One would assume that many of the strongest members of our species are elite athletes. And if particularly strong arms are what you’re after, collegiate rowers—who routinely exert many times their body weight in power to propel a boat forward as fast as humanly possible—are about as good as it gets. But according to a new study, even elite female rowers have nothing on the arms of prehistoric women.

In a study out this week in the journal Science Advances, researchers at the University of Cambridge compared the bones of women living in Central Europe during the first 5,500 years of farming to those of typical college students, as well as members of the school’s women’s crew team. Apparently, prehistoric women would have made pretty decent rowers. They might even have blown other teams out of the water.

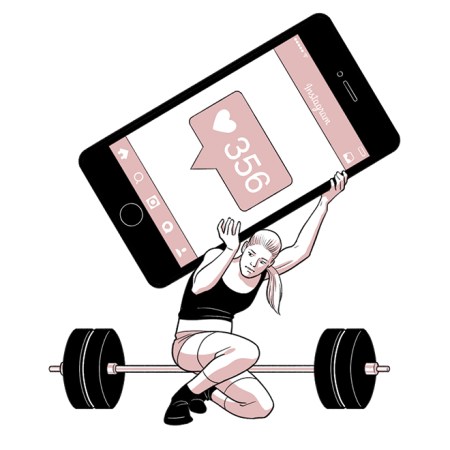

Agriculture was just taking hold over hunting and gathering, and women were doing some hefty workouts. They harvested crops and ground up grain, without any fancy machinery. When the researchers compared humeral rigidity, a measure of bone and muscle strength, prehistoric women had upper arms that were stronger than both average college students as well as members of the competitive rowing team. The researchers think the repetitive motion required in grinding grains led them to possess such powerful arms.

This comparison is the first of its kind. In the past, scientists haven’t done a particularly good job of estimating the strength of women who lived centuries before us. In fact, researchers have actually never compared ancient female bone remains to those of women living today until now. Instead, they’ve compared them to those of men from the same time and region.

But that doesn’t accurately estimate a woman’s strength, says study author Alison Macintosh, an archaeologist at Cambridge. Results from such studies likely underestimate the physical demands required of women during that time.

Bone is a living tissue, just like the muscles that surround it. Efforts like physical impact and increased muscle activity can strain bone and lead to distinct changes in shape, thickness, and density. But the way a biologically male bone changes is much more dramatic than a biological female’s. There isn’t a linear relationship between workload and bone damage. The reason, Macintosh says, is that testosterone and estrogen affect the bone’s inner and outer surfaces to different extents.

“Testosterone promotes the building of bone on the outer surface, where it is mechanically advantageous and has large impacts on bone strength, while estrogen tends to promote packing of bone density and activity on the inner contour, which doesn’t have as large of an effect on bone strength,” says Macintosh.

In other words, attempting to determine the strength and demands on women’s bones by comparing them to men’s is ridiculous. Yet until now, scientists have contented themselves comparing these apples and oranges.

In the new study, Macintosh and her team instead compared the bones to living women: runners, soccer players, rowers, and those with more sedentary lifestyles. Most interesting, though, were the rowers, because their sport—the repetitive movement of the rower’s arms and their legs—is closest to the presumed daily demands of prehistoric women.

It turns out that the average Neolithic women (those living from 7,400-7,000 years ago) had leg strength about on par with collegiate rowers, but arm bones that were 11 to 16 percent stronger than the rowers, and about 30 percent stronger than a typical college student (at Cambridge, at least). Bronze Age women (who lived from 4,300-4,500 years ago) had arm bones about 10 percent stronger than rowers, but their leg bones were around 12 percent weaker.

That makes us working professionals (who mostly just exercise finger muscles while sitting all day) seem pretty wimpy. Even semi-elite rowers might not have been able to hack it in prehistoric years. Women at the time had to grind grain by hand, pounding two large stones together over and over again in what’s called a saddle quern. This was often done for hours at a time. In fact, in the few areas of the world that still use this technique, women grind grain for up to five hours a day.

But Macintosh says that’s not all that contributed to their strength. They also fetched water, milked cows, and converted hides and wools into clothing. In fact, when the researchers compared the tibial (leg) bone strength among modern, living women and prehistoric bone remains, they found a wide range. Some prehistoric women had the legs of elite distance runners, while others’ looked more like those of sedentary college students. This suggests, says Macintosh, that there was a wide variability in what women in those societies did.

In the future, Macintosh plans to continue working on these comparisons to uncover more secrets about the hard working women of the past. “We are currently working to expand what we can interpret about a person’s life form their bones alone, by collecting more data from living men and women, and incorporating information on their muscle and fat as well.”

But this study isn’t just exciting because of its immediate findings. After years of misleading conclusions based on a misunderstanding of female bones, there’s no telling what else we might learn from comparisons like these in the future. As Macintosh points out in the paper, these discoveries will help us fully understand how women adapted to various work loads—and how their labor has shaped cultural history.