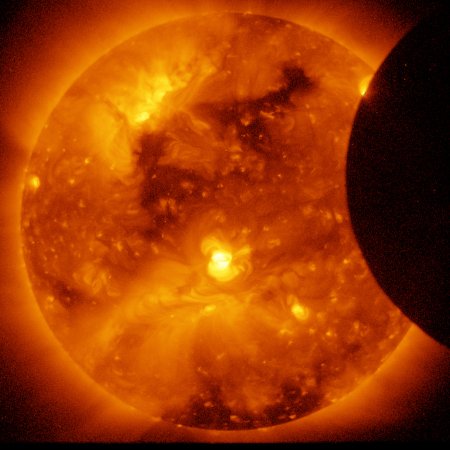

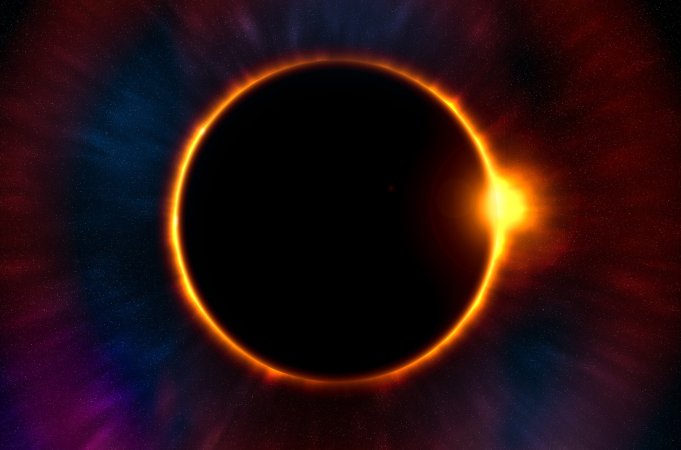

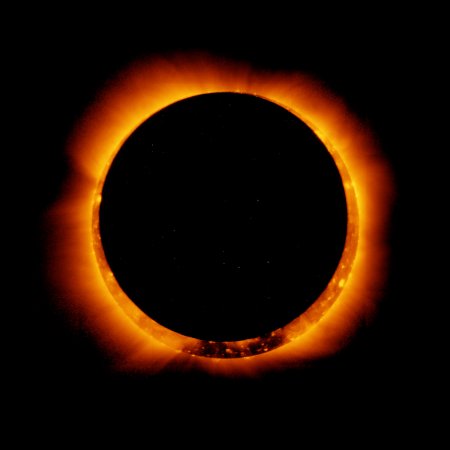

The full solar eclipse that will swoop across the United States on August 21—the first in 99 years—is exciting enough to draw up to 130 million people out to see the sun go dark. Unfortunately, this rush also poses a risk to our nation’s wildlands.

There aren’t many cities located on the eclipses’s optimal viewing path. While that’s a boon to many of the smaller communities in those areas, it also means large crowds entering forests, grasslands, and deserts, such as those found in our nation’s national parks, to camp and otherwise get their eclipse fix. This is why, last week, the Oregon Department of Forestry tweeted out this image to remind people to enjoy the scene, but to also stay vigilant about preventing wildfires.

“What that image is showing is the ten-year average for our fires and where the path of the eclipse falls,” Bobbi Doan, a public information officer for the Oregon Department of Forestry, told PopSci. “We’re just trying to raise awareness to show folks that this is where we’ve seen high fire activity in the past, and to help push prevention across the board.” The department is concerned because a single catastrophic mistake can trigger a catastrophic wildfire.

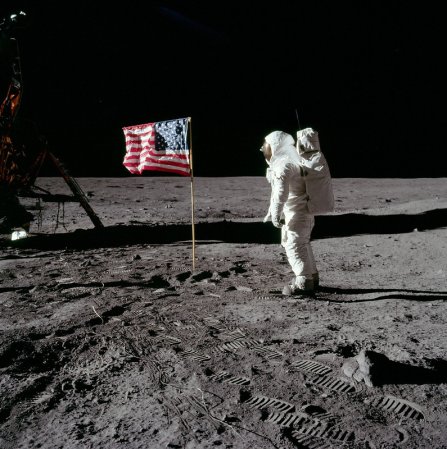

Eclipses have a long history of drawing large crowds. In 2012, authorities estimated that 30,000 people would show up for an eclipse in North Queensland, Australia; in total 60,000 people showed up. In 2015, the Faroe Islands, a country of 49,000 people and roughly 800 hotel beds, estimated that around 5,000 people would turn up to watch their eclipse; over 11,000 showed up instead. For context: That’s roughly equivalent to squeezing an extra 60 million people into the United States.

About 12 million people live along the path of the August 21 total solar eclipse, and another 88 million live within 200 miles of it. In total, 136 million people live within 300 miles of the path. More people could mean more fires. Although most forest fires are caused by lightning strikes, Oregon has seen a 12-percent increase in human-caused forest fires, which Doan says is frustrating because they’re so preventable.

The risk is compounded by the fact that many of the eclipse enthusiasts will be driving to their final viewing destinations, which can cause considerable congestion on roadways built for low volumes of vehicles. Fires are best fought when they’re still small, and heavy traffic will make it that much harder for first responders to get to—and put out—fires in a timely fashion.

These concerns are what have prompted the Oregon Department of Forestry to send out a message of situational awareness and preparedness even for those of us going to places that aren’t in a situation of heightened fire risk.

It doesn’t take much to spark a fire. If conditions are dry enough, driving over grass can be enough if the conditions are dry enough. And Oregon isn’t the only place where that’s the case these days: The high plains, including parts of Nebraska, are both located along the eclipse’s path and are unusually dry right now.

“Find out where you’re headed and definitely look for fire restrictions, because a lot of folks are going to have bans on campfire,” says Doan. “You need to know ahead of time whether or not you’ll be able to light a campfire —or even use your camp stove.“

This also means packing the right gear—a bucket, a shovel, or a fire extinguisher—so if you do light a campfire you can put it out correctly. Or if you come upon the beginnings of a fire you can quickly take action. “So, if you’re that guy who starts a fire on the side of the road,” says Doan, “you’re able to take care of it right then instead of watching it run up the hill.”

Speaking of roads, as we’ve mentioned earlier, cars start a lot of fires—either by running over onto dry grass, emitting sparks, or off-roading where they really shouldn’t be. To help prevent those fires, make sure that any road that you drive down is open to vehicle traffic. Get your car a tune up to make sure there’s nothing that could be falling off or sparking, and definitely don’t pull over onto dry grass. That droopy muffler could cause a big problem.

“When things are dry like this it really does take just a single spark and you’re that guy,” says Doan. “Nobody wants to be that guy.”

If you’re a smoker, dispose of your cigarettes properly. One flick out the window can burn down acres of wildland. And if you see someone doing the wrong thing, don’t be afraid to speak up. They’re putting your safety at risk, too.

Finally, says Doan, there are drones.

Drones are a challenge because if there’s one in the air near a wildfire, planes that help put out the fires can’t fly since crowded airspace could compromise their safety. Already the Oregon Forest Service has had fires during which they had to ground flight crews because of flying drones. Please keep your drones out of wildfires.

“’Make this event memorable for all the right reasons’ is kind of my tag line,” says Doan. “You don’t want to look back at this event and remember, ‘oh, yeah that was the year I started a wildfire.’”