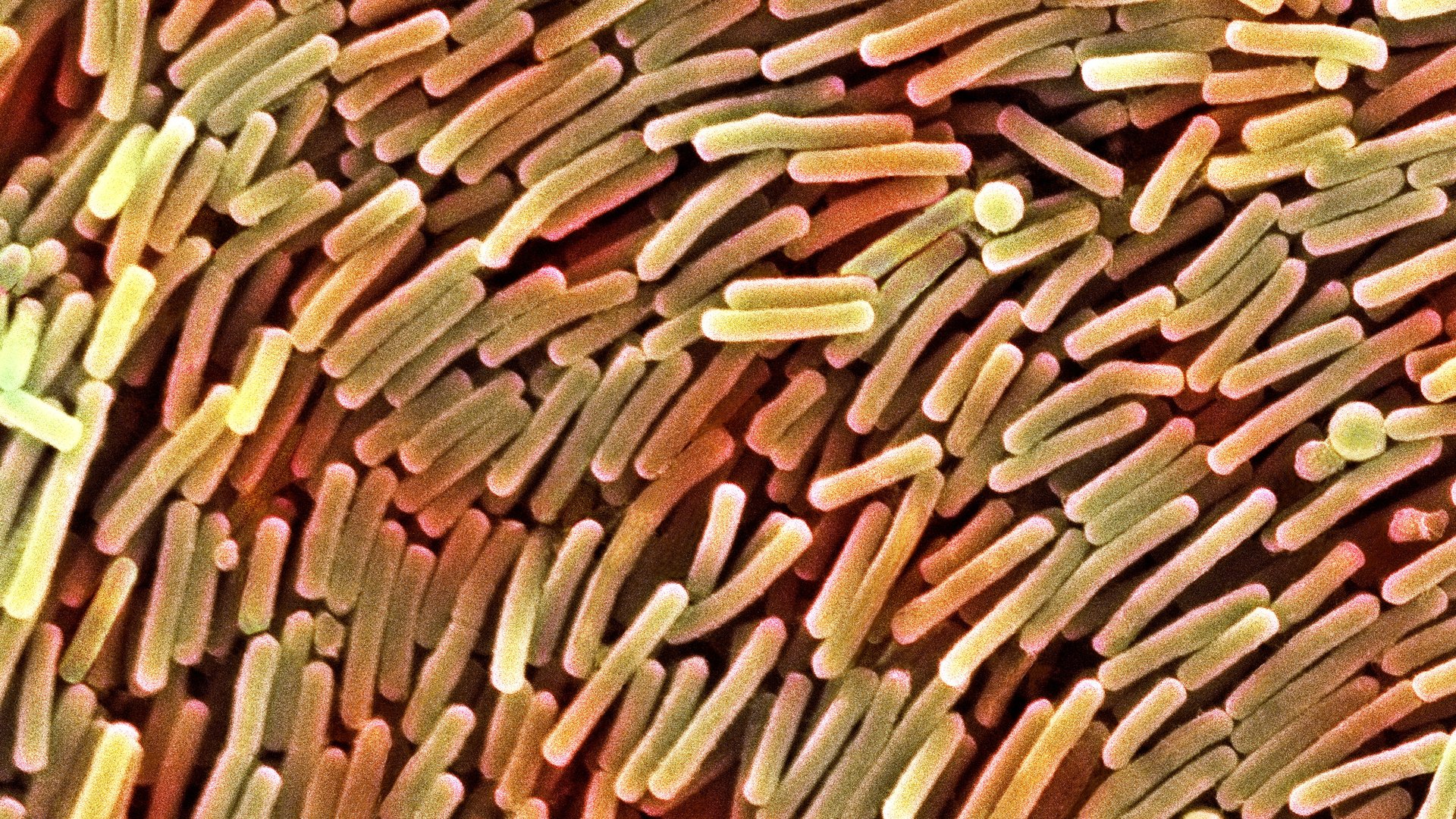

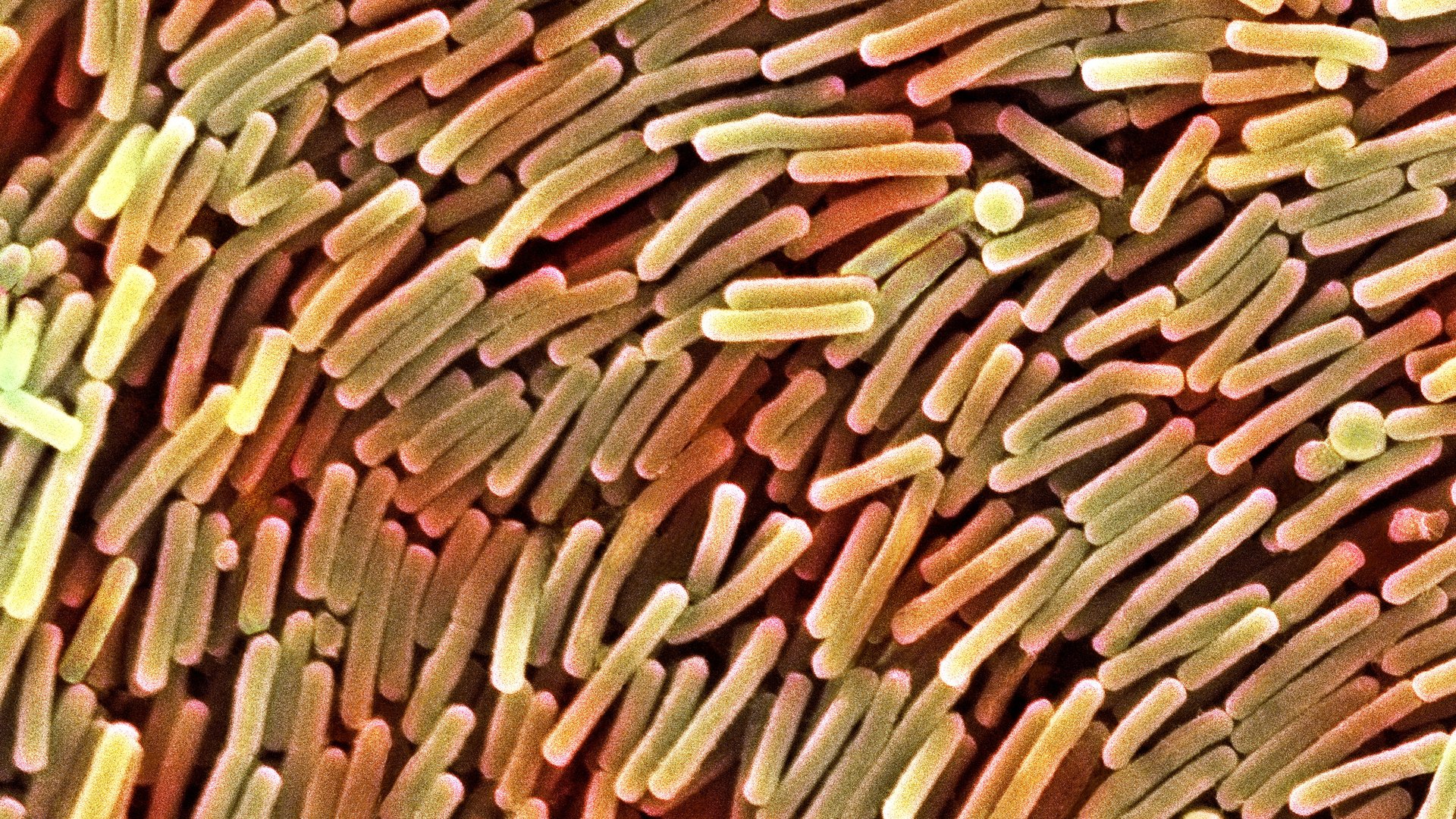

When Clostridium difficile was discovered in 1935, it was considered to be an occasional pathogen of humans. Yet, in 2005, that changed with a rampant outbreak in Canada that killed more than fifteen percent of its victims. The bacterium spread worldwide and in 2011, was responsible for more than a half a million infections and approximately 29,000 deaths in a single year.

Despite the numbers, for the most part, the occurrence of C. difficile infection has been isolated to one single environment – the hospital. Yet other areas, such as long-term care facilities, may also be burdened with this pathogen. But even in the community, people may become infected. According to models used to represent the United States, the rate of transmission is estimated to be about 0.1%.

Despite this low number of potential risk, the results show this bacterial species is out in the community and may be living, if not thriving in secret. Yet, determining the actual number of people with C. difficile can be difficult. After all, this pathogen is found in the most unpleasant of human samples, fecal matter. This means the majority of studies have focused on people already visiting healthcare facilities. Moreover, these cases are usually suffering from symptoms.

But now there may be an answer as to how common this potential pathogen is in the general community. Last week, a group of Chinese researchers published a study examining the prevalence of this bacterium in the healthy population. The results suggest the bacterium may be much more common than anyone realized. Moreover, the data suggest the most likely carriers are the ones we suspected the least.

The team focused on 3,699 healthy Chinese individuals over the course of a single year, September 2013 to September 2014. They collected fecal samples from only healthy individuals. If people were exhibiting symptoms of diarrhea or gastrointestinal infection, they were excluded. Anyone who might have been on an antibiotic was also excluded. This ensured the statistics focused solely on those who had no medical issues.

The team went one step further in their analysis to ensure they could gain even more insight. They collected information on the age of the individual. Samples were then separated based on the person’s age. While the team expected to see a difference in the rate of carriage, they expected to see a higher percentage in older individuals as they are the most common sufferers of illness.

Once the samples were collected, the team isolated the bacteria and then grew it in culture. This allowed them to be absolutely sure the data was based on the presence of living bacteria rather than simply the identification of bacterial genetic material. From an epidemiological standpoint, this step was a must as the isolation of DNA or RNA is simply not enough to confirm presence.

After confirming they had a C. difficile positive culture, the team then went on to examine the bacterium at the genetic level. This would give them the exact strain of the bacterium and provide some perspective on possible routes of transmission. They also looked for any signs of the toxins associated with illness. None of these individuals was considered to be ill, suggesting the person was a carrier with the potential to become infected upon use of an antibiotic or, worse, infect someone else inadvertently.

The final step in the testing was to identify antibiotic resistance. The phenomenon was long known to be a significant problem with this bacterium in healthcare. The researchers wanted to see if this was also the case in the community.

When the results came back, the data revealed the bacterium was quite prevalent, particularly in children. The highest rate was in infants with a quarter of those under one year of age carrying the bacterium. For children, the rate was on average 13.6%. As the age increased, the prevalence decreased. In healthy adults, only 5.5% on average carried the bacterium.

While the rate of carriage was unexpected, the presence of toxins made the data more worrisome. In infants, almost 20% of the isolates had the toxin-forming genes. In children and adults, that number skyrocketed to 65%. None of them were ill but all had the potential to fall victim to the infection or, worse, transfer it to someone more susceptible.

There was one bright side to the data. Most of the antibiotics were effective against the bacterium. However, almost all the isolates were resistant to ciprofloxacin, the one-time antibiotic of choice against infection. This suggested the rampant spread of antibiotic resistance was not limited to the healthcare facility and instead was running wild in the community.

The results of the study clearly show healthy individuals may be able to carry C. difficile without infection. This poses an increased risk to anyone who might be susceptible, such as the elderly and those on antibiotics. The data also reveals how the bacterium may be spreading in the community through poor hygiene.

But there is another more troubling concern. Despite the lack of any symptoms in these individuals, in the event an antibiotic prescription is warranted, those carrying the bacterium may be at a high risk for infection. The authors did not call for screening of patients prior to administration of antibiotic prescriptions. Yet, in light of the continuing rise of this bacterium, there may be a reason to investigate whether this protocol may be useful in the future, if only to reduce the likelihood of infection.