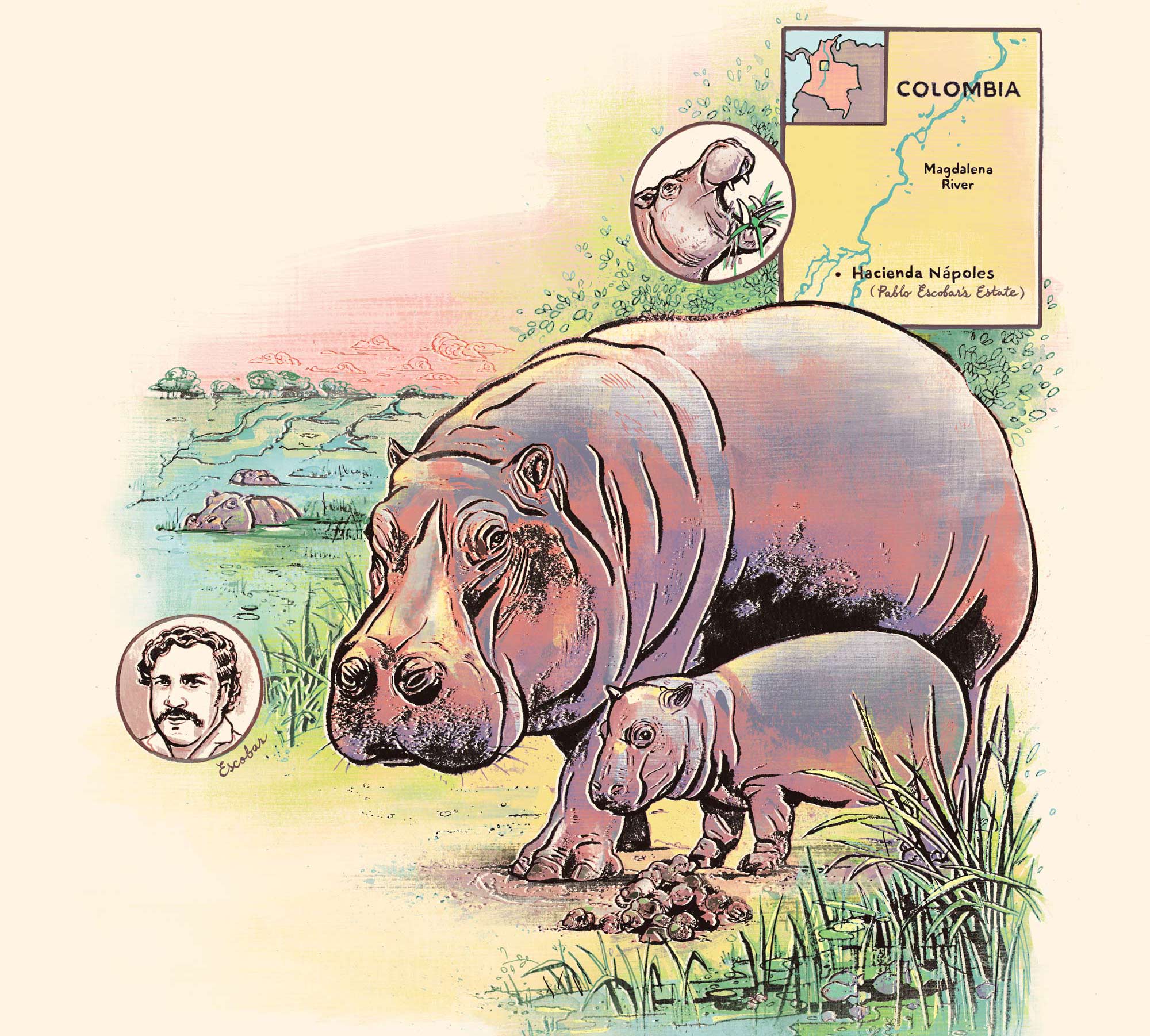

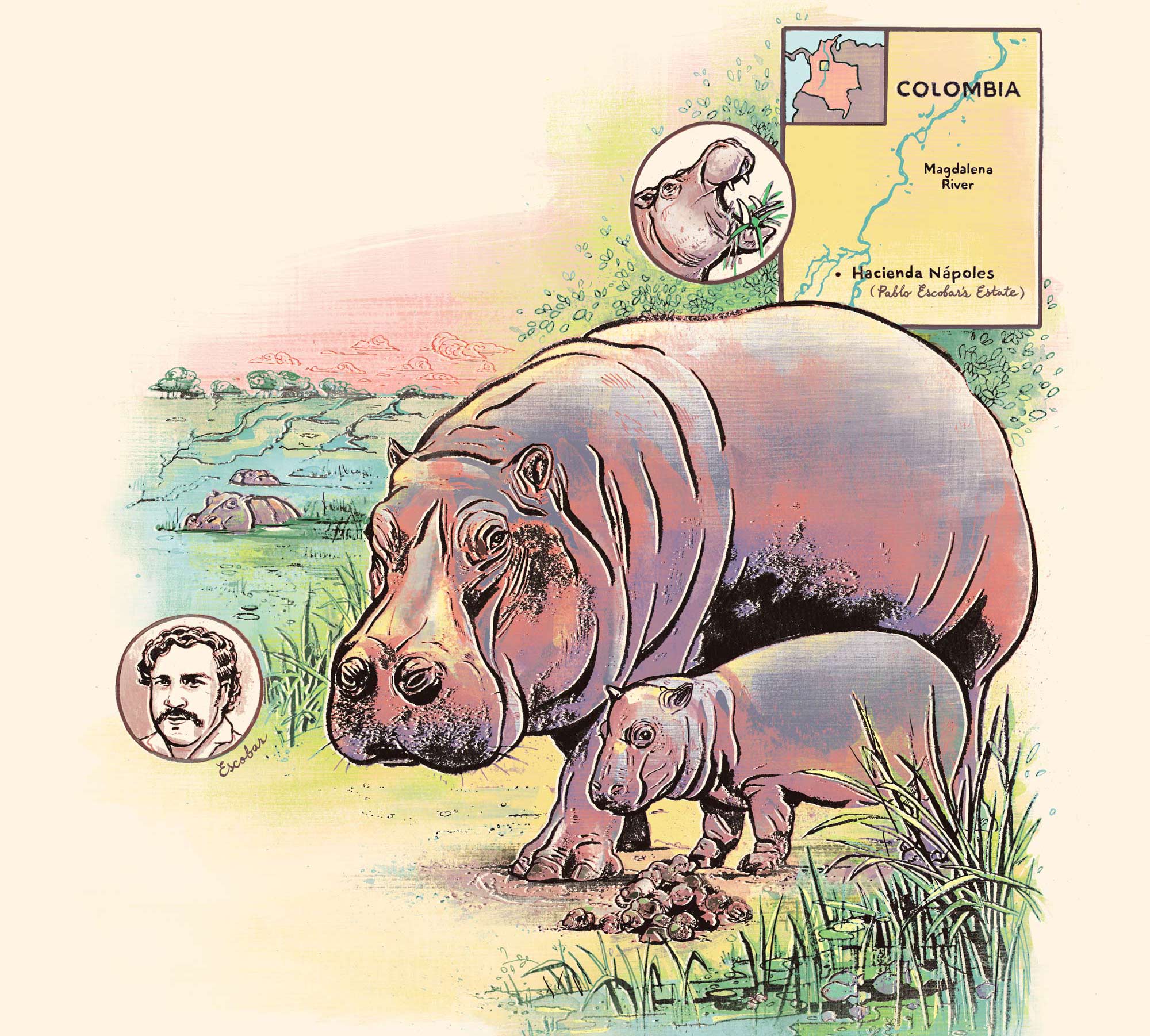

In 1981, notorious drug lord Pablo Escobar imported four hippos from Africa to his estate near Medellín, Colombia. After his death in 1993, the herd meandered into the nearby Magdalena River. Ecologists estimate there are now 65 to 80 swimming around, and that number could reach 800 by 2050.

Introducing new species often causes environmental mishaps. Toads released to eat crop-loving beetles took over Australia, and ivy brought to the New World for decoration has toppled native trees. But some ecologists think these hippos may have happened upon a valuable role: 100,000 years ago, semiaquatic hoofed mammals roamed South America, and Escobar’s pets may be filling the niche they left behind. Here are four ways they’re shaping their environment.

Forging paths

At a whopping 3,500 pounds each, hippos’ bodies are able to create trails through shallow rivers, altering flow. This forms stream-like waterways where small fish can hide from predators. Their survival supports a diverse ecosystem, which is generally more resilient than one with fewer species.

Snacking on shrubs

In Africa, these ungulates’ hefty appetites keep grass height in check, spurring new growth. Fresh sprouts are lower in fiber and higher in nutrients like nitrogen, making them the perfect snack for smaller grazers like vicuna. A similar, unconfirmed effect may be at play in Colombia.

Fueling fish

Hippopotamuses expel waste while wading, and their poop provides a feast for aquatic microorganisms—and in turn a boost for the fish that eat them. But invasive animals never come without complications; waste can also prompt algae blooms that drop oxygen levels, killing swimmers en masse.

Stomping around

The hooves of these chunky beasts dredge up sediment along waterbeds, resuspending organic matter that algae living close to the surface can feed on. All this stomping also forms small, deep pools where fish can find shelter during the dry season when the river level drops.

This story appears in the Winter 2020, Transformation issue of Popular Science.