A rare, half-billion-year-old fossil gives us a clue to how a bizarre marine invertebrate can possibly be related to humans. In a study published on July 6 in the journal Nature Communications, Harvard University researchers identified a prehistoric specimen in a collection at the Natural History Museum of Utah as a tunicate, or sea squirt. The preserved invertebrate, which was originally discovered in the rugged, desert-like landscape of the House Range in western Utah, can be used to understand evolution mysteries that go way back to the Cambrian explosion.

“There are essentially no tunicate fossils in the entire fossil record. They’ve got a 520- to 540-million year-long gap,” says Karma Nanglu, an invertebrate paleontologist at Harvard. “This fossil isthe first soft-tissue tunicate in, we would argue, the entire fossil record.”

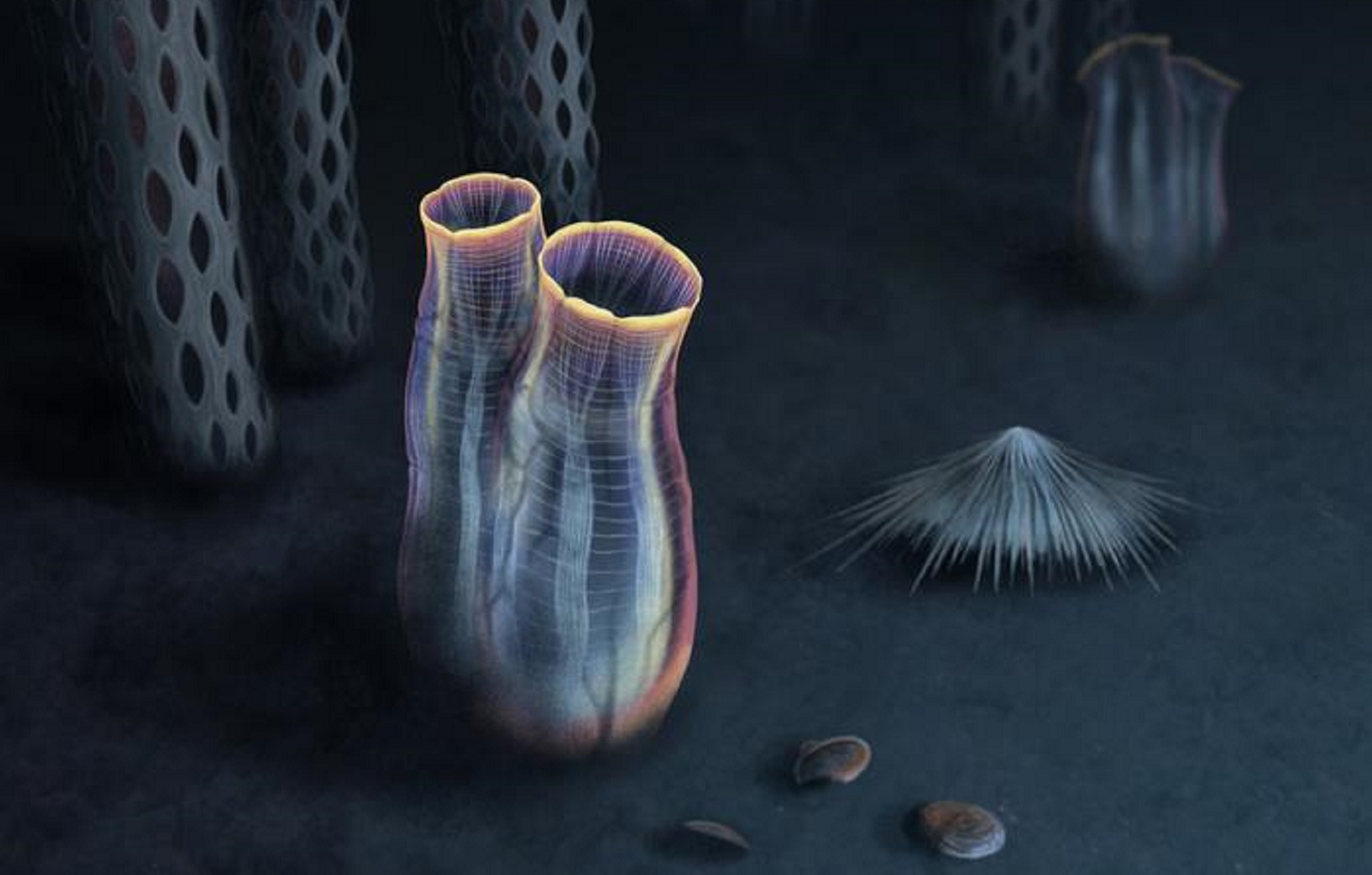

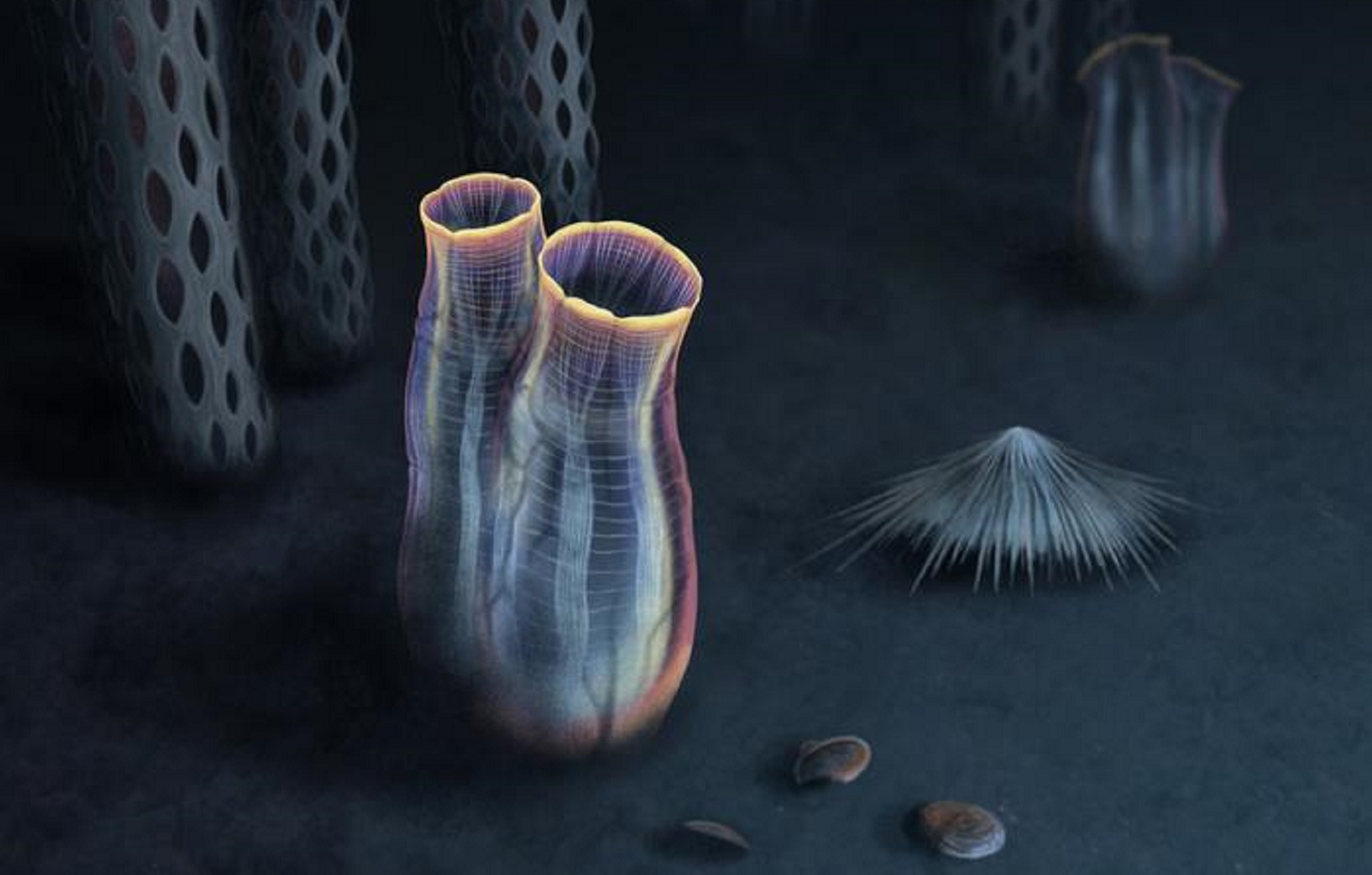

Sea squirts can be seen swaying on the ocean floor with its potato-like body and two chimney-like parts called siphons that are used to feed and expel water. While there are at least 3,000 different species today, the crayon-point-size organisms are generally unknown to people—despite being our invertebrate cousins, says Nanglu. Like humans, they belong to the chordates, which share five essential physical features during development or when fully grown. Most tunicates hatch as swimming, tadpole-like creatures, but eventually attach to the ocean floor and lead a sessile lifestyle.

[Related: Fossil trove in Wales is a 462-million-year-old world of wee sea creatures]

The soft-tissue fossil that Nanglu studied from the Natural History Museum of Utah was unidentified, but surprisingly well-preserved. After nearly 10 hours of testing, dissecting, and comparing to modern sea squirts, he was sure it was a tunicate based on its siphons, tubular body, and unique markings. He and his team named the specimen Megasiphon thylako and estimated that it was around 500 million years old, putting it near the end of the Cambrian explosion, when evolution hit record levels. With this little specimen, Nanglu says can tell researchers more information about the history of tunicate divergence and even our own.

“What the fossil shows is the assumption that tunicates did arise after the Cambrian period,” says Robert Gains, a professor at Pomona College in California who specializes in Paleozoic geology and geochemistry of the western US. “The evidence is so strong that it may place them back further, which has happened with lots of other animals as well.”

One of the big questions for tunicate origins centers on what the last common ancestor of the group looked like. This was part of what directed Nanglu to investigate the House Range specimen. Among the most prominent features on Megasiphon thylako, he says, were the dark, concentrated bands that ran from the base of the body, all the way to the tip of the siphons. The researchers describe it in the paper as “this almost pitchfork-like arrangement … they almost look like a circulatory system as found in modern tunicates.”

When comparing the fossil to present-day tunicates from other laboratories such as the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, the teams saw a similar arrangement that they interpret as muscles in the ancient species. “You can see how comparable the modern and old tunicate are,” Nanglu says.

With all the evidence laid out before him, Nanglu remained cautious about calling the specimen a tunicate at first. “We’re making a pretty substantial claim here. A group that essentially has no fossil record, and we’re saying this is the first one from that group.” Even after completing the study, he says he remains shocked and fascinated by this rare discovery.

“I can’t believe this thing was preserved. I can’t believe we have good evidence of the musculature of a thing that’s 500 million years old. I can’t believe we’re getting a look at the undersea world from half a billion years ago. So hopefully people will just be kind of amazed by just the scope of some of those components of the story.”

[Related on PopSci+: The ghosts of the dinosaurs we may never discover]

Utah, which was located near the equator during the Paleozoic era, was a hotbed for animal diversification. Sea squirts and other millions-year-old marine fossils can be found in abundance in the western part of the state. Megasiphon thylako aids understanding in not only the evolution of certain groups and species, but also the entire Marjum Formation.

“I think this discovery really shows the power of the fossil deposit that the authors are working on,” Gains says. “I think that continued exploration of that fossil deposit is going to pay big dividends into the future for our understanding of the origins of animals and in our understanding of the Cambrian period.”