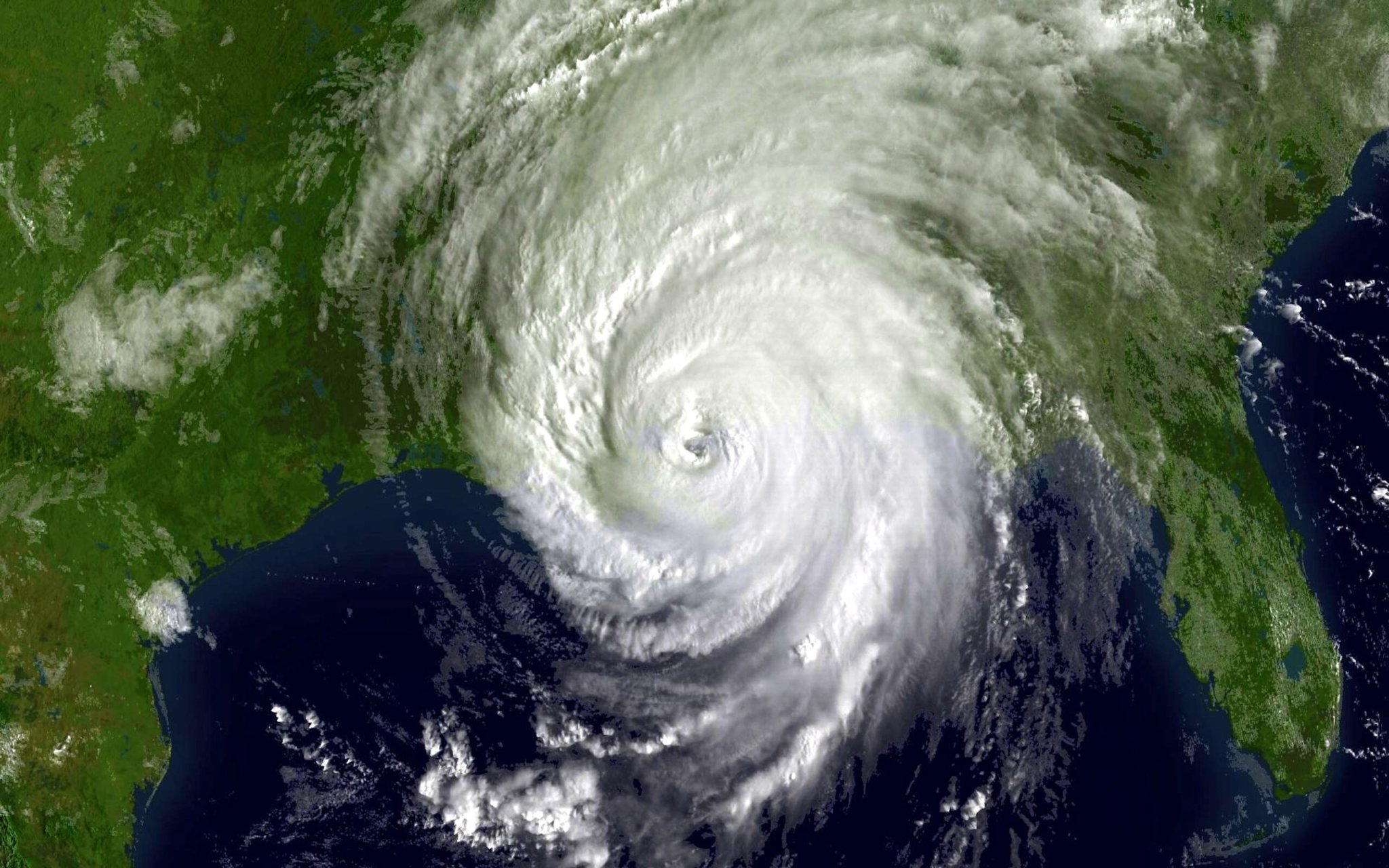

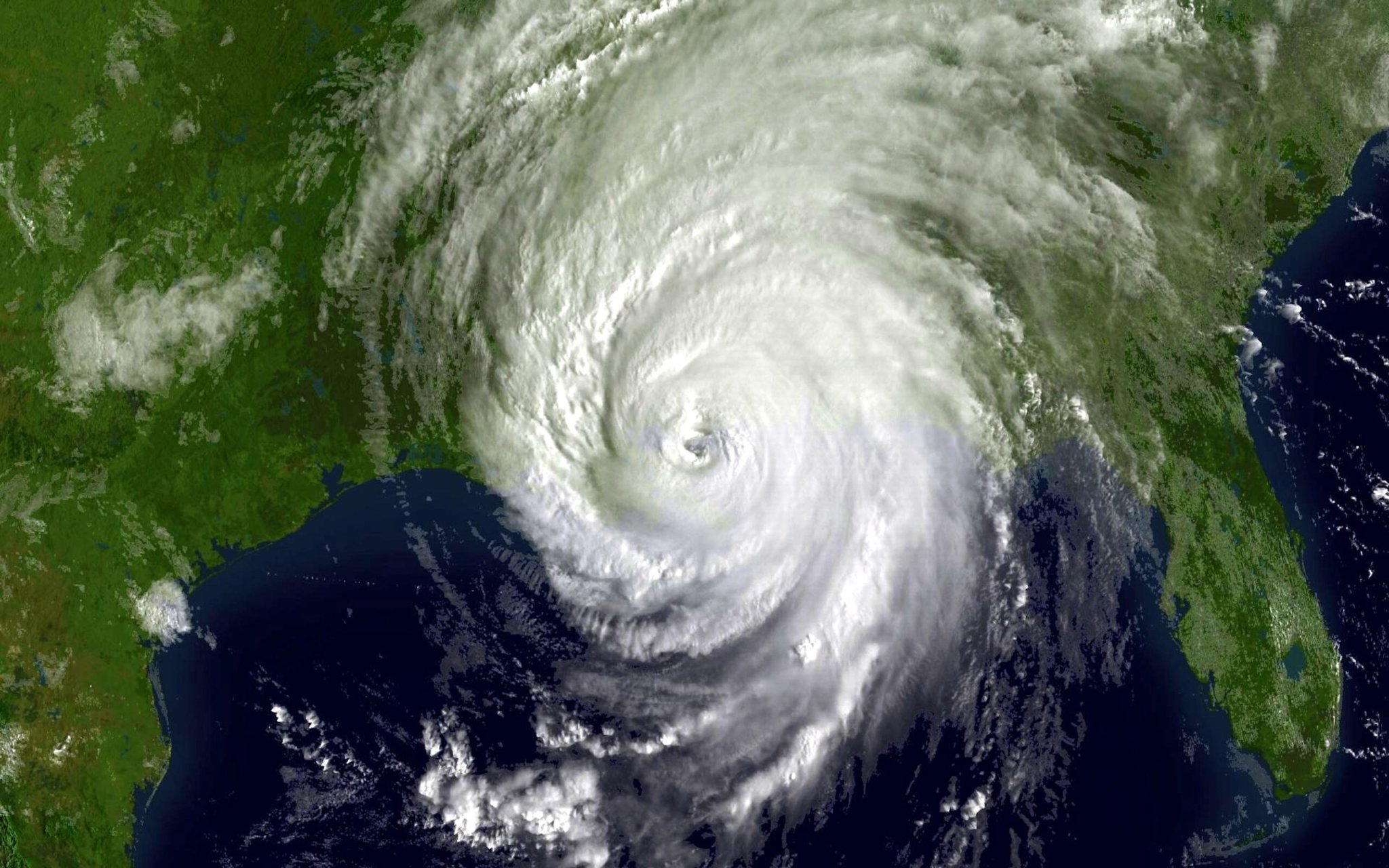

Officially, the record of hurricanes in the Atlantic goes back to 1850. But hurricanes have been going on for a lot longer than 166 years.

In a paper published this week in PNAS, researchers dug into history and added an additional 350 years of hurricane data to that record. Of course, they weren’t able to get down to the details of all the individual storms we see today using satellite technology, but the researchers were able to pinpoint years with major hurricanes going back to the year 1500 using two sources, tree rings and shipwrecks.

Trees, which can’t run away during bad weather, keep a record of storms, including hurricanes, in their tree rings. Tree rings are the concentric rings that you see when you cut into a tree. They grow over the course of a year, which lets researchers called dendrochronologists determine the age of a cut tree. But tree rings also contain much more interesting information. The tree rings vary in thickness based on the health of the tree, which is often closely tied to weather events like drought or storms. In this case, in the years after large hurricanes, tree rings were smaller than in years without hurricanes. Using that knowledge and a database of tree rings from the Florida Keys, the researchers were able to figure out which years had large hurricanes going back to the year 1707.

Then they were able to push that back even further by comparing the tree rings with records of ships lost in storms in the Caribbean, dating all the way back to 1500, after Europe began exploring the Americas. The Spanish in particular kept detailed records of ships lost in storms. While ships, unlike trees, can move, before the advent of weather forecasts ships tended to go down in storms much more often than they do today. The researchers compared the shipwreck records and tree ring records and found that they matched unnervingly well.

“We’re the first to use shipwrecks to study hurricanes in the past,” lead author Valerie Trouet said. “By combining shipwreck data and tree-ring data, we are extending the Caribbean hurricane record back in time and that improves our understanding of hurricane variability.”

“We’re the first to use shipwrecks to study hurricanes in the past.”

But one piece of data jumped out in their new record. In piecing together the history, the researchers found a distinct gap in hurricanes between the years 1645 and 1715. During that time period, the years with hurricanes went down by 75 percent.

That time period directly corresponds with the Maunder Minimum, a time when sunspots were reduced dramatically.

“We didn’t go looking for the Maunder Minimum,” Trouet said. “It just popped out of the data.”

It’s an interesting observation, because there is no direct link between sunspots and hurricanes–it isn’t as though astronomers can observe 10 sunspots, and forecast an intense hurricane season. But the climate on the Earth is very dependent on the Sun, and researchers are still looking into ways that solar weather affects the weather here on Earth.

There were certainly other factors involved in the reduction of hurricanes during that time. As the authors note in the paper, the lull happened during the ‘Little Ice Age,’ a period of unusually cold temperatures in the Northern Hemisphere, and in addition to the strange solar weather, cool sea surface temperatures in the North Atlantic, El Niño–like conditions, and other climate shifts could have contributed to the lull. But having a better (longer) record of how and when hurricanes formed in the past could make forecasting future hurricanes that much easier.