Most people associate the Jurassic Period with depictions of feathered monsters gallivanting across the surface of Earth, establishing their claim as the dominant creatures of the planet. (And perhaps also Jeff Goldblum’s finest, most shirtless onscreen performance.) But we ought not to forget that the marine world was teeming with its own gargantuan beasts at the time. A 180 million-year-old fossil has led scientists to identify a new species of a marine crocodile possessing a tail fin not unlike modern-day dolphins. The discovery, reported Thursday in the journal PeerJ, ostensibly fills a missing link in the crocodile family’s evolutionary tree, reconciling a gap where they branched out and either continued to evolve into bony-armored creatures with limbs made for walking, or returned to the water to develop flippers and tail fins.

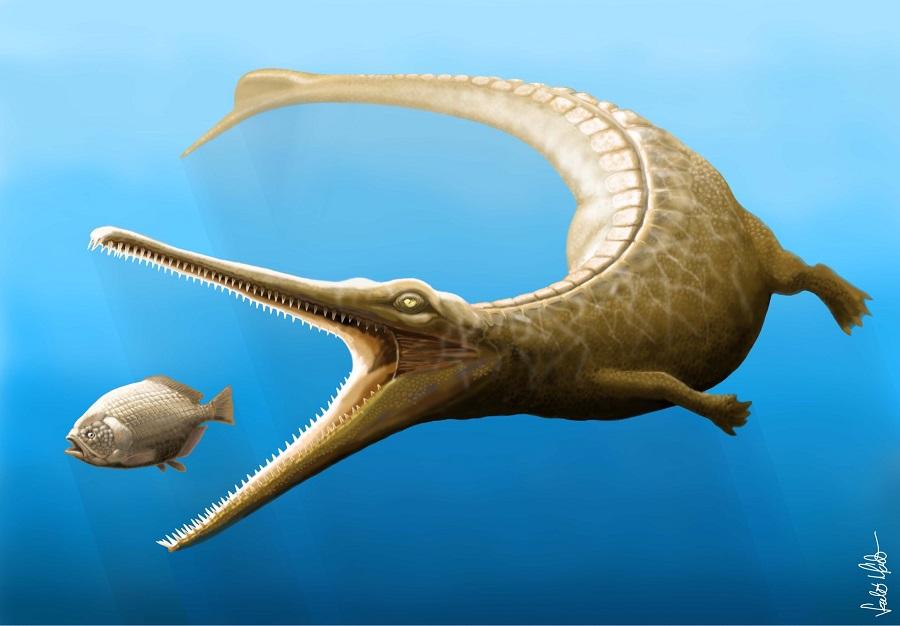

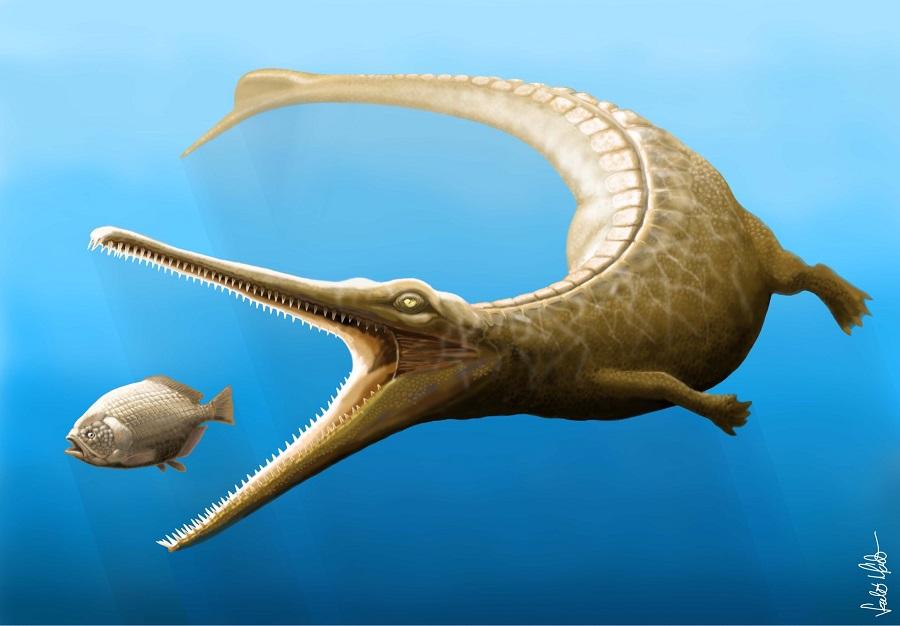

A Hungarian collector named Attila Fitos first found the fossil in question in the Gerecse Mountains in 1996, and it’s sat in the Hungarian Natural History Museum in Budapest ever since. The research team decided to name the new species preserved in that fossil Magyarosuchus fitosi, in Fitos’s honor. That animal turns out to be an almost 16-foot long behemoth with an incredibly large, pointed snout made for snatching prey, a tail fin to help it swim, and body armor more closely associated with terrestrial reptiles. It’s thought to have been one of the biggest coastal predators of its time.

The specimen, explains Mark Young, a paleontologist with the University of Edinburgh and a coauthor of the new study, was previously classified as a teleosaurid in the genus Steneosaurus. The group spearheading the new study decided to conduct a more thorough examination of each bone combined with a detailed phylogenetic analysis, where scientists infer evolutionary links between related creatures based on similarities in their physical form. This close read of the bits of bone led to the discovery of a peculiar vertebra that forms part of the tail fin—one that hadn’t been identified before.

It was this vertebra that led to a reclassification of the specimen as metriorhynchoid: Jurassic to Early Cretaceous-era crocs that eventually ditched their bony skins and evolved into dolphin- and killer whale-like animals with flippers, tail fins, and huge salt glands in the skull.

“Only metriorhynchoids evolved a tail fin,” says Young. “No other group of crocodilians did. Magyarosuchus fitosi is the oldest species in this lineage known to have had a tail fin. What’s interesting is that it had a fully developed set of bony armor along its back and on its underside, which the later forms lost. It also has different dimensions of limb bones, so it’s unlikely to have had flippers. This suggests that the tail fin evolved before flippers appeared, and before the bony armor was lost.”

According to Andrea Cau, a vertebrate paleontologist and blogger based at the Giovanni Capellini Geological Museum in Italy who was not involved with the study, the discovery of fitosi doesn’t just help researchers reconstruct how these types of reptiles adapted to a fully-marine lifestyle. It also provides a better illustration of the geological history of metriorhynchoids. “The fossil record from the Eastern Europe is much less well-known than it is in other areas, like Western Europe, which is the best documented region for this extinct kind of crocodiles,” Cau says. The new findings help illustrate how much the diversity of crocodyliforms in this era fanned out.

Whether on the ground or in the water, Magyarosuchus fitosi looks like a it made for a intimidating predator to stumble upon.