Outside of pregnancy, the uterus doesn’t normally get much time in the medical spotlight. No more! Scientists are starting to explore the complicated connection between the uterus, the ovaries, and the brain to better understand how removing these organs can impact a person’s health.

Rats that had their uterus removed struggled more with working memory than rats that received other types of gynecological operations, found a study published this week in the journal Endocrinology. The scientists behind the research say this is an early step in parsing how the reproductive system—and decisions to alter that system—can influence cognition and health.

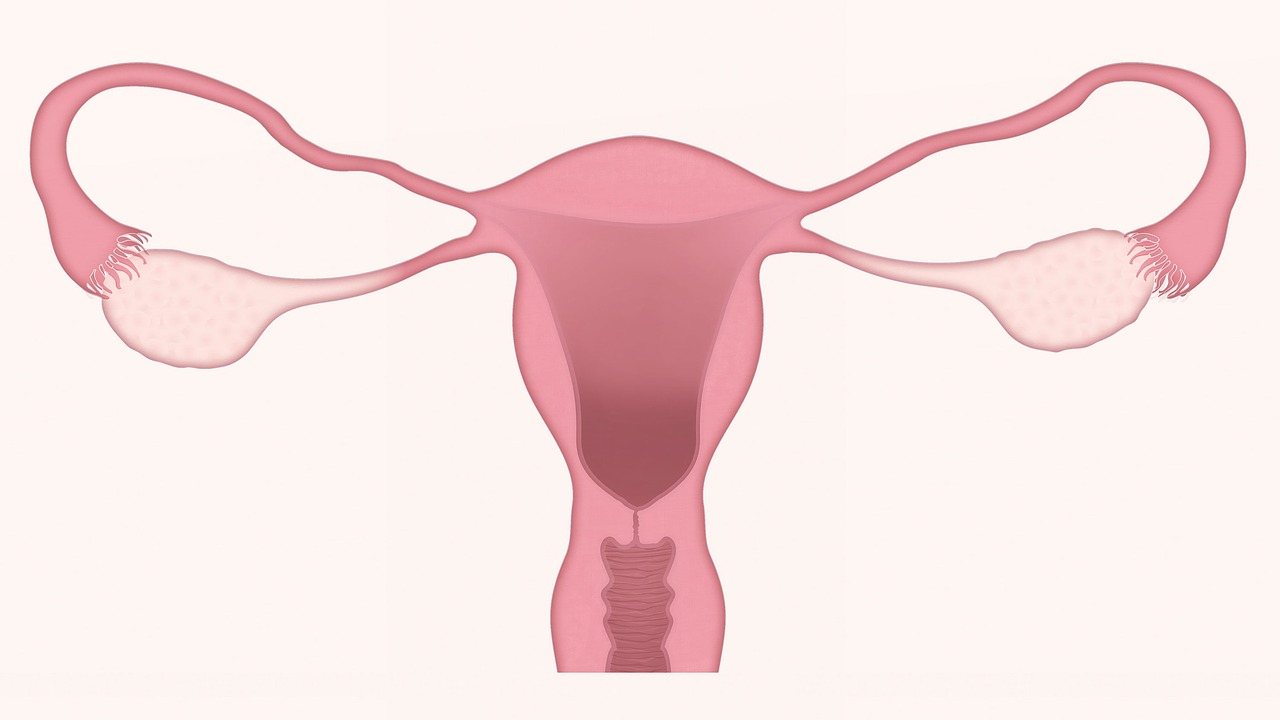

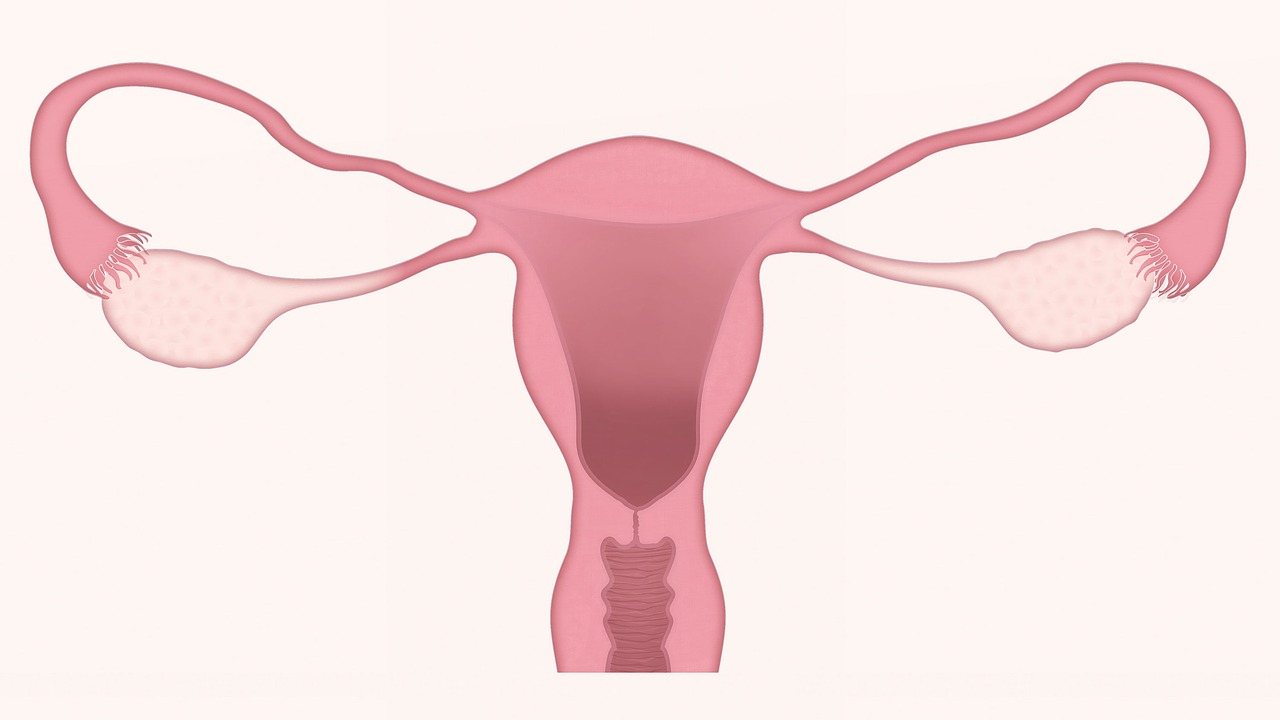

Until recently, the medical community has primarily thought of the uterus as just a “baby house,” says Donna Korol, a biologist who studies the neural mechanisms of learning and memory at Syracuse University and who was not involved in the new study. But given the organ’s role in producing and regulating hormones, this is gradually starting to change.

“Generally the dogma in the field is the non-pregnant uterus is dormant—some experts have called it ‘useless,’” says study co-author Heather Bimonte-Nelson, a behavioral neuroscientist at Arizona State University. “We believe that a woman’s reproductive organs might have value beyond their reproductive capacity, so we wanted to further evaluate the effects of the uterus.”

About one-third of women in the United States will get a hysterectomy before the age of 60, and the majority of those before the natural onset of menopause around age 50. It’s the second most common surgery for women in the United States, after cesarean section. And in about half of those surgeries, patients will have just the uterus removed, while in the other half they will have both uterus and ovaries removed. Retaining the ovaries can prevent a woman from going into sudden, early menopause after the surgery. Removing the ovaries may also be connected with increased risk for heart disease and osteoporosis.

Previous studies have found estrogens and other hormones produced by the ovaries can help protect neural structures in the brain while promoting cardiovascular, skin, bone, and urogenital health. But the uterus and ovaries are closely linked, and nerves connect the brain to both these reproductive organs. Some studies have started to look closer at this connection, evaluating the connection between hysterectomies and risk of early-onset dementia. “We’re really just starting to look at the uterus as a regulator of brain function instead of focusing on the ovary,” says Korol.

Bimonte-Nelson and Stephanie Koebele, a graduate student in Bimonte-Nelson’s lab and co-author on the paper, started the experiment by performing surgery on 60 rats. One group of rats had just their uterus removed (a hysterectomy), another group had just their ovaries removed (an oopherectomy), a third group had both uterus and ovaries removed, and a fourth and final group had surgery, but no organs removed. The researchers used procedures that mimicked the types of surgeries performed on humans.

The rats recovered from their surgery for six weeks before Koebele and Bimonte-Nelson put them to the test. The researchers assessed each rodent’s spatial and working memory using a series of mazes that forced the rats to find platforms submerged in water and navigate back to these platforms—or where these platforms used to be. Koebele and Bimonte-Nelson wanted to evaluate the rats’ ability to remember navigational clues and remember changes the researchers made to the maze over the course of the experiment.

They found that the group of rats who had only their uterus removed fared worse on the maze designed to test working memory than the others. Working memory is like short-term memory that has to be updated, explained Bimonte-Nelson. For example, just remembering a phone number is an example of short-term memory. Having to remember that phone number and then manipulate it in some way, like by adding the numbers together, requires working memory.

About two months after the surgery, the scientists reexamined the rats that still had their ovaries. They found that while the physical structure of the ovaries didn’t change, the hormone balance in the hysterectomy group and the group that didn’t have any organs removed was slightly different, indicating that removing just the uterus would cause the ovaries to produce slightly different hormones—at least for a short period of time after surgery.

Bimonte-Nelson and Koebele weren’t all that surprised that this group varied so much from the group that had both uterus and ovaries removed. The difference, Bimonte-Nelson explains, is that removing just the uterus disrupts the ovarian-uterine-neurological connection instead of removing that system completely. When the system is disrupted, the remaining organs will try to pick up the slack to return to normal, potentially leading to the hormonal changes the scientists saw in the hysterectomy group.

The short time frame—just two months after surgery—means the scientists couldn’t draw conclusions about the long-term effects of hysterectomy on cognitive function. This is also an animal model study, so the findings won’t correlate precisely with what happens in humans. Even so, the research coming out of this group represents the cutting-edge in efforts to better understand menopause, says Korol.

There’s a lot left to learn, but one thing is clear: It’s time the uterus gets some credit beyond its baby-making abilities.