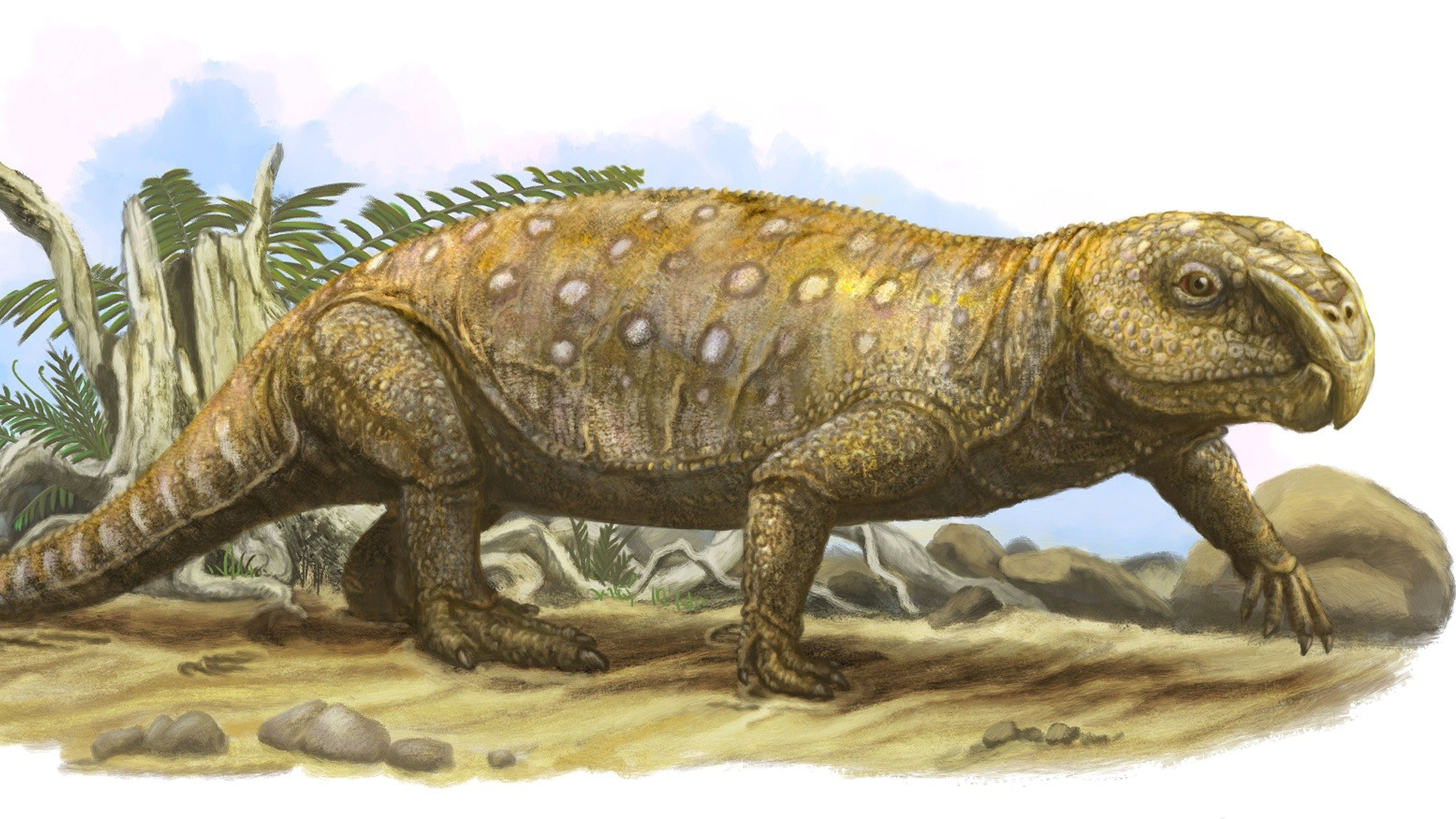

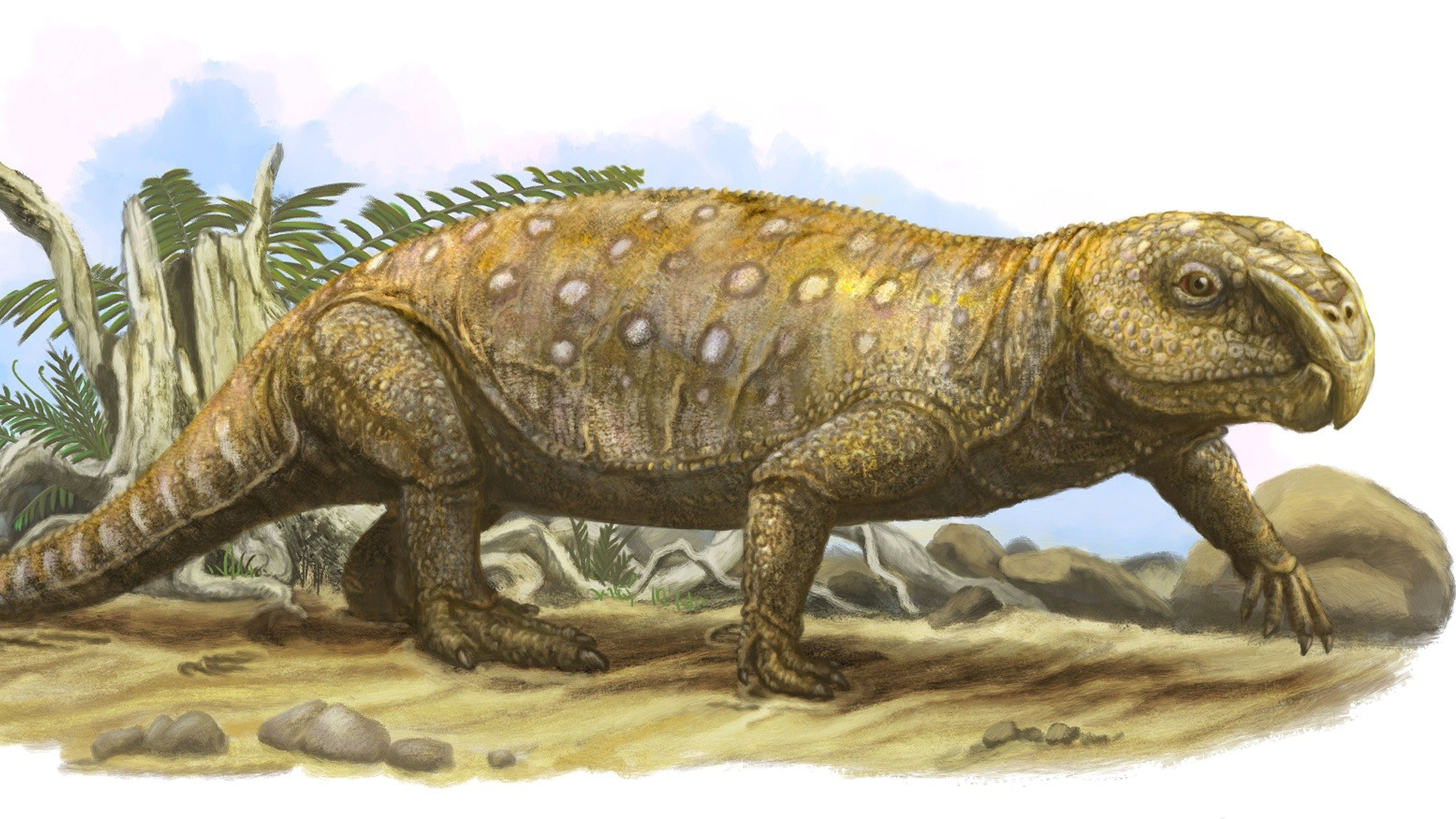

On this fossil Friday, we’d like you to meet the rhynchosaur. This ancient reptile is a distant relative of crocodiles and modern birds, roaming through present day North and South America, Europe, Africa, Madagascar, and India between 250 to 225 million years ago. It belongs to a group of roughly sheep-sized ancient reptiles that thrived during the Triassic Period. The Triassic is known for its hot climate and abundance of vegetation.

[Related: This tiger-sized, saber-toothed, rhino-skinned predator thrived before the ‘Great Dying.’]

A study published June 8 in the journal Palaeontology describes a handful of rhynchosaur specimens found in Devon in southwestern England. Researchers used CT scanning to see how their teeth wore down as the herbivores fed on leafy greens and other rough vegetation, as well as how new teeth were added towards the back tooth rows when the animals grew in size. As the vegetation took its toll on the rhynchosaur’s teeth, they likely starved to death as they aged.

“Comparing the sequence of fossils through their lifetime, we could see that as the animals aged, the area of the jaws under wear at any time moved backwards relative to the front of the skull, bringing new teeth and new bone into wear,” co-author and University of Bristol paleobiology student Thitiwoot Sethapanichsakul said in a statement. “They were clearly eating really tough food such as ferns, that wore the teeth down to the bone of the jaw, meaning that they were basically chopping their meals by a mix of teeth and bone.”

During the Triassic, rhynchosaurs were an important part of Earth’s ecosystem. Life on Earth was recovering from the greatest mass extinction in the planet’s history. During the Permian-Triassic mass extinction, or the “Great Dying,” massive volcanic eruptions triggered catastrophic climate changes that killed 80 to 90 percent of species on Earth. It paved the way for dinosaurs to dominate Earth, but was even more dramatic than the extinction event that wiped out the dinosaurs 65 million years ago.

Rhynchosaurs helped set the scene for new types of ecologies as dinosaurs became dominant, followed by the rise of the mammals.

“I first studied the rhynchosaurs years ago and I was amazed to find that in many cases they dominated their ecosystems,” co-author and University of Bristol paleontologist Mike Benton said in a statement. “If you found one fossil, you found hundreds. They were the sheep or antelopes of their day, and yet they had specialized dental systems that were apparently adapted for dealing with masses of tough plant food.”

[Related: These tiny ‘dragons’ flew through the trees of Madagascar 200 million years ago.]

The team compared examples of earlier rhynchosaurs like the ones unearthed in Devon, with later-occurring samples from Argentina and Scotland. They were able to see how their teeth developed over time, and eventually how this unique dentistry allowed the species to diversify twice. Their chompers changed in the Middle and Late Triassic.

Ultimately, another period of climate change and especially major changes in the kinds of plants available for the reptiles to eat, allowed the dinosaurs to take over and the rhynchosaurs went extinct just before the end of the Triassic period, roughly 237 to 227 million years ago.