If mankind is ever to become an interplanetary species, our outward expansion across the solar system probably can’t be fueled by NASA funding alone. Why did the first humans venture out of Africa? What made the Europeans sail into the unknown? What drove Americans to expand across the continent? Curiosity and an adventurous spirit, yes, but more importantly: resources–be they riches, food, or fertile farmland.

Similarly, resources may be the only thing that can lure us from the comforts of Earth. Mining for lunar water could make it up to 90 percent cheaper to colonize the moon. And extracting platinum and other minerals from asteroids could propel mankind to travel beyond low Earth orbit.

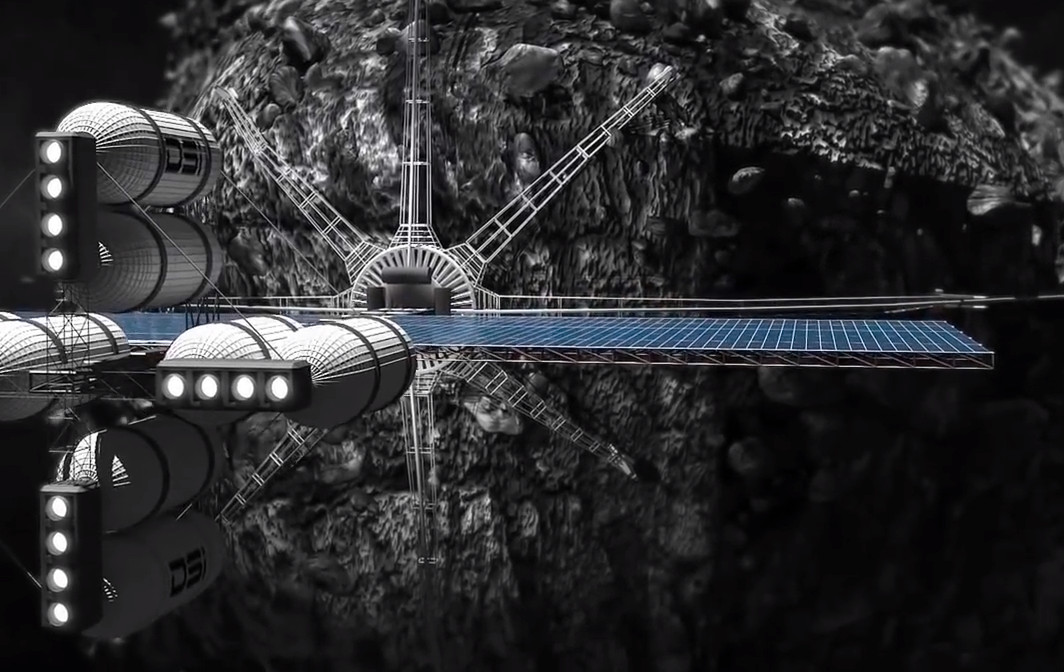

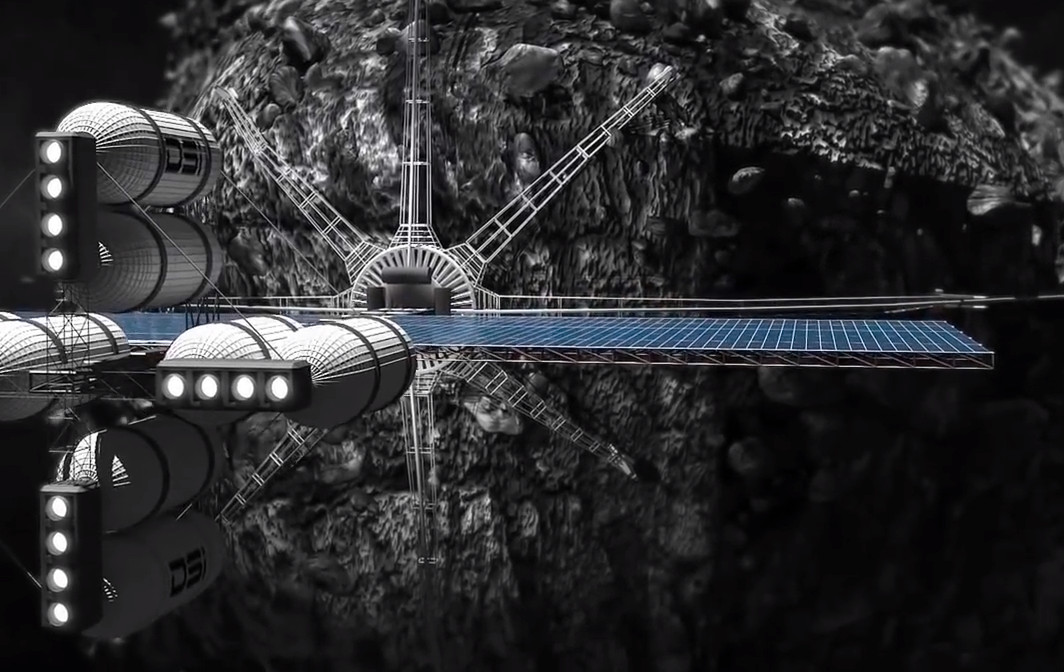

At least two companies—Planetary Resources and Deep Space Industries—are openly planning to mine asteroids. The former has already launched a simple test vehicle into low Earth orbit, with more planned.

Both companies have a long way to go before their technologies will be able to visit an asteroid, assess what valuable resources it contains, and then extract those resources and deliver them back to Earth. First the companies need to clear a major legal obstacle.

The Outer Space Treaty, which the U.S., Russia, and a number of other countries have signed, specifically states that nations can’t own territory in space. “Outer space shall be free for exploration and use by all States,” the treaty says. “Outer space is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means.”

But what does that mean for a private company?

“There is no clear-cut answer as to whether [private mining in space] is legal or not,” says Frans von der Dunk, a space law professor at the University of Nebraska. “It depends on your interpretation of certain rather broad statements in the Outer Space Treaty, and it depends on your particular interests.”

In May, the House of Representatives passed a bill that would give asteroid mining companies property rights to the minerals they extract from space. Called the Space Act of 2015, the bill now awaits the Senate’s decision.

If the decision isn’t made by the end of September or shortly thereafter, an expiring moratorium will give the Federal Aviation Administration permission to begin regulating commercial spaceflight—something conservatives have wanted to postpone so that the fledgling industry could have some time to grow.

Von der Dunk predicts the Senate will pass the bill by the end of October. After that, President Obama will have the opportunity to sign it into law or veto it.

The Space Act Of 2015

The bill (which is similar to last year’s stalled ASTEROIDS Act) says that resources extracted from asteroids and other objects in space belong to the person or company who extracts them. It also would require space mining companies to “avoid causing harmful interference in outer space,” and allows a company to sue others who cause “harmful interference” to space mining ventures.

“It’s a very succinct act,” says Von der Dunk. “That is one reason why I don’t foresee many complications.”

Nonetheless, it’s causing a bit of an uproar in the international community, says Michael Listner, lawyer and founder of the consulting firm Space Law and Policy Solutions.

International Concerns

Planetary Resources is pleased with the bill. “The SPACE Act of 2015 is a very good foundation for future asteroid resource activities,” a spokesperson told Popular Science. “If the bill passed tomorrow it would explicitly state a government position that has been implied for decades. The law would provide clarity and move this entire industry ahead very quickly.”

But not everyone is enthusiastic about it. In an article in the journal Space Policy, Fabio Tronchetti, a lawyer at the Harbin Institute of Technology in China, argues that the Space Act of 2015 would violate the Outer Space Treaty. He writes:

In essence, Tronchetti argues that if the U.S. passes this bill, it will confer rights to space companies that the U.S. doesn’t have the power to give.

“There is no clear-cut answer as to whether mining in space is legal or not.”

Tronchetti also points out that the bill’s concept of ‘harmful interference’ isn’t defined, and could potentially be used to create exclusion zones around mining operations. That would go against the nature of the treaty, whose goal was to make sure space remains the “province of all mankind,” open for exploration by everyone.

Although von der Dunk says that even though he doesn’t see anything in the current version that clearly violates international law, it could still cause concerns overseas.

“Russia and China might consider using this as another example of the economic aggression of the U.S. and going ahead of the international law,” he says.

The space mining debate probably should have started with international discussions, Tronchetti and von der Dunk agree, before going to the House and Senate.

But international consensus has been hard to come by in the past. The 1979 Moon Agreement, for example, would have limited mining in space to international governing bodies. Over the years, 16 nations have signed on to the treaty, but none of the major space-faring nations have agreed to it.

Von der Dunk says it’s too late for those discussions now. “It would take years and lead to a watered-down version. We’re probably going to go ahead with this.”

What’s The Rush?

Michael Listner has some major qualms with the bill in its current form. It requires the President to assess the international impacts of space mining and set up a regulatory structure for it within 180 days of signing the bill into law, but has no vision beyond those 180 days. “It’s a short-term bill,” says Listner. “I don’t think it goes far enough.”

For example, what is the licensing process for a company that wants to mine asteroids? Although issues such as this could be addressed in the President’s 180-day report, that report, Tronchetti writes, “might not be a sufficient step to fill in the gap resulting from a near-absolute absence of a national regulatory framework governing private mining activities on asteroids.” He goes on:

“There are just too many questions,” says Listner. “It conjures rights out of thin air, and has no supporting infrastructure.”

If the bill does get through the Senate, there’s no guarantee that President Obama will sign it into law. Although he’s supported SpaceX’s commercial spaceflight ventures, the international ramifications plus Democrats’ calls to discuss the implications of space mining in a committee could lead the President to veto this part of the bill. If that happens, Congress would need to drum up a two-thirds majority to override the veto.

Tronchetti notes that the bill has proceeded “in a rather sudden and unexpected fashion.” Despite strong opposition from Democrats, the Republican-led House pushed it through without any hearings or expert testimony.

But the bill may be more about gauging the reaction from the legal community than anything else, Listner says. “They could just be throwing mud at walls to see if anything sticks.”