Few things have inspired as much mythology and mystique as the moon. We’ve credited it with triggering madness, housing deities and rousing werewolves. Even after the age of Enlightenment, astronomers hyped up the moon so much, that the more we found out about it, the more unglamorous it became. By the time Popular Science came around, most astronomers were fairly certain that the moon was dead. In fact, by 1887, we declared the moon a “frozen and dried-up globe, a mere planetary skeleton, that could no more support life than the Humboldt glacier could grow roses.”

Click to launch the photo gallery.

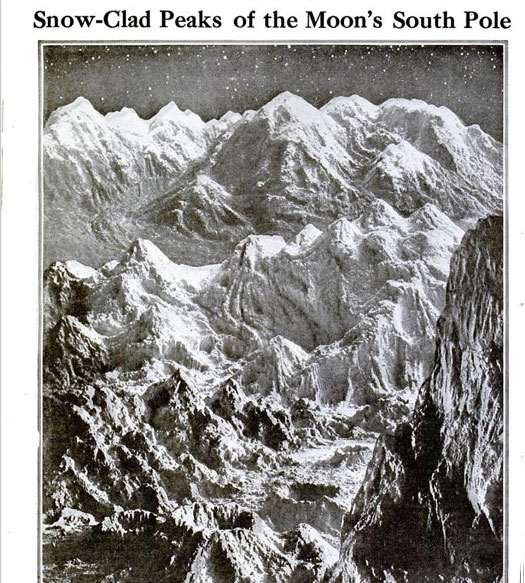

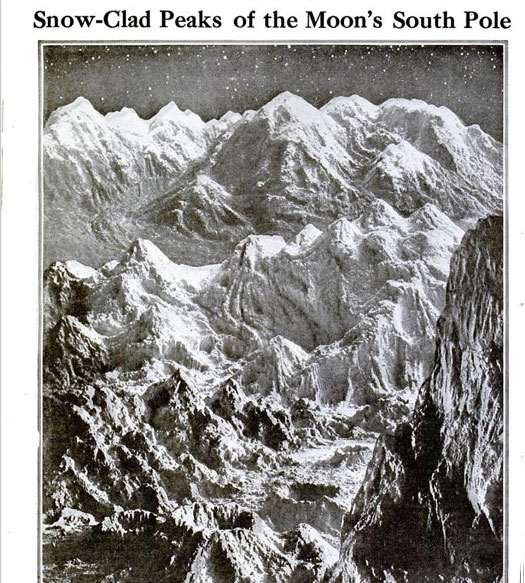

There’s only so much you can figure out about the moon with a telescope, though. Between the late 19th century and the mid-1950’s, we studied our pale satellite for answers about its origin, perhaps signs that it’d once sustained life as dynamic as ours here on Earth. Where did those craters come from? How tall are its mountains? And of course, what lies on the dark side of the Moon?

In 1917, just thirty years after we published a piece speculating that an ancient, now dead, civilization had once resided on the moon, we featured more recent findings lamenting it as little more than a desolate wasteland of volcanic debris. Two decades later, we confirmed that the moon virtually lacked an atmosphere. All the while, astronomers continued debating the origins of the moon itself. One camp believed that it’d been thrust by gravity out of the Earth’s crust, while another camp believed that the moon was the shell of an ancient, miniature sun.

If there’s one thing that remained consistent within the pre-Moon Landing era of our archives, however, it was our eagerness to send a human being up there to study the lunar landscape for himself. In 1920, Robert H. Goddard hinted at the possibility of sending a rocket to the moon and having it explode upon impact, providing people on Earth with a brilliant light show. Although people scoffed at his ideas, 40 years later, another scientist wrote about the possibility of exploding atomic bombs on the moon (as if it didn’t have enough craters, right?)

If anything, the gorgeous illustrations within our pages show that despite our increasingly desolate discoveries about the moon, the idea of it is as romantic as ever. Click through our gallery to read more about how we studied the moon before we had the technology to go there.