Every October, when I was growing up in Massachusetts, my parents would check out the fall foliage reports and determine where we were going to drive to see the colorful leaves. And they still do. In New England, leaf peeping, as it’s called, is a billion-dollar industry and millions of people travel to the region during foliage season.

In Maine’s Acadia National Park, visitation has more than doubled in September and October since the early 1990s. Tourists book leaf peeping cruises, bus trips, and lodging packages, all scheduled to coincide with what’s traditionally been the somewhat predictable fall foliage season.

But Earth’s climate is changing. A big question is how climate change’s impacts on the timing, duration and vibrancy of fall foliage will affect the tourist season.

Pulling together all kinds of data

Untangling the relationship between climate, fall foliage and visitorship in Acadia National Park–the goal of my research–requires a variety of data, including meteorological observations, park visitor surveys, and knowledge of when fall foliage starts, peaks and ends every year.

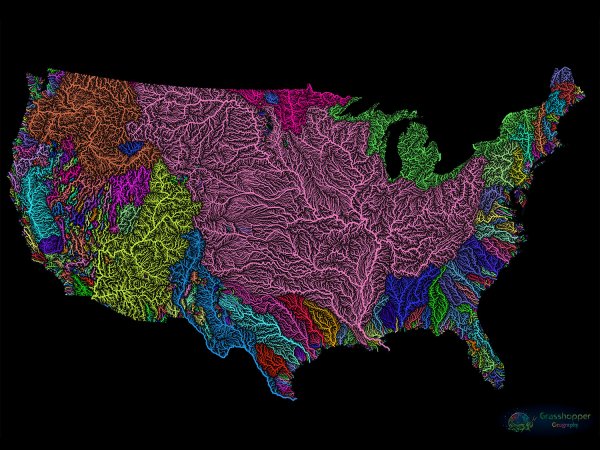

As an environmental scientist, one of the primary ways I study changes in vegetation phenology–that is, the timing of biological events like flowering, leaf out, or onset and duration of fall foliage–is through the use of satellite data. Every day, dozens of satellites circle the Earth collecting data on everything from land cover to weather to sea surface temperatures to ground water to the chemical composition of the atmosphere.

These data are crucial in teasing apart environmental changes. Scientists have used satellite data of land cover and vegetation to show that as global temperatures increase, trees are flowering earlier and earlier.

But like all technology, the farther back in time you go, the lower the quality of the data. Even worse, there isn’t any reliable satellite data over Acadia National Park before the year 2000 at all. So my team needs to get creative.

Science behind the seasonal display

Here’s what biologists do know. As summer turns to autumn, the days get shorter and colder, both of which are signals to trees to stop photosynthesizing and producing the chlorophyll that makes their leaves green. With green chlorophyll out of the picture, the orange and yellow carotenoid pigments in the leaves that are masked by all the chlorophyll production all summer have their moment to shine.

In some trees, cooler weather cues the production of a chemical called anthocyanin, which helps trees pull the nutrients from their leaves into their trunk and roots. Anthocyanin is responsible for those gorgeous red and purple leaves on trees like red maples and dogwoods.

While every tree is different, studies have found that earlier spring bud burst, warmer temperatures and a dry fall are linked to a later fall foliage season. A shorter foliage season can result from a hot summer and wet fall. Additionally, the concentration of nitrogen in the atmosphere–which humans are releasing into the atmosphere on faster time scales than nature does–affects just how red those gorgeous maples get.

The northeastern US has gotten warmer and wetter over the last century. How have these climate changes affected the timing, vibrancy and duration of fall foliage in Acadia National Park? Have tourists, in turn, changed how and when they visit the park?

Looking in new places for old foliage records

To answer this question, my team is using historical data on temperature and precipitation in Acadia National Park. What we’re missing, though, is information about when fall foliage has started and peaked, going back through the decades.

Most historical records of phenology, like those of Henry David Thoreau, are focused on the spring season. Historical documentation of fall foliage is harder to come by.

My colleagues and I are mining National Park reports and old newspapers, like this article in the Oct. 12, 1893, in the Bar Harbor Times, which is local to Acadia National Park:

“The autumn foliage on Mount Desert was never more brilliant than this year. The hills are ablaze with crimson and yellow, and the woodbine embowered cottages are resplendent with opalescent tints. But, alas ‘tis but the beetie glow in the consumptive’s cheek. A few weeks and winter’s white pail will cover all the autumn glories.”

But the records are few and far between.

We’ve found one continuous record of fall foliage since 1975, although it’s not focused on the Acadia area. Polly’s Pancake Parlor in Sugar Hill, New Hampshire has been collecting data on onset and peak of fall foliage since the mid-1970s. Interestingly, their data show that since 1975 fall foliage gets going earlier in the year, but peak fall foliage occurs later.

Maybe you have the selfies we seek

This lack of data is why we need citizen scientists to help us fill in the gaps.

With apps and programs like Nature’s Notebook, iNaturalist, BudBurst and eBird, it’s never been easier for anyone to share their observations of the world around them. Scientists have recently been trawling social media sites like Twitter, Flickr, and Instagram for data to estimate park visitation rates, map monarch butterfly and snowy owl sightings, and understand the various ways people value different landscapes.

Collecting photos from people who’ve traveled to Acadia is helping us validate the satellite data we do have. My team is able to make sure what we see in the satellite images actually represents what is happening on the ground in the park. We are so appreciative of all the photos we’ve received from people who have visited Acadia this year. And we have received a bunch, 907 to be exact, of submitted photos from the post-cellphone camera era.

That doesn’t get us back to before the advent of continuous satellite data, though. We need leaf peepers to dig deeper into their personal photo albums to help us figure out the timing of fall foliage before the year 2000.

Those earlier photos–from a time of yore when you actually had to remove film from a camera and take it to get developed–are proving much harder to come by. So far we have two data points from before 2010, one from 1987 and one from 1981.

We’re asking for your help. We know those awkward family photos of you or your parents in their 1970s bell bottoms standing in front of Acadia’s Jordan Pond exist. And we want them. If you have any old vacation photos taken in the park during the fall, scan them and send them our way.

Understanding the relationships between climate change, fall foliage and park visitorship have important implications for park management, the local economies of towns on and around Mount Desert Island, and those of us who love visiting Acadia in the fall. So leaf peep–for science.

Stephanie Spera is an assistant professor of Climate Change & Remote Sensing at the University of Richmond.

This story originally featured on The Conversation.