In August, rain fell over Greenland’s Summit Camp instead of snow for the first time on record. It’s a sign of weather to come. New research suggests rainfall will increasingly take over snowfall in the Arctic in the coming years.

As the climate crisis warms our planet’s poles, the northern ice cap is set to transform. As sea ice melts, open water and warmer air temperatures will mean more evaporation—prime conditions for a wetter Arctic. If carbon emissions are not cut, Arctic autumns could be dominated by rain rather than snow by 2060, according to the new projections, 30 years earlier than the previous estimate of 2090. A rainier Arctic could trigger further global sea level rise, the study’s authors write in their report published Tuesday in Nature Communications.

“Things that happen in the Arctic don’t specifically stay in the Arctic,” Michelle McCrystall, University of Manitoba climate scientist and lead author of the paper, told CNN. “The fact that there could be an increase in emissions from permafrost thaw or an increase in global sea level rise, it is a global problem, and it needs a global answer.”

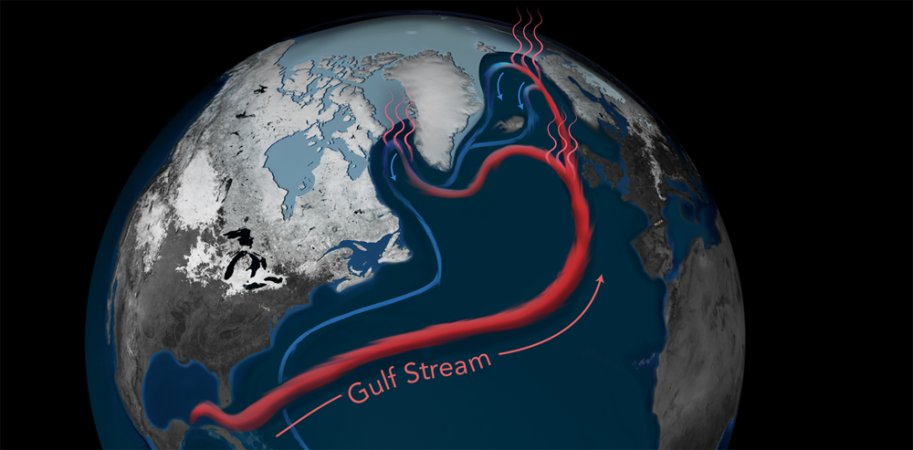

To arrive at their latest projections, McCrystall and her team analyzed data from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project by the World Climate Research Programme. The authors write that the switch-off between precipitation types could have devastating ripple effects that include global heating, starvation of wildlife, harms to Indigenous communities, altered ocean currents, and changes in marine food webs.

While it’s not surprising that the Arctic will get more rainfall, what is surprising is just how soon that transition will happen, Kent Moore, an atmospheric physicist at the University of Toronto who was not involved in the study, told CBC News. And this does not bode well for Arctic wildlife. Rain also means ice, Moore said, and for hairy animals like muskox, “that can be very, very stressful for them. They can lose heat more rapidly” because the ice sticks to their coats.

[Related: Beavers might be making the Arctic melt even faster]

Rainfall and ice melt will also exacerbate climate change in a brutal feedback loop. Much of the Arctic is tundra, a landscape of permanently frozen soil. With rainfall, “you are putting warm water into the ground that might melt the permafrost and that will have global implications, because as we know, permafrost is a really great sink of carbon and of methane,” McCrystall told The Guardian.

Weather projections are notoriously difficult to make, Marilena Oltmanns, a climate researcher with the United Kingdom’s National Oceanography Centre who was not involved in the study, told The Washington Post. “Precipitation is one of the most difficult variables for models to get right,” she added, which makes it worrying that as climate models have improved, the predicted changes appear more and more dramatic.

The new study shows that if we can limit Earth’s warming to just 1.5°C, Arctic precipitation will remain mostly snowfall. According to the research group Climate Action Tracker, which looks at countries’ current policies, the planet is on track for 2.7°C of warming. COP26 pledges could keep the temperature rise to 2.4°C of warming, but only if countries follow through.

“If we can stay within this 1.5 degree world, these changes won’t happen, or won’t happen as rapidly,” McCrystall and her team told The Washington Post. “It would be better for everybody. No two ways about it.”