time for the agency to fundamentally reevaluate how it prepares its new recruits for the rigors of deep space. Plans call for the construction of a new crew capsule called Orion to replace the space shuttle in 2015, plus two rockets and a lunar lander. This suite of hardware, known as Constellation, is billed as the Swiss Army knife of space exploration, capable of flying to multiple destinations and performing multiple missions. And that’s what NASA expects of these future astronauts, too. They will be trained as jacks-of-all-trades who can do experiments on the ISS, erect an outpost on the moon, or collect samples from an asteroid that’s hurtling through space. They are NASA’s first new astronaut class in five years, the first chosen since the Constellation development program began, and the first ever to be chosen solely for long-duration missions in space. NASA isn’t just tasked with reinventing its hardware; to get beyond low-Earth orbit, it must reinvent its astronauts.

Tough and Cheerful

Like the astronauts before them, recruits will take an outdoor survival course in Maine, spend up to two weeks living in an underwater lab, endure altitude chambers, and struggle through flight mechanics. But for deep space, astronauts will need new training entirely, perhaps including spending weeks, even months, in confinement and isolation.

A trip to Mars will take humans so far from home that Earth will look no bigger than a star. The distance is so great that in a September New York Times op-ed, Lawrence Krauss, a theoretical physicist at Arizona State University, went so far as to propose that, to save fuel, astronauts perhaps shouldn’t come home at all. Apollo astronaut Buzz Aldrin, an ardent believer in the colonization of Mars, has also floated this idea. For a trip that long, intense psychological preparation is critical.

The Mars Society, a space-advocacy group, has conducted a series of simulated Mars missions involving 80 crews at a desert station and a dozen crews at an even more remote Arctic base. Robert Zubrin, the society’s president and author of The Case for Mars, recommends that NASA conduct experiments to see which astronaut teams work well together when tasked with field exploration in adverse conditions for months on end. “You put them through missions, and you see who is tough and cheerful and team-spirited,” Zubrin says. “If you lose your sense of humor on the way to Mars, you’re finished.” One of the most important lessons learned during the field missions is that some people perform well on one team but not on another. “It’s because of the mix,” he explains.

Jason Kring, an assistant professor at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University who studies the human factors of spaceflight, agrees with Zubrin that intensive training here on Earth is a must. He also suggests that NASA include a clinical psychologist on the crew to help mitigate potential conflicts. “What to us would be a minor problem in an office environment can become a big deal after six to eight months with the same people,” he says.

NASA is already making efforts to screen more carefully for psychological flaws, after the meltdown of Lisa Nowak, the shuttle astronaut who goes on trial next month for attempting to kidnap a fellow astronaut’s girlfriend. It’s not hard to imagine how such instability could sink a space mission.

While everyone in the class of 2009 has an advanced degree in engineering, science or math (“extensive experience flying high-performance jet aircraft” was also a plus), the most sought-after quality was the ability to play well with others. Today, an astronaut with the right stuff is someone who does not get frazzled or grumpy when he spends seven months trapped in a flying office with co-workers who may not even speak his language—an office in which his and his companions’ recycled sweat and urine is a beverage, the toilet clogs, and a serious mistake means they all could die.

Of course, astronauts will need extra preparation for the physical challenges too. During the trip itself, they will be subjected to high doses of radiation, raising their odds of getting cancer later in life, and they will lose bone density. “The worst-case scenario would be a Mars crew that steps off the vehicle and their bones are too brittle to hold their weight,” Kring says. He suggests that NASA may eventually need to create a new category of astronauts trained for “ultra-long-duration” missions. “Thirty-six months in space is a lot different than six months,” he says.

New School

Preparing for even a space-station or lunar mission takes several years. The 2009 class won’t be full-fledged astronauts until 2011, and they won’t fly their first space missions until at least 2014. “The intent of basic training is to get folks up to the proficiency they need to begin mission-specific training,” says Duane Ross, NASA’s manager for astronaut candidate selection and training.

Unlike the 12 astronaut classes selected in the past three decades, which were divided into a caste system of pilots and mission specialists, NASA’s newest class will be known simply as “astronauts.” Flying Orion is expected to be much less complicated than flying the shuttle. Many of the ship’s functions will be automated, recalling the days when Chuck Yeager called the astronauts “spam in a can.” Although the Orion missions will involve a crew of up to six instead of Apollo’s three, for long periods they will just be along for the ride. The glass cockpit interface, for instance, will have one tenth as many switches as Apollo.

Learning to pilot the space shuttle was in many ways the centerpiece of past astronauts’ training. The shuttle is “an incredibly complicated beast,” says Pam Melroy, a former shuttle commander who recently became director and deputy program manager of the Space Exploration Initiatives program at Lockheed Martin, the contractor building Orion. Recruits spent 54 weeks on shuttle systems during their two-year basic training, Ross says. Astronauts flying Orion won’t have to land on a runway, so the class of 2009 will instead spend more time learning things like Russian (since Russia’s Soyuz spacecraft will temporarily be the only ride to the ISS after the shuttle retires) and practicing extravehicular tasks in the world’s largest swimming pool. On the other hand, Orion will be a much smaller vehicle than the shuttle, so it will have less built-in redundancy. That means astronauts may have to spend more time training for equipment failures, Melroy says.

As with the shuttle, Orion astronauts will practice ascents in a full-motion simulator that forces them to make quick decisions about whether or not to abort a mission. They will also use simulators to learn how to dock with the ISS and how to fly the new lunar lander, Altair, down to the moon’s surface. The lunar-lander simulators for the Apollo missions looked like flying bed frames, Melroy says, and all of them crashed during training. “I think we’re going to have to do a little better than that,” she says.

Engineers are still working on the designs for Orion and Altair but, as in the Apollo days, astronauts are involved in the process at every step. Already astronauts have been invited into mock-ups of the crew capsule to see whether they can fit comfortably in the seats and reach the controls. “By the time astronauts actually get in and start using the mock-up, they’re already very familiar with it,” says Olivia Fuentes, the exploration-development laboratory section manager for Lockheed Martin.

Further down the road, astronauts will begin preparing for surface operations on the moon and, potentially, asteroids. A swimming pool can simulate the weightlessness of the ISS but not the moon’s gravity—one sixth of Earth’s. “We’re going to have to mix the water training with training on how to walk on the moon again, as well as on the Martian surface,” Kring says. The Apollo astronauts practiced their moonwalks in the Partial Gravity Simulator, an adult-size Johnny Jump Up suspended from the ceiling, and future astronauts may use an improved version of a gravity simulator called the “pogo.” Asteroids and Martian moons may require still more training facilities, and both destinations will demand a revamped space suit that can be worn for days.

Mind the Gap

NASA’s tentative plan is to retire the shuttle in 2010, but the Augustine committee estimates that Orion won’t fly until at least 2017, leaving a seven-year gap during which time no NASA manned spacecraft will take to the skies. And that leaves the agency trying to predict the future.

You don’t pick astronauts for today’s needs, Ross says. “You make your best guess about what’s going to be happening five years from now.” The class of 2009 is one of NASA’s smallest, and that’s a reflection of limited chances to fly in the future. Shuttle astronauts could expect to make several missions during their careers, but with a smaller vehicle, NASA will have fewer astronauts in space. Like many of the Apollo astronauts, the new recruits might make only one or two flights in their entire career.

So why become an astronaut at all? Astronaut recruit Kate Rubins has heard that question before. When she told her peers about her new career path, some of them questioned it, wondering why anyone would want to become an astronaut now. NASA’s future is so uncertain and everything in space seems to be in constant need of repair. Who wants to rocket 255 miles into space to fix a toilet? Aren’t you a tenure-track molecular biologist at MIT? Naturally, Rubins sees things differently. Through her eyes, NASA has an unprecedented opportunity. Many experts consider the ISS a training ground for more-ambitious adventures in space, and now that the facility is nearly complete, NASA may soon be free to turn its resources toward the next big chapter in its history: manned exploration beyond the ISS. The agency is already building a new ship for the job, rocket technology has never been more affordable, thanks to epic strides made by the private space industry, and increasing environmental threats to the planet make human outposts in space sound more and more like wise investments.

Today’s astronauts may take fewer flights, but the ones they do take could make history. It’s possible that someone in the 2009 class will be the next to set foot on the moon, or the first woman to ever do so. Some of them could even become the first to visit an asteroid.

Now is the perfect time to start preparing them for the trip.

What Do You Wear in Space?

Think of the new astronaut suit as a wearable spaceship, complete with a toilet

With its sights set on deep space, NASA has tasked Oceaneering International to develop the first new space suit since the shuttle “jet pack” of the 1980s. For lunar missions, the Constellation Space Suit System, or CSSS, will come in two configurations: one that the astronauts will wear aboard the spaceship during launch, landing and spacewalks; and a second configuration designed to be worn on the moon’s surface. The two suits will share many components, such as boots, legs, gloves, and cooling and communications systems.

The big challenge is designing a system for handling solid waste in the event that the crew capsule loses cabin pressure and the astronauts have to spend an extended period, even days, in their suits while the problem is repaired.

For long missions in deep space, astronauts must maintain their own suits, learning beforehand how to fix every port and sensor on them. “When you strap in for the real mission, you should feel like you’re home,” says Jim Buchli, the program manager for the CSSS at Oceaneering. “There should be no surprises. —Dawn Stover, with additional reporting by Carina Storrs

For a closer look at NASA’s new space suit, [see the image gallery here