We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn more ›

Nintendo Labo

When you’re a kid, all it takes to make a fishing pole out of cardboard is the discarded tube from some holiday wrapping paper and an active imagination fueled by an irresponsibly large bowl of sugary breakfast cereal. But yesterday, I put 45 minutes into building Nintendo’s version of the cardboard fishing pole and there was still a surprising amount of work to do.

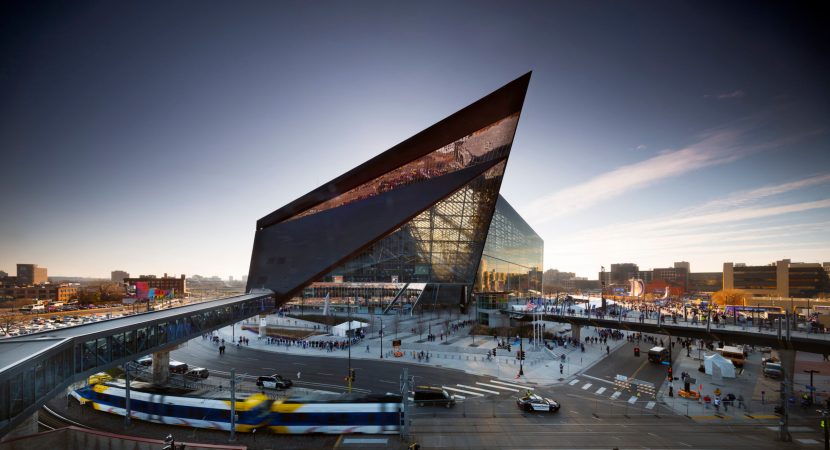

The project is part of Nintendo’s new product called Labo. It’s one of a handful of different paper craft-style objects designed to interact with dedicated Switch games. The process of building the controller is now part of the game experience, which I got to try along with some other media people yesterday. The result: It’s really fun.

What is it?

The first thing you’re going to need if you want to play with Labo is a Nintendo Switch console, which is built around a 7-inch touchscreen and a pair of motion-sensing controllers called Joy-Cons. The Labo games come with a software disc and several sheets of cardboard, each of which is perforated so you can pop-up the required pieces for each project.

Once built, the cardboard objects hold and interact with pieces of the console itself to make them interactive. For instance, the motorbike project uses a Joy-Con controller in a set of cardboard handlebars to control a game you play on the screen. The cardboard piano taps a specific spot on the touchscreen when you push a key to create a specific pitch.

The Switch is like a modular brain that powers each individual cardboard object, which Nintendo calls Toy-Cons.

When Labo launches on April 20, there will be two different options. The $70 variety kit comes with five individual projects of varying difficulty that result in five total Toy-Cons. This includes:

- RC Cars (You get enough materials to make a pair)

- Fishing Rod

- House

- Motorbike

- Piano

The other package is an $80 Robot Kit, which makes a single robot suit project that’s much more complex than the variety pack Toy-Cons and also has more flexibility when it comes to later gameplay.

The building process

Over the course of the demo, I got to build the RC cars and the fishing pole. The directions are extremely detailed, made up of slick, colorful animations, as well as 3D models of the individual pieces in which you can zoom and rotate in order to get the clearest picture of how to put the thing together. You can control the speed of the animations, but it can get a little tedious watching it trace the pre-scored line of every single fold you’re supposed to make in an animated way. Of course, I say that as an adult, but this is likely beneficial for younger kids who want to tackle the projects on their own. Also, this stretches out the time it takes to actually build the projects, which adds some value to the $70+ kits.

Nintendo Labo Assembly

The cardboard itself is very reminiscent of a pizza box—only without the grease stains. It’s extremely easy to punch out, but sturdy enough that I wasn’t afraid of annihilating the pieces while bending them into place. Durability was one of my biggest concerns going in—I’ve seen what kids can do to plastic toys, let alone cardboard ones—and I felt better after handling the actual products.

The RC cars were dead simple. Ten minutes and they were together. The fishing rod really did take nearly an hour since we weren’t rushing to get it done. Nintendo built in little surprises along the way, too. The rod has a working reel, which is cool, but it has a little tab of cardboard inside the rotating mechanism that makes a clicking noise that imitates the real thing. The rod also telescopes, which makes it feel more like an engineering project than snapping together a toy as fast as possible.

I didn’t get to build the robot suit—which is really just a backpack and helmet that will fit anyone, including kids and adults—but it’s very obviously an in-depth process to get it together. It’s made up of a backpack with four cords protruding, each of which corresponds to a player’s limb. There’s also a headset. I asked a Nintendo rep how long it’s expected to take, and while I didn’t get a concrete number (there’s a lot of variance in these things), he did tell me it was “easily a couple hours,” and I believe it.

Nintendo Labo Robot Suit

Beyond the build

The post-build playtime was really the biggest question mark about Labo and it haslingered since the announcement. If you’re going to shell out $70 or even $80 for a toy (not including the cost of the $300 console), you’re going to want more than a couple hours of Lego-style built-on-rails playing.

This was the biggest surprise for me.

Each project has unexpected things to find during the “discovery” phase of play. The RC cars, for example, have access to the Joy-Con’s built-in infrared and thermal cameras. So, you can drive around in the dark with night vision or switch over to heat vision and track your pets in the dark like the Predator.

The piano has tons of options, including “plugs” that you can insert into the cardboard housing to change the sounds and a bar on the side that slides the pitch. The house project also has an assortment of these “pop-in” gadgets, like a switch and a knob, and they change the game you play on screen, depending on which ones you pick.

In short, there’s plenty of stuff to discover.

That, to me is one of the key differentiators between Labo and other STEM toys at the moment. Typically, once the object is built, that’s when the child sets about “programming,” typically with a language like Tynker or some other visual command language. Labo, instead, still feels like a game.

The previously-mentioned Lego Boost, for example, includes games and activities that you can do with the finished products, but they feel extremely limited and get old fast. I could play with the Labo piano or the motorcycle racing game for a long time without getting bored. Even the fishing game, which feels very much like a time-wasting mini game, is oddly enchanting. I want to catch that stupid shark, which is the holy grail of this simplified fishing simulation.

These games feel like Nintendo games. And while that may not be quite as educational as a dedicated teaching toy, it’s an extremely engaging experience.

Durability

One of the most common questions about the cardboard Toy-Cons is their durability. After all, kids easily destroy many plastic toys, so what chance does a cardboard one stand? I was slightly surprised by how durable the toys felt, but perhaps only because I went in with low expectations. When our commerce editor, Billy Cadden tried on the robot suit, he pulled on the cords rather gently at first because he didn’t want to break them. Then, we heard another full-grown media person yanking on them like he was starting a lawn mower and the whole thing held up just fine. Durability will almost certainly vary between the different projects, especially when there are a lot of moving pieces like with the piano. But, we’re not talking about toilet paper tube cardboard, here.

So, should I buy it?

If you have experience with a lot of STEM toys, you’ve likely found that the majority of the fun comes from building something, then the follow up activities feel like an afterthought. Labo, on the other hand, gives a competent—and fun—building experience, but then tacks on a suite of honest-to-goodness Nintendo games.

It’s not the most educational toy out there, but we also shouldn’t expect it to be. It would be nice if it had the option to explicitly point out different engineering concepts along the way, but that could be something the company adds as it refines the process. And I don’t see any reason why the Switch couldn’t support some rudimentary coding instruction down the road, too.

The process is still on rails for the moment, but it’s easy to envision a future in which Nintendo gives kids more freedom to build objects with more flexibility and freedom. I look forward to the day I can build my own cardboard Yoshi and ride it around the house after I finally manage to fold it together.