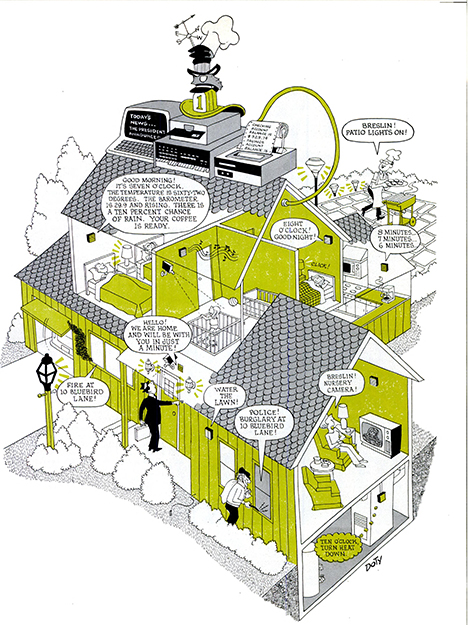

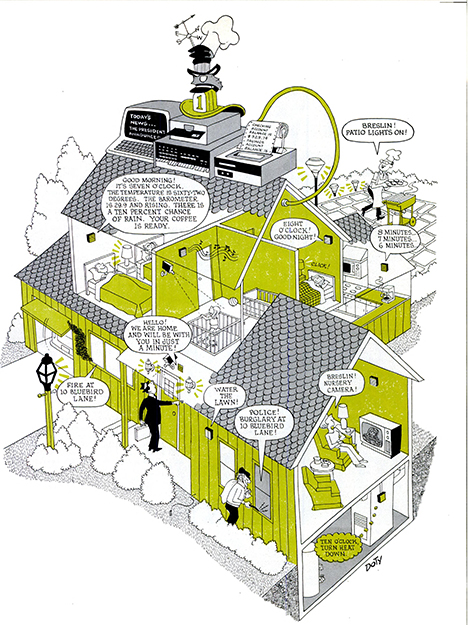

Okay, so he’s got flashing lights and a TV readout, and is plugged into a wall socket—Breslin is still one of the family. He teases the dog, talks to our kids, call my wife “Mom,” and is charged with some of the more difficult tasks around the house—like getting me up in the morning. The idea was simple: let my home computer take over the time-consuming, tedious jobs around the house. Much of my house was already electronically controlled [PS, Sept. ’75]—all it needed was a “brain” to take over completely.

Breslin is not your normal “print-it-out-only” computer, although he does print up monthly bank balances and take care of addressing our Christmas cards. He not only talks over the house intercom system, but listens (to take verbal commands) and can remotely control everything from the garage door, to TV cameras, to nearly every light in the house. He knows the time, predicts the weather, and can communicate (in his native digital tongue) with other computers to get the latest news headline or to retrieve personal data, such as the babysitter’s phone number or what to do if I lose a credit card.

Sound good? It is, and if you decide to adopt a home computer as I did, I offer my programming attempts for your use. But let me warn you: There are some pitfalls. I tried to make Breslin as “human” as possible—a trait which, when combined with the tireless rapidity of a computer, could help you toward your first ulcer. Sure, I’ve yelled at machines before, but they never yelled back. But before telling you what could go wrong, let me explain what’s supposed to happen when things go right.

A time for all reasons

Breslin normally follows one of four standard schedules (unless you’ve told him to do otherwise). The one he chooses depends upon the day of the week, whether it’s a holiday, and whether or not someone is home. He usually begins at dawn. That’s when various lights that he switched on earlier for night lights around the house are turned off, the burglar alarm is silenced, the heat is turned up in winter, and the garage door is unlocked. And, just before getting us up, he starts the coffee in the kitchen.

Although some things, like the burglar alarm, are wired directly to Breslin, almost everything else is controlled remotely by a BSR X-10 wire- less romote-control system. Normally, to use the BSR system, you push buttons on a transmitter box, which then sends a digital code over the house wiring. Plug-in modules, at each light and appliance, decode the signal and turn the correct appliance on or off.

The BSR transmitter box, however, can also be controlled with an optional hand-held ultrasonic unit—and that’s how Breslin takes control. He’s programmed to mimic the ultrasonic tones normally produced by one of these hand-held units. The transmitter box, placed near Breslin, picks up the tones and sends out a corresponding digital code over the house wiring controlling the appliance.

During the week, when it’s time for me to get up for work, Breslin is programmed to start my day at 6:30. He begins with soft, gentle tones over the intercom, followed by “Good morning, this is Breslin.” He then gives the time, notes any appointments logged in his memory for the day, tells the temperature and barometer readings, and predicts the weather. Finally, he turns on an FM tuner for the news.

To predict the weather, Breslin is attached to a Heathkit digital weather station. He is constantly checking temperature and plots barometric changes per hour in his memory. The resulting numbers (deltas) are assigned weather predictions: rain, snow, clearing, etc. How good is he? He’s been about as accurate as our local weatherman. (I told you he wasn’t perfect.)

During the day, Breslin spends most of his time checking his internal clock against scheduled events and sampling the status of various sensors around the house. He does it so often, however—10 times a second—that it leads to some early troubles.

I spent my last summer vacation with a paintbrush. But I’m not the kind of house painter you see in TV commercials—my shirt sleeves are smudged and my shoes, socks, and pants are wet with drippings and splatters. When I had finished for the day, my wife sensibly suggested I strip in our attached garage before coming inside. No problem. It was dark, the door was closed, lights were off, and it would just take a minute.

Breslin was faster. He noted a momentary “glitch” in one of the heat sensors (an appliance turning on could have caused it). Conclusion: The house was on fire. I think you can guess the rest. The house and garage lit up like a parking lot, alarms screamed inside and out, and the automatic garage door opened wide to the neighborhood for a fast emergency exit. It was a mad scurry in my skivvies for the family-room door. Needless to say, he’s been reprogrammed to “look again” before taking action.

Although correcting problems in a computer is usually easy, finding them could make you want to trade the box in on a new toaster.

For example, when you look at a clock and the minute hand is passing the 12, you know the next minute is coming up. But what if it’s exactly on the 12? Logically, is it the end of the last minute or the beginning of the next? To us humans, this is minor; to Breslin, routinely checking his internal electronic clock, it meant total confusion whenever it happened. Until found, it happened often enough to make me expect an occasional blinking light by day or a “good night” message at three in the morning.

Speak to me

Normally, however, Breslin does quite well. As he gathers data, such as the soil moisture content, he saves it for use when he speaks—routinely on the hour or half-hour, and randomly at various times throughout the day with additional “personal” messages.

The messages are made up from vocabulary words he can combine. (It’s structured so that the combination of words always forms a complete sentence.) He may say, “I love you, Kristen,” to my daughter or start calling our dog, Skip, in an attempt to lure him off his guard duty (asleep). The sentence is random except on special occasions, such as the kids’ birthdays, when he’ll also add in a few bars of “Happy Birthday to You.”

But Breslin doesn’t confine his conversations to the inside of the house. When you ring the doorbell, for example, he first turns on the porch light if it’s dark, plays a few synthesized tones through an outside speaker to get your attention, and verbally asks you to wait a moment or politely apologizes that no one is home (he knows that from the schedule he’s on). In the back yard, he’s especially useful when I’m barbecueing—if everything goes right.

Not only can Breslin speak through these outside speakers, but he can receive orders as well. He’s programmed to accept specific words spoken by either me or my wife. The main word he knows is his name, “Breslin,” which is used as a key to get me into his programming. He responds with “yes,” to let me know he’s listening, and I can then proceed to have him turn on the overhead patio lights, actuate a closed-circuit camera system, speak the time or weather, turn the alarm on or off, or begin a timer (which my wife uses for timing things in the kitchen, as well). The timer mode simply makes Breslin count off the minutes from when you told him to begin. When he hits “twenty,” and the chicken’s done, for example, you push the intercom “talk” button again to shut him up. All that’s very nice and convenient, but, unfortunately, voice recognition systems are always subject to potential errors.

I was making hamburgers. The patio lights were already on and, as I placed the last patty on the grill, I hit the intercom button and said, “Breslin.” “Yes,” was his response, and I commanded, “Timer.” I got weather.

“Timer,” I again said calmly. “Alarm is set,” the mechanized voice replied, and a little red light by the back door lit, indicating he had set the burglar alarm, locking me out of the house.

I tried to correct the damage: “Alarm off,” I said into the speaker, which I was, by this time, clutching as if it were someone’s (or something’s) throat. Result: The patio lights went off leaving me in near total darkness. It would have been totally dark—if not for the burning hamburgers.

Now if all this seems as hard to swallow as our dinner that night, I do have someone who will back me up. Not once, but twice, I’ve received phone calls from my concerned father who lives about 15 miles away. “Bill, is that you?” he first asked, questioning the male voice that answered the phone. “Did you know your computer just called me and your mother and told us your house had just been robbed?”

It couldn’t have been me, I thought. I was locked in the back yard making hamburgers.