Write Your Name on the Moon

New software from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory gives you control of a fleet of satellites, to harvest data or just play around

What do you get when you ask a former Disney animator and veteran NASA climate geomorphologist to help explain global change?

How about cartoon satellites and a laser that can write your name on Titan?

Using gaming technology, animators and programmers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory designed a 3-D, browser-based program that lets people fly along with 15 NASA Earth observation satellites in real time. The program, called “Eyes on Earth 3-D,” requires a plugin that’s compatible with almost any Web browser.

Click on each satellite to zoom in and you can follow its track across the globe in real time, in fast forward or in reverse. The satellites appear as they do in space, and every detail from the stars to the moon’s phase is taken into account. Click on the “car” button and a cartoon Porsche 911 appears next to the spacecraft to put its size in context.

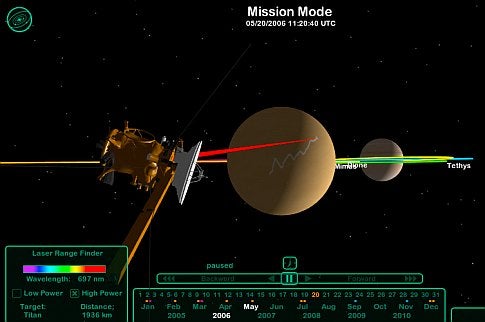

The program also includes Metropolis, a game that sends a subtle yet strong message about human-caused atmospheric carbon dioxide: Users compete to quickly uncover 10 major cities by erasing a shroud of CO2 enveloping Earth. And with CASSIE, the Cassini At Saturn Interactive Explorer, you can fly with the Cassini probe to Saturn and its moons, where you can use a “laser” to write your name on your chosen orb’s surface. It’s like NASA’s own version of Google Earth, only it’s based in your browser, and it includes the freshest possible data.

“We try to give the general public a virtual presence with our missions,” said Kevin Hussey, manager of Visualization Technology Applications and Development at JPL.

The programs are designed to highlight NASA’s work on global climate change and give the public and professional researchers better access to the agency’s wealth of Earth sciences data.

“We have a whole fleet of satellites that are monitoring the globe. But not long ago, when you did a Google search for global change, we didn’t come up until like page 10,” Hussey said.

NASA wanted to change that, and managers decided to use its own employees’ animation skills, rather than incorporating climate data into Google Earth.

“Now don’t get me wrong, I love Google Earth. I get excited about it. But there are just some limitations,” Hussey said. For one thing, its programming language isn’t designed to accommodate NASA’s massive data sets, and Google Earth doesn’t allow users to see the satellites that collected its images.

“Of course, our satellites are important to us,” Hussey said. Eyes on the Earth lets users hover above each probe so they can be seen in action; three key satellites, Aqua, CloudSat, and the Ocean Surface Topography MissionWeb are represented by 3-D cartoons.

A Google partnership may be in the works, however. A University of Utah program already incorporated CloudSat data into Google Maps, and Hussey said he was optimistic Google Earth would eventually add climate data, too. He demonstrated Eyes on the Earth’s capabilities at a recent conference, and Google representatives told him they should get together, he said.

“It’s just [a matter of] time. I predict that we will, in fact, be doing more work with Google,” he said.

The Aqua Satellite

Though he’s a climate scientist and geographer, Hussey has a lengthy background in computer animation, which led him from NASA to Disney and back. He started playing with imaging software as a graduate student at JPL, cobbling together images from Mars and moon missions and making time-lapse animations using data from the Landsat program. He eventually created the agency’s well-regarded science data visualization program in the early 1980s. In 1998, Hussey was recruited as a Disney animator and IT manager — in his eight years at the company, he worked on “The Hunchback of Notre Dame” and “Home on the Range,” among other films — but his heart belonged to JPL. When he returned, he wanted to find a new niche, something NASA wasn’t doing that could help the public understand its missions.

“Hey, I don’t know about you, but I get a kick out of video games,” Hussey said. “When we got started with this, it had nothing to do with the World Wide Web; it was about wanting to use computer gaming technology to help visualize our missions.”

Members of Hussey’s team already design movie-grade animations for projects like Mars Science Lab, so Hussey asked a colleague to create a new software system, or engine, to make them interactive. His colleague, Paul Upchurch, came up with a game engine that lets users spin Mars like a Harlem Globetrotter handling a basketball, using 112 full-resolution images from reconnaissance missions. The program allows for huge, detailed images, but include about 22 gigabytes of data — not exactly practical for most people. Hussey’s boss told him to make it smaller.

“He said, ‘Everybody that sees our work, locally, loves it. You really do feel like you’re riding along with this stuff. But you can’t bring everybody here,'” Hussey said.

Upchurch found a game engine called Unity that works inside Web browsers, and the team was commissioned to build a system for JPL’s global change Web site.

“They wanted people to experience, through the eyes of the satellite, what would it be like if we were there,” Hussey said. “We want to communicate to the general public what NASA is doing to understand global change.”

Hussey’s goal is to eventually include all NASA missions. “This is my dream, that you could click on any of our missions and see what they’re doing in real time. If you have a rover that’s roving on Mars, and the wheels are turning, you ought to be able to see that from Earth. We know the wheels are turning, because we told it to turn,” he said. “I want the general public to be able to access the missions in this very intuitive, user-friendly way.”

And who doesn’t enjoy writing his or her name in planet-sized letters?