Every year I burn down my backyard. Not because I have an unhealthy fascination with fire (which I do), but because my backyard is native prairie. It needs regular burning to maintain the ecosystem. Sometimes I witness fire whirls—spinning columns of flame that last a few seconds and reach 30 to 40 feet into the air. But those are nothing compared to what much bigger backyards can create: fire tornadoes.

Tornadoes are like upside-down drains. Water flowing down a sink spins as centrifugal force interacts with gravity. Similarly, when a column of warm air rises through cooler air, it can form a vortex. If that rising air contains fire, you get a fire whirl or, in extreme cases, a fire tornado—flaring monsters that can reach nearly a mile high and swirl flames faster than 200 mph.

I’ve photographed a fire whirl only once, and I hope I never see a fire tornado. I probably won’t. The only one ever conclusively documented occurred in 2003, after wildfires erupted near Canberra, Australia. Even so, scientists couldn’t confirm what leveled more than 500 homes until they reanalyzed photos of the damage in 2012.

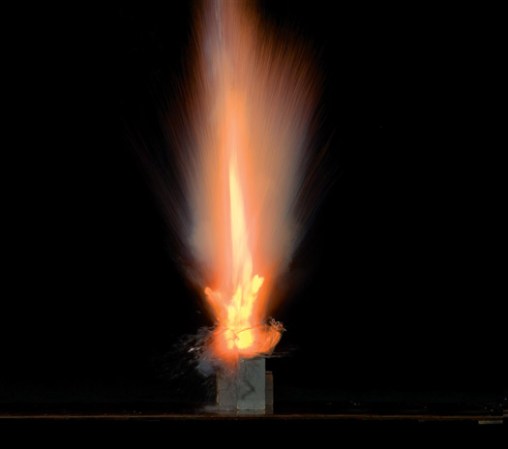

I decided to create my own tabletop fire tornado with USB fans and propane gas. I hooked the fans around a turkey-fryer ring, turned them on, and lowered the fryer’s propane burner into the breeze. It was cheating, as updrafts power the vortex in a real fire tornado, but it still looked cool as the flames compressed into a two-foot-tall twister. (Box fans around a bonfire can create much bigger artificial fire tornadoes.)

By the way, it’s myth that water drains only counterclockwise north of the equator. Fire whirls, like draining water, are too small for the Earth’s rotation to affect them (unlike huge hurricanes). Not that this fact would help if you’re ever caught in one.

WARNING: Play with fire and you’ll get burned. Propane gas flowing into swirling air is an excellent way to test this theory.