Every January, fat’s in the crosshairs of health columnists, fitness magazines, and desperate Americans. This year, PopSci looks at the macronutrient beyond its most negative associations. What’s fat good for? How do we get it to go where we want it to? Where does it wander when it’s lost? This, my friends, is Fat Month.

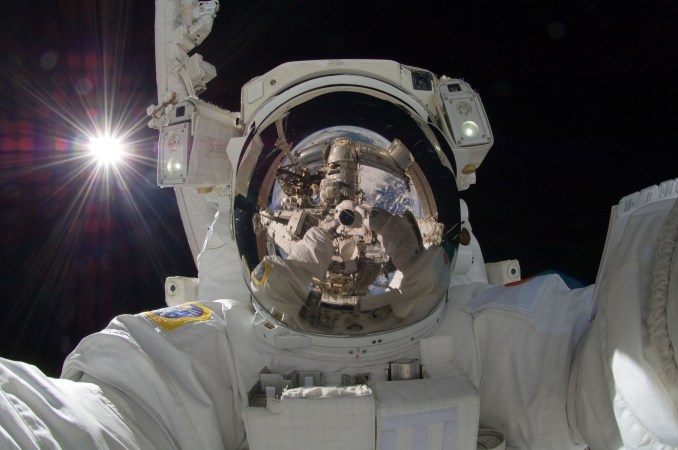

The International Space Station is a massive orbiting science project, where technologies and ideas are tested in microgravity. In the huge structure free-falling around Earth astronauts grow lettuce, test 3D printers, and explore augmented reality (in between running marathons and otherwise entertaining us all). But the astronauts themselves aren’t just scientists or engineers. In many ways they’re also test subjects for researchers here on the ground, who are eager to learn more about what happens to bodies in space.

And since it’s fat month, we were curious: what do we know about how fat acts inside an astronaut?

If there’s anyone who would have an answer for us, it’s Dr. Scott Smith, who leads NASA’s nutritional biochemistry lab. We asked him what the current research showed about how the human body processes fat in space.

“The short answer is, we don’t know much about that,” Smith says. He explains that NASA has constraints when it comes to what they decide to study, limits in both time and their subjects, so the people who prioritize nutritional studies tend to focus on high-risk aspects of nutrition.

And fat doesn’t cut it. “From an observational point of view, nothing has jumped up that gives us great concern that lipid metabolism has changed during flight,” Smith says. In other words, they haven’t seen any indication that humans process fat particularly quicker (or slower) while in space. It’s a question they’ll keep on the back burner while they attend to more pressing concerns.

Like why astronauts aren’t eating enough food, for example.

“As odd as it sounds, that’s one of the bigger challenges we have; getting crews to eat enough calories to maintain body weight,” Smith says. Weight maintenance while in space has been a challenge for astronauts for decades, and in fact used to be considered an unavoidable side-effect.

“If I go back about five years ago, many people would say that everybody loses weight in flight, and that’s just something we have to get used to. I refused to accept that then, and now we’re at a point where we’ve had a number of crew members who have maintained weight, who’ve eaten well, who frankly have come back in better shape because of it,” Smith says.

Keeping up body weight requires plenty of serious exercise six days a week on the ISS, working muscles that would otherwise languish in low gravity, but it also means cajoling astronauts to eat more food.

Astronauts used to fill out questionnaires once a week detailing their food intake. Now, thanks to an iPad app that prompts ISS residents to record every morsel of food they ingest, Smith can see the crew’s diet at all times. He knows how many calories they’re eating, as well as much protein, potassium, sodium, calcium, carbs, fat, and water they’re putting into their system.

And that’s helped Smith to notice a pattern among the astronauts who drop pounds, at least anecdotally: they don’t believe they have a problem. “They say, ‘look, I feel fine, I’m eating as much as I want to eat,'” Smith recalls. Meanwhile, he can see their body mass dropping.

What exactly is going on is still a matter for future studies, but Smith has some ideas.

“I think it’s that food doesn’t settle the same way it does on Earth, so that the stretching of your stomach—which sends the signal to your brain to say ‘you’re full, stop eating’—I think that gets triggered faster in weightlessness than it does on Earth,” Smith says.

“We tell crew members all the time, you need to be getting enough to eat. If you think you’re eating enough and we’re telling you you’re not, or the app is telling you that you’re not getting enough calories, you need to push more in,” Smith says. “Even though your brain is telling you you’re full you have to keep going.”

The reasons that Smith and his colleagues want their crews to make weight are many. “We know when you lose weight during flight that you lose more bone than you need to, more muscle than you need to. Your cardiovascular system doesn’t do well, oxidative damage goes up,” Smith says. It’s not a pretty picture. Smith and his team have seen astronauts come back in bad shape after losing 10 percent of their body weight, and they’d prefer that not happen again.

Exercise helps, and encouragement to keep eating when full can help astronauts stay on track. But there are a few other solutions as well—which is where we circle back to fat.

“Crew members that eat more fish lose less bone,” Smith says. “We maintain that omega-3 fatty acids are protective to bone health in astronauts, and frankly in the general population.”

That doesn’t mean you can just include an omega-3 supplement with your cheeseburger and have healthier bones right off the bat. Smith sees the best bone health in astronauts who eat pescetarian; other forms of meat may actually hurt your bones, so sticking to a diet where fish is the only animal flesh is ideal when you’re in space. Looking forward, Smith hopes NASA can incorporate more fish, fruits, and vegetables into the standard astronaut diet. He notes that nutritional support will be even more important when we venture out of orbit to take on more ambitious missions.

“if you look historically at exploration on Earth we learned a lot about nutrition the hard way—sailors getting scurvy is one key example,” Smith says. We may not yet know the exact effects of long term spaceflight on an astronaut’s body, but we do know that fresh veggies (and healthy fats) are crucial to their wellbeing. “As we talk about going to the moon or off to Mars, food is one thing we know we’re going to provide,” he says. “It’s the one countermeasure we know is going to be available.”