The remnants of Typhoon Merbok have brought high winds, storm surges, and drenching rains to the western coast of Alaska since hitting the region on Saturday. Now regarded as one of the worst storms the region has seen in decades, the flooding lifted buildings off of their foundations and left communities completely underwater. According to the National Weather Service (NWS) on Saturday, the storm was producing the highest water levels in over 50 years.

The New York Times reports that in the village of Golovin (50 miles east of Nome, the finishing line of the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race), up to a dozen of the 48 houses had been inundated with water. In Newtok, located 250 miles south of Golovin, a third of the population of about 200 sheltered in a school building. Tribal Chief Edgar Tall of Hooper Bay told Alaska Public Media News that he’s “never seen a storm like this” in the state. At least three houses in the Hooper Bay area were lifted from their foundations with 110 people sheltering at a schoolhouse as the water rose.

[Related: A super typhoon of historic proportions just cut thousands of U.S. citizens off from the world.]

According to Rick Thoman, a climate specialist at the International Arctic Research Center, many small and primarily Indigenous communities along the western Alaskan coast coast will face unique challenges as they do their best to recover from the recover from the damage before winter arrives. “All of these communities, there’s basically no road connections to any of them,” Thoman told The Washington Post. “It’s a very different setup than anywhere in the Lower 48.”

Governor Mike Dunleavy declared a disaster for impacted communities on Saturday. “The storm hitting the coastal regions of western Alaska is unprecedented,” he said in the statement, “and I want every Alaskan impacted by the storm to know that the State is working around the clock to protect Alaskans, and once the storm passes, to rebuild essential infrastructure and make our coastal communities whole again.”

By Saturday night, the governor’s office reported impacts to roads, oil storage and possibly sea walls. They are still assessing whether the storm affected water supplies and sewage systems in the state’s western towns.

Floodwaters have begun to recede, but it may be days before officials at Alaska’s Division of Homeland Security and Emergency Management (DHSEM) know the full extent of the damage. The affected areas span well over 1,000 miles of coastline. According to DHSEM public information officer Jeremy Zidek, it includes “some of the most remote areas of the United States” that are large, difficult to access, and likely to face a variety of levels of damage.

[Related: Hurricane forecasts can be confusing—here’s a helpful glossary.]

National Weather Service was able to send out warnings by at least September 15th and notify the communities in the storm’s path. “Local and tribal governments activated their emergency response plans and did what was necessary to protect their community members,” Bryan Fisher, Director of Homeland Security and Emergency Management, said in a statement. “These steps have been instrumental in preventing injury and loss of life and have minimized damage to property.”

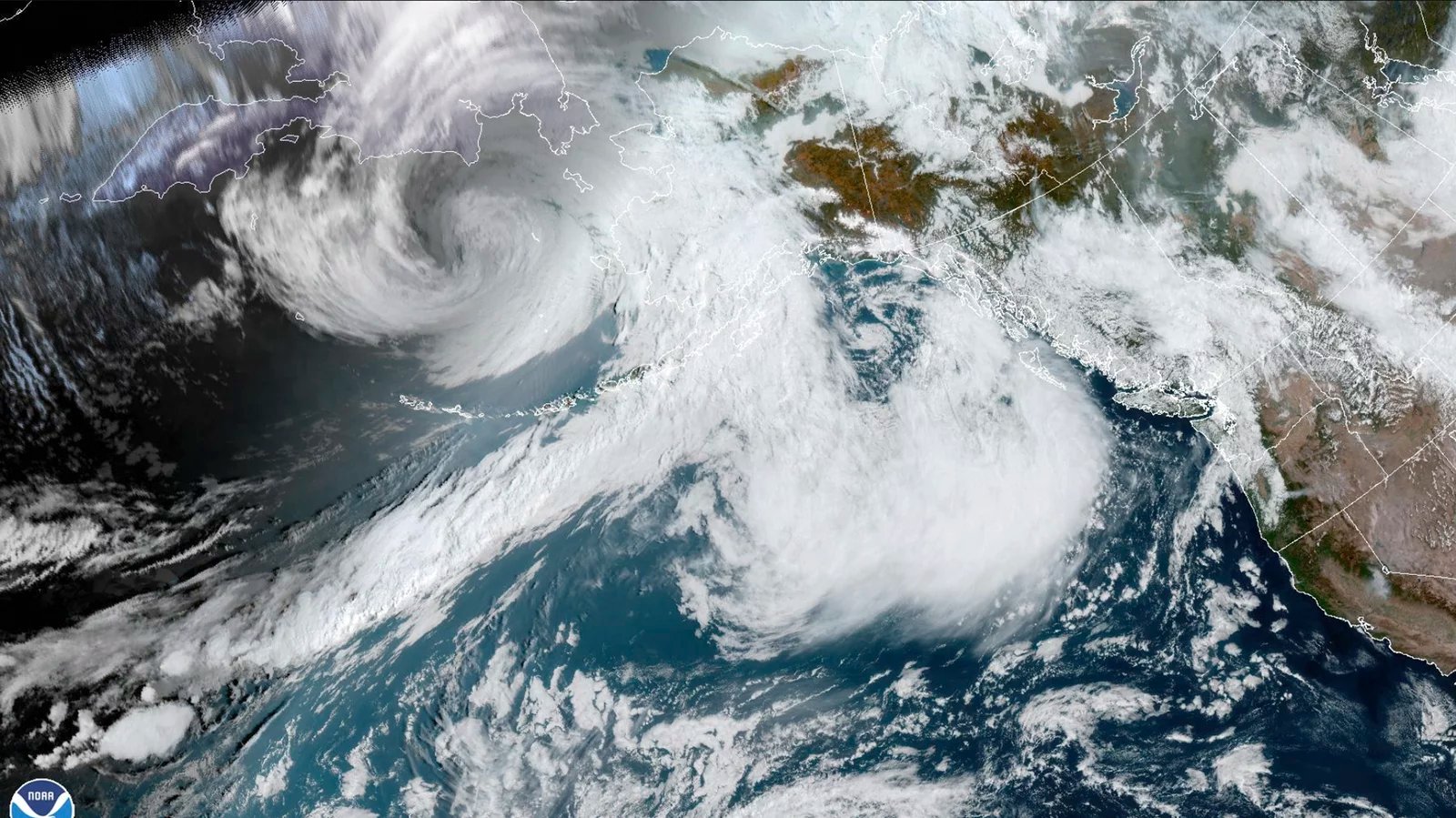

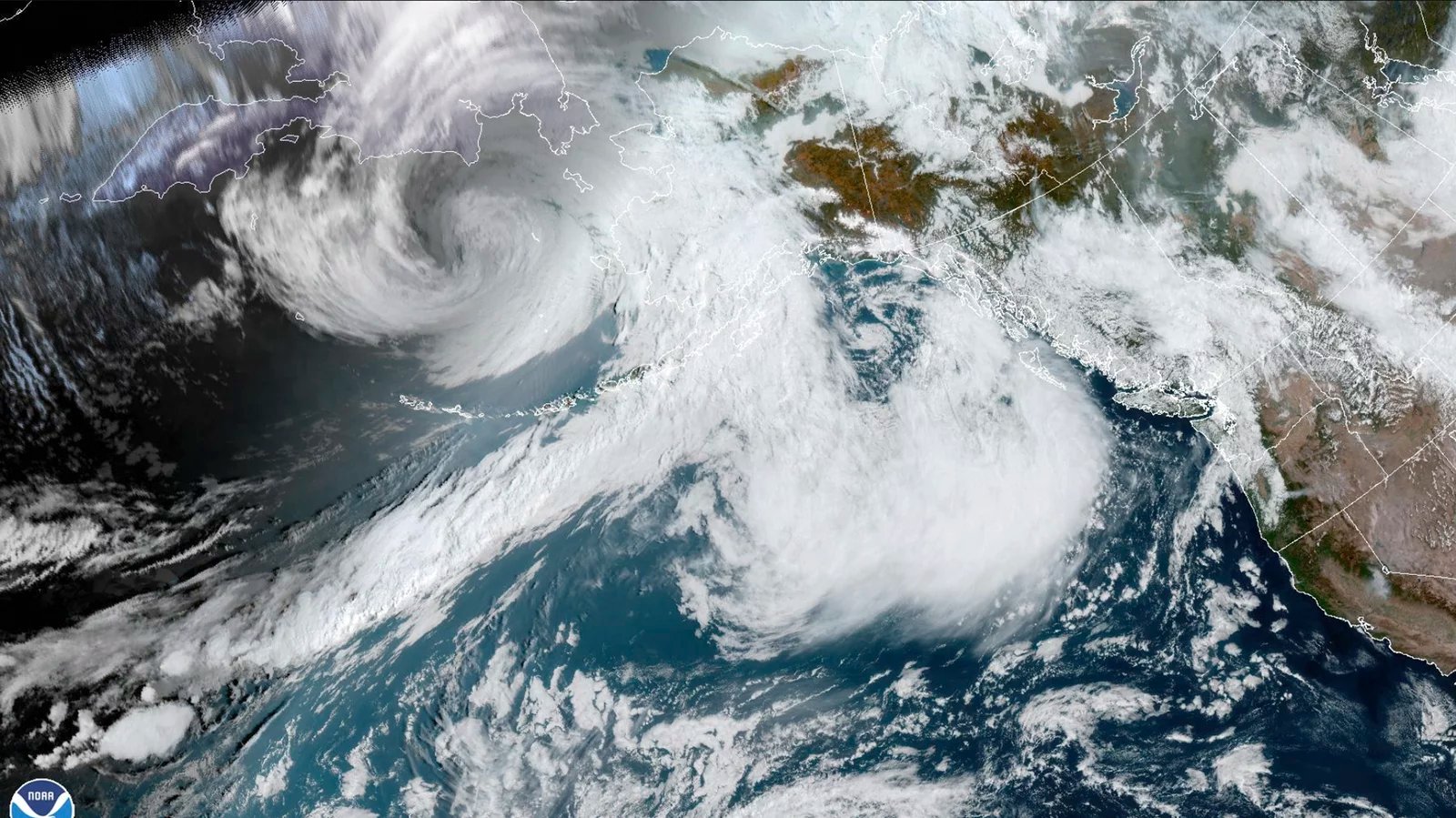

Typhoon Merbok formed over the northwestern Pacific during the second week of September and transitioned to a powerful wind and rainstorm over the Bering Sea. It transitioned into an extratropical cyclone, feeding off jet stream energy, while swirling over an area of unusually warm water again due to climate change. The waters warmed by climate change added even more energy to the storm as it surged northward into the Bering Sea. This is an unusual path for storms at this time of year, as most move into the Gulf of Alaska. The storm is considered now the most intense storm on record in the Bering Sea for September, and one of the strongest ever recorded.