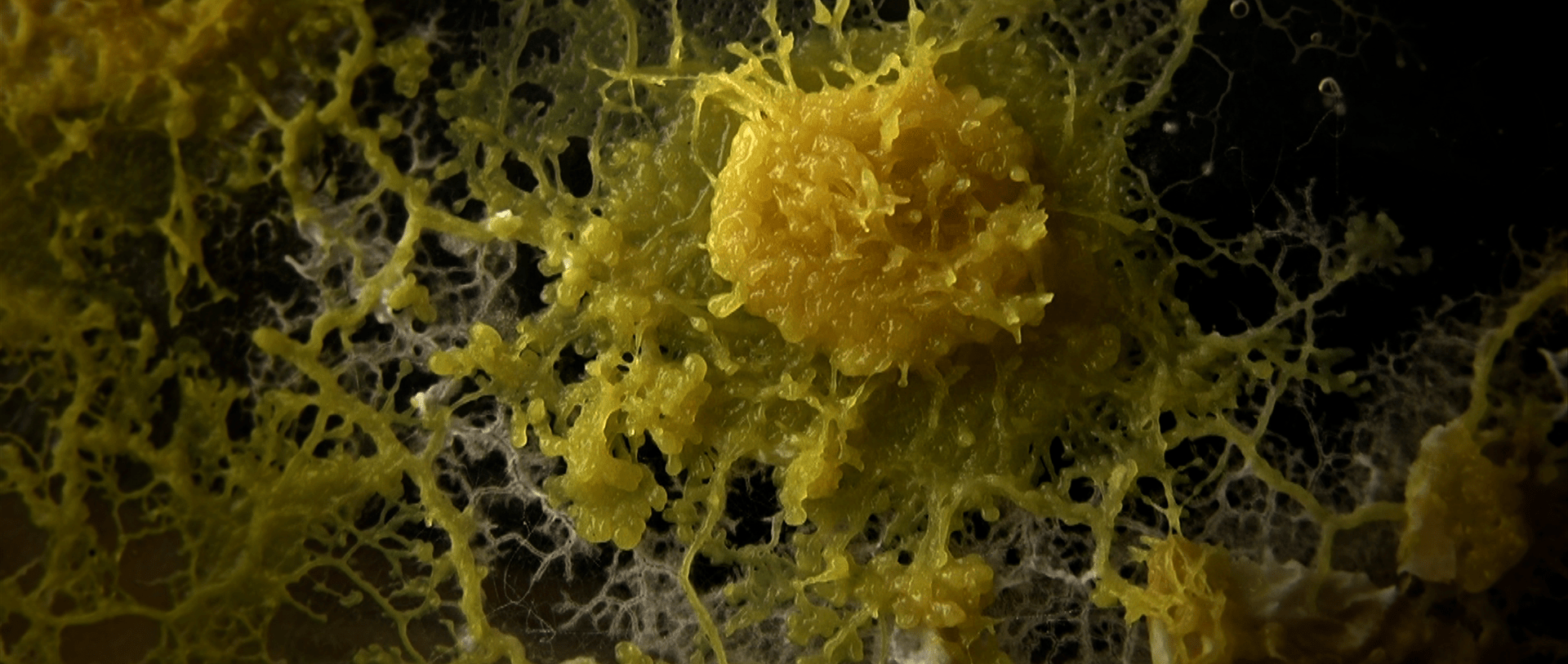

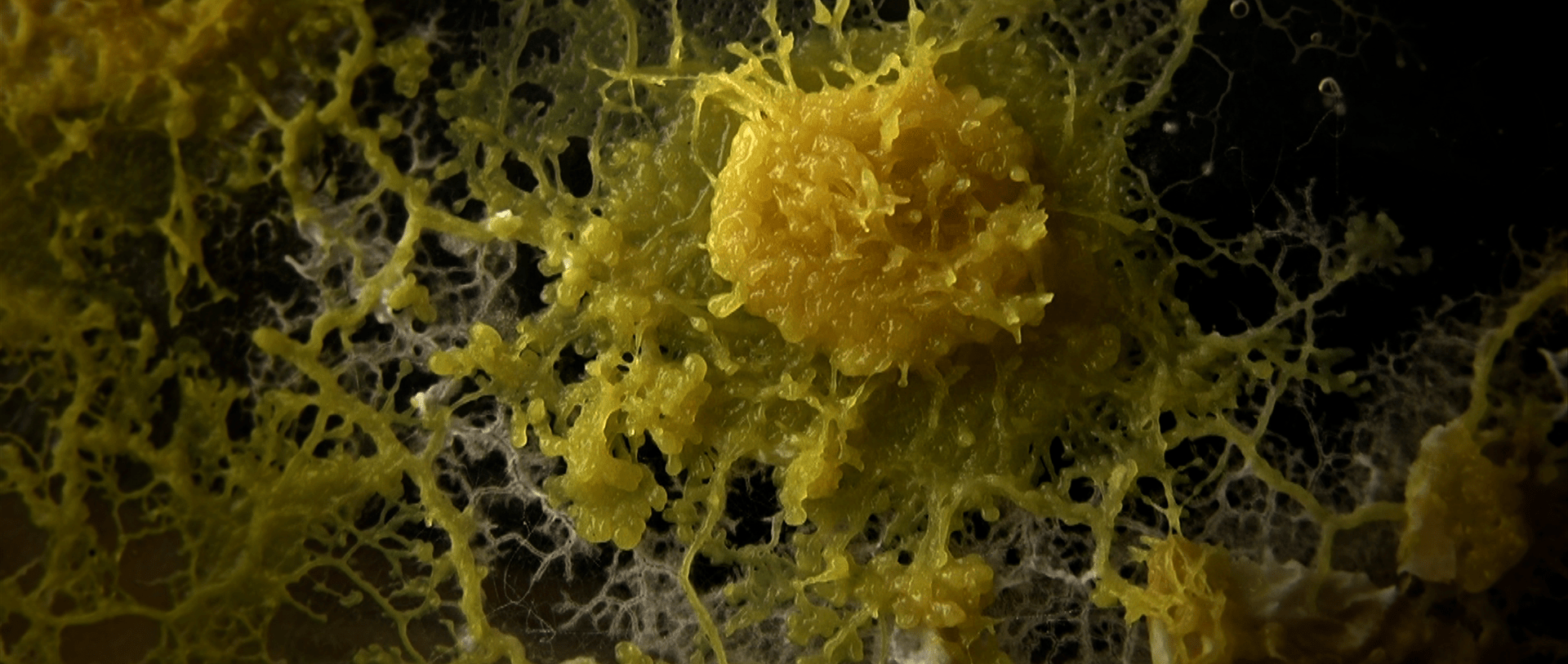

Slime mold—a living network of tendrils found on rotting wood and other plant debris—is easily one of the strangest things alive. Neither plant, nor fungus, it’s a collection of individual cells glomming together in a web-like mush that stalks the forest floor. Since German naturalist Johann Friedrich Link discovered it in 1833, slime mold—technically an amoeboid—has lured a coterie of eccentric devotees, but none have been so famous as Emperor Hirohito who reigned over Japan from 1926 to 1989.

In 1935, Hirohito wrote the first book-length study in Japanese devoted to slime mold, titled Myxomycetes of the Nasu District, containing 296 pages on the species found around the Emperor’s summer palace. At its publication it was credited to a Dr. Hirotaro Hattori, but in 1964 it came to light that the real author was Hirohito.

Today, biologists, physicists and urban planners share Hirohito’s slime mold enthusiasm mainly because it seems to display simple intelligence in solving complex navigational problems. In 2000, a team at Hokkaido University detailed an experiment where slime mold was shown to find the minimum-length between the start and end points of a maze.

In subsequent experiments, slime mold replicated Tokyo’s suburban train system. Its body morphed to form links between oat flakes representing the stations. The researchers have also shown that the slime mold possesses a simple form of temporal memory, “learning” to anticipate changes in its external environment based on previous atmospheric conditions.

In Hirohito’s case, his interest stemmed from a meeting with a famously eccentric figure named Kumagusu Minakata. Author, traveller, amateur naturalist, artist, ecological activist and philosopher, Kumagusu achieved a near cult status in Japan. He is said to have kept a succession of cats trained expressly to keep slugs away from his beloved slime mold collection growing on the grounds of his residence.

In November 1926, Minakata sent a collection of specimens to Hirotaro Hattori of Japan’s National Biological Research Institute. Three years later, Hattori appeared unwarned at the Minakata residence with an invitation to accompany none other than Emperor Hirohito on a foraging excursion on the island of Kashima.

The Emperor composed a poem about the trip, which is inscribed on the monument at the Kumagusu Museum overlooking the island:

Thus a burgeoning relationship with slime mold was memorialized.

Jasper Sharp is the co-director, with Tim Grabham, of the documentary The Creeping Garden, now available on iTunes and Vudu in North America, and the author of the companion book The Creeping Garden: Irrational Encounters with Plasmodial Slime Moulds.