To mark our 150th year, we’re revisiting the Popular Science stories (both hits and misses) that helped define scientific progress, understanding, and innovation—with an added hint of modern context. Explore the entire From the Archives series and check out all our anniversary coverage here.

To read the harrowing tales of death and destruction in Popular Science’s May 1962 story, “The Biggest Birds That Ever Flew”, it’s hard to imagine why so many passengers traveled so willingly aboard hydrogen-filled dirigibles. Part tribute, part eulogy, the 1962 story—penned by military historian A. A. Hoehling and Popular Science editor Martin Mann, and published on the 25th anniversary of the Hindenburg disaster—even opens with an epitaph: “The sky has never seen anything to match the giant Zeppelins. Like luxurious airborne hotels—with promenades, staterooms, dining salons, showers—they swiftly flew passengers over oceans. Yet tragedy flew with them until final disaster, 25 years ago this month, sealed their doom.”

In their heyday, the great Zeppelins were the way to travel, making transatlantic crossings in mere days and carrying passengers in luxurious accommodations. There was no shortage of imagination about how airships might be put to use, even as floating laboratories. But the Hindenburg disaster and the destruction of German airship facilities during WWII ended their reign. Or did they?

To a world obsessed with speed, resurrecting airships might seem counterintuitive. But 85 years after the Hindenburg went down in flames, the vessels may have a part to play in a greener air-travel future. A series of companies have plans to enter the market, leveraging non-flammable helium and sporting design advances like mooring-free landing gear and incredible fuel efficiency. Aviation giants like Lockheed Martin have built prototypes but appear to be waiting for relative newcomers like UK-based Hybrid Air Vehicles and Sergey Brin’s LTA Research to kickstart the big-bird market. Besides being greener than airplanes and freighters, airships don’t require runways or harbors, liberating them to come and go from remote or disaster-stricken regions. There’s also the luxury travel aspect: Beginning as soon as 2024, OceanSky Cruises plans to offer roundtrip voyages to the North Pole from Norway’s Svalbard islands and a separate air-expedition above the African continent.

“The biggest birds that ever flew” (A. A. Hoehling* and Martin Mann, May 1962)

The sky has never seen anything to match the giant Zeppelins. Like luxurious airborne hotels—with promenades, staterooms, dining salons, showers—they swiftly flew passengers over oceans. Yet tragedy flew with them until final disaster, 25 years ago this month, sealed their doom.

They were unbelievably long-as much as a sixth of a mile. Their shadows darkened several city blocks. They held gas enough to heat a small town for months.

In the caverns of their compartments they carried, with space to spare, dozens of passengers and colorful loads of bulky cargo: circus animals, sports ears, even airplanes. Voyagers paced their promenade decks, stretched out in smoking lounges, even sang in shower baths.

The Zeppelins looked like whales and handled like submarines. But the sky was home.

They were the biggest birds that ever flew. There had been nothing remotely like them before they came. There has been nothing remotely like them since the last died in flaming public death. That happened just 25 years ago this month. Yet already one of the boldest achievements of aviation science is nearly forgotten.

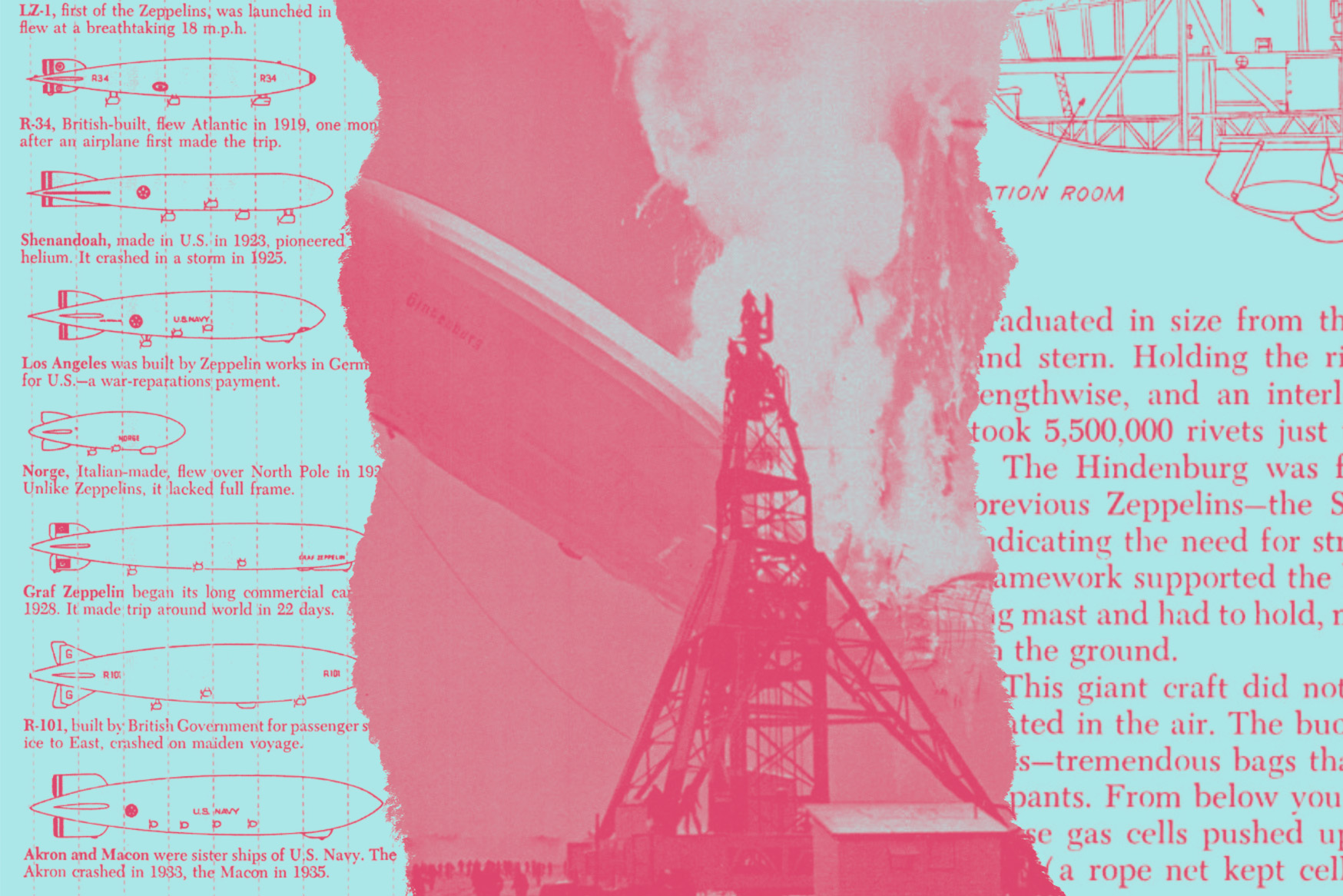

On Thursday, May 6, 1937, the great gray bird droned over the eastern coast of the United States, inbound at the start of her second season of regular transatlantic service. The day was warm and stormy. She was already 10 hours late. And now she had to stooge over the Jersey beaches, waiting the forecasted clearing of the weather. This was the largest and most extravagant aircraft ever flown. Her builders had labeled her LZ-129–the 129th Luftchiff (airship) Zeppelin—and christened her Hindenburg (after the World Var I field marshal who was conned by Hitler into surrendering control of Germany).

In the staterooms, impatient passengers tidied up their valises.

At the Lakehurst, N. J., landing field waited a corps of reporters, photographers, even a special radio-broadcasting crew. Supervising ground operations was the U.S. Navy’s foremost lighter-than-air expert, Cmdr. Charles E. Rosendahl.

Now, in the twilight shortly after 7 p.m., the Hindenburg ponderously nuzzled up to the mooring mast.

In 1937, this was the way to travel—the quickest, most comfortable transatlantic crossing possible. The fastest ocean liners took nearly twice as long. Commercial airplane flights were still two years in the future.

The Hindenburg had departed Frankfurt on Monday, May 3, to the customary fanfare of glowing press notices. Aboard climbed the passengers, surrendering their matches and cigarette lighters as they entered: Mrs. Marie Kleeman bound for a visit with her daughter in Massachusetts, Joseph Spah, an acrobat returning from European engagements, Poetess Margaret Mather flying home to New Jersey, and 33 others. The crew was headed by the veteran Luftschifführer Kapitän Max Pruss.

There was no foreboding of historic tragedy as the command “Up ship!” resounded. This was a gay adventure. If you were a Very Important Passenger, you could count on a tour of the fantastic ship. It was an opportunity not to be missed, for the Hindenburg was a masterpiece of engineering.

The sheer size made your jaw drop. This Zeppelin was enormous: 185 feet across the middle and 804 feet in length. From stern to bow she extended more than three city blocks. If stood on end, she would have reached the 67th floor of the Empire State Building, and towered over the Washington Monument.

The inside of this monstrous football was equally impressive. You walked to the nose along the Kiellaufgang-a narrow aluminum catwalk atop the kecl girder. There was no railing; except for a few guidelines, only a maze of cross-bracing wires and the thin fabric of the hull separated you from the Atlantic Ocean 600 feet below.

From the nose, you looked back on the elaborate blue-painted skeleton—“It seems like a cathedral,” one captain had rhapsodized. The lateral support for the fabric skin was 50 aluminum rings (not truly round, but 36-sided polygons), graduated in size from the fat middle to the pointed bow and stern. Holding the rings were 35 flat girders running lengthwise, and an interlocking cobweb of steel wires. It took 5,500,000 rivets just to fasten the rings to the girders.

The Hindenburg was fatter across her midsection than previous Zeppelins—the Shenandoah had snapped in two, indicating the need for strength amidships. But the heftiest framework supported the bow, for it hooked onto the mooring mast and had to hold, no matter how gusty the conditions on the ground.

This giant craft did not fly like a bird or an airplane. It floated in the air. The buoyancy came from 16 separate gas cells—tremendous bags that were shaped like gigantic pairs of pants. From below you saw only the floppy “pants legs.” These gas cells pushed up against the “ceiling” of the airship (a rope not kept cells from chafing against the hull).

Your tour guide would avoid mentioning it, but those gas cells contained 7,000,000 cubic feet of hydrogen, the lightest gas known-and also the most powerfully explosive. U. S. airships used helium, not quite so buoyant but not at all inflammable. Germany had no helium. Already the black clouds of World War II loomed, and Americans were in no mood to supply rare strategic material to a future enemy.

The Hindenburg’s designers understood the danger. Chimneylike Gasschachte (shafts) vented any seeping hydrogen to the outside of the hull. You caught sight of riggers, wearing buttonless asbestos suits and felcsoled shoes to avoid any chance of static sparks, inspecting those shafts. They also checked the gas cells—they walked right through them along the Mittellaufgang, the hull-bracing axial catwalk that pierced the cells by way of little canvas tunnels.

Walking aft past the officers’ quarters, you came to the Fiihrergondel, the control car. Window-walled, roomy, and impressive, it resembled the bridge of a ship.

Right away, you noticed that it took two men to steer a Zeppelin. The rudderman, facing forward, kept her on course with his giant wheel. The elevatorman faced sideways, watching an inclinometer and altimeter to keep her at the charted altitude. The up-and-down steersman had an unusual and valuable instrument: a crude forerunner of today’s radar altimeter. It was a compressed-air whistle. By timing the beep-beep echoes bounced back from the surface below, he could tell exactly how high he was.

A precise measure of altitude was vital in dirigibles, for they cruised ridiculously low by airplane standards—usually the height above the surface was less than the ship’s length. This was a hazard: A vagary of wind might slam the tail down to disaster (the Akron apparently crashed just that way). However, high altitudes were uneconomical: Too much gas had to be expelled to come down again.

Beyond the Fiihrergondel you came to passenger country. It was spectacular—an amazing replica of first-class oceanliner accommodations, extending all the way across the width of the ship and one-third the depth up from the keel.

There were two decks. The main deck had promenades on either side lined with wide, slanting windows and overlooked by a lounge and the dining salon (hot biscuits, baked fresh in the galley, were a specialty).

Off the foyer on A deck was a narrow corridor leading to the 25 Fahrgastriiume. Each stateroom had two bunks, a stool, folding shelf, fold-up plastic washbasin, mirror, and electric light.

You could even smoke aboard this airship. The bar was sealed off by double doors, which the steward unlocked when you rang the bell. Here the air pressure was maintained slightly above that in the rest of the ship so that no stray hydrogen could possibly leak inside. The smokers lit up with electric lighters (matches were verboten anywhere aboard).

If you wanted to take a shower (imagine that aboard a jet airliner!), you went down to the Badzimmer on B deck. It gave a trickle of water until an automatic shutoff unmistakably told you “time’s up.” Water was too heavy to be carried in lavish supply—they augmented tank storage by collecting rain and dew that ran off the Hindenburg’s four-acre back.

Everywhere, ingenious touches economized on weight. Each extra pound meant 13 more cubic feet of hydrogen. You could lift any of the chairs with a finger of one hand. You needed two hands to raise the piano, which was made of aluminum. The partitions—even stateroom walls—were canvas; it was like living in a many-roomed tent.

Beyond the passenger quarters stretched two-thirds of the giant craft. You walked past three crew foc’sles, one major and 14 lesser freight rooms, two dozen lockers for ship’s gear, 15 water-ballast tanks, 42 tanks storing 64 tons of diesel fuel.

Each of the four engines-1,100-hp. Mercedes-Benz diesels driving 20-foot four-bladed wooden propellers—wvas carried with its operator in a Motorgondel, a little car hanging outside the hull. You climbed into it by a narrow ladder leading down from the lower catwalk. Inside, the roar was deafening —the telephone connection to the control car was useless, and instructions had to be signaled over an engine telegraph like those in steamships.

The Hindenburg could make 84 knots top, and cruise at 77 knots—not too far behind commercial airplanes of the day. She also had something no airplane ever has—a spare engine stowed in a freight compartment.

At the very stem inside the huge under fin was a retractable tail wheel, similar to one under the control car. At Lakehurst the tail wheel rested on a flat car that rolled around a circular track, allowing the airship to turn with the wind when she was tethered to her mooring mast. Huge, complex, and beautiful, the Hindenburg was the supreme creation of the Zeppelin builder’s art. Safe, too. Her designer, Dr. Ludwig Duerr, had boasted that she was as fireproof as man knew how to make any vehicle of transport.

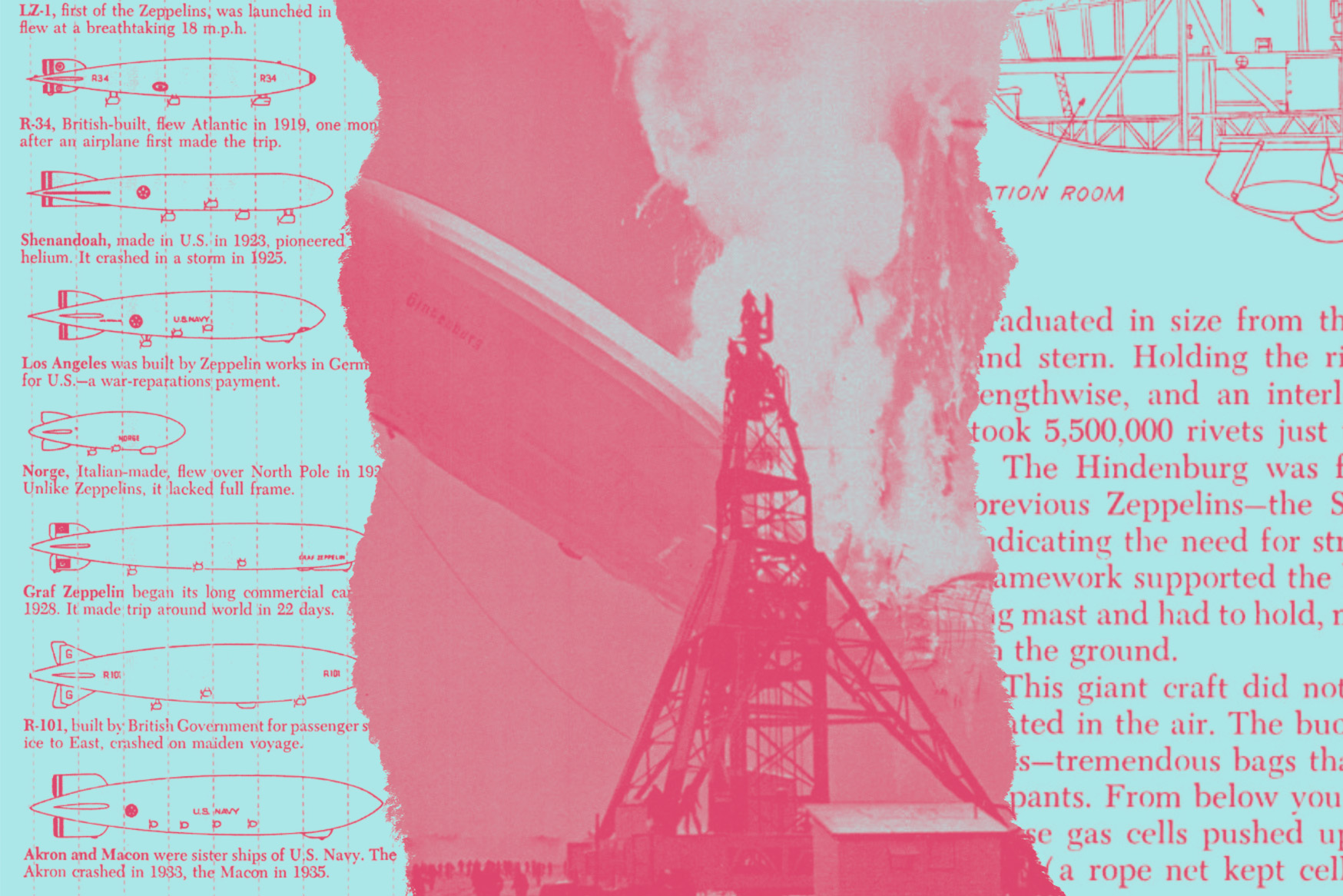

If anyone knew how to build and fly airships, it was the Teutons from Friedrichshafen. Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin had built the first practical dirigible in 1900 (these things were giants from the starcold LZ-1 stretched 420 feet). Ten years later he was hauling passengers in the world’s first commercial air transport. By the time World War I shut down the Deutsche Luftschiffahrt A.G., it had established a most respectable record: 34,228 passengers, 144,000 miles, no deaths, no injuries.

The Germans flew 72 Zeppelins during World War I and sent them on 311 bombing raids. The bomb casualties in England alone came to 1,882 people, not counting a very substantial number hurt by falling shells from the Britons’ own ack-ack. The biggest of these warcraft, the 700-foot L-72, was poised to cross the Atlantic and strike New York, but peace came just in time.

The victorious Allies, impressed by this record, took over the Luftschiffabteilung’s Zeppelins, and rushed to build more of their own. A decade and a half of disaster followed.

In 1921, the ZR-2, built for the U.S. Navy by the Royal Airship Works in England, broke its back and burned, killing 62.

In 1923, the Dixmude (the old L-72, seized and renamed by the French) disappeared on a flight to Africa. The only trace ever found was the body of her captain, Commander du Plessis de Grenedan, pulled out of the Mediterranean by fishermen.

In 1925 the Shenandoah, an American-made copy of the German L-49, broke up in a squall over Ohio, killing 14.

In 1930 the R-101, pride of Britain, exploded against a hillside at Beauvais, France, killing 47 (including the Secretary of State for Air, the Director of Civil Aviation, and most of the Empire’s airship experts).

In 1933 the U.S. Navy’s Akron, which could launch airplanes like an airborne aircraft carrier, plunged into the Atlantic off Barnegat, N. J., killing 73.

In 1935 the Macon, sister ship to the Akron, broke her stem and fell into the Pacific, killing two.

That did it for everybody except the Germans. Back in Friedrichshafen things had gone swimmingly.

In the autumn of 1928 the Graf (Count) Zeppelin—the LZ-127, 774 feet long, weighing 66 tons, able to haul a payload of 20 passengers and 13 tons cargo—inaugurated commercial service. She followed a southern track to America, averaging not quite 60 miles an hour: 6,000 miles from Friedrichshafen to Lakehurst in four days and 16 hours.

The New York Times gave nearly 10 pages to the story.

The following year the Graf flew around the world. In 1980, service to South America began. By 1936, she had transported 13,000 passengers on 575 trouble-free flights.

Yet the crews became unbelievably careless. They smuggled contraband. They even sneaked cigarettes on catwalks, hiding behind bags billowing with touchy hydrogen.

On one journey from South America, crewmen secreted monkeys in the hull. The monkeys escaped and swung, chattering and scolding, from girder to girder until the ship landed. Another time, tropical fruit, tucked high in the framework, dripped sticky juice on all who passed below. Cameras and radios, a special hazard because they might contain spark-causing batteries, were conveniently concealed in the folds of the floppy gas cells.

Nonetheless, the Craf’s phenomenally charmed life held (she and the U.S. Navy’s Los Angeles, also German-built, were eventually dismantled). The Craf was west of the Canary Islands, homeward bound from South America, as the Hindenburg prepared to moor that thunderstormy afternoon 25 years ago.

At Lakehurst, Lt. Raymond F. Tyler and Chief “Bull” Tobin—both lighter than-air pros—directed the ground crew. They had rolled out the 75-foot tripod mast and deployed the line handlers.

Theirs was a delicate task. It was up to Kapi Kapitan tin Pruss to “weigh off” his Hindenburg: get it nearly level and aerostatically balanced by valving off or adding gas into the various sections, depending on whether the ship needed to be heavier or lighter. But even after a perfect weighoff, it took more than 200 strong men to haul the balky colossus down from the sky. Troops from Camp Dix had been drafted to help 138 civilian and 92 Navy linesmen. The least gust of wind could and often did—send the airship bounding like a kangaroo hundreds of feet skyward. On other occasions rope handlers had been lifted before they could let go, then dropped to their doom.

The Hindenburg swept in over the south fence at a brisk 73 knots, 590 feet high.

“What a sight it is!” exulted Herb Morrison, the Chicago radio commentator who was making an eyewitness recording on the field. “The sun is striking the windows of the observation deck and sparkling like glittering jewels on black velvet….”

Kapitan Pruss crossed the field and tuned to come in, valving gas from forward cells, dumping water ballast from the stem, shifting crewmen for an exact balance.

At 7:21 p.m., the first handling rope hit the ground.

In the passenger compartment, photographer Otto Clemens leaned out a window and worked his Leica to record the action below. He did not know it until his film was developed days later, but his negative showed flame reflected in rain puddles on the ground.

A bystander, Cage Mace, recalled later, “A shower of sparks shot up from the top of the bag and to the rear, followed instantly by a column of yellowish flame…”

Above, passengers tumbled, one atop the other, a mass of shrieking, crying people.

Joseph Spah, the acrobat, knocked out a window, climbed through, and dangled outside by one hand. When the ship started falling, he dropped—hard enough to bounce.

Miss Mather was pulled out of the crumpling, flaming cabin by ground crewmen.

Frau Kleeman just walked down the debarkation stairs.

In half a minute, 35 people were killed or fatally hurt.

Even today, 25 years later, your back chills when you listen to the recording of newscaster Morrison’s sobs: “…Get this, Charlie, get this. Charlie… It is burning. Oh, the humanity and all the passengers!”

More than humanity perished that warm May evening. It was the end of an era. The great airships had become a part of history.

Official investigations arrived at the “least improbable” conclusion: Static electricity had ignited leaking hydrogen. This verdict was not very convincing then, and is less so now. New evidence points to sabotage by a crew member allied with the Communist anti-Nazi underground (it’s a complex story detailed in the book Who Destroyed the Hindenburg? by A. A. Hoehling, Little, Brown & Co., Boston).

But one more Zeppelin flew: the LZ-130. She cruised the English Channel, ferreting out British radars before World War II, but was ignominiously scrapped for her aluminum.

If you visit Friedrichshafen now, you can sec the ruins of the Luftschifibau, leveled by bomb attacks. Weeds wave above rubble—jagged headstones of the Zeppelin’s own burying ground.

Until his death in 1960, Max Pruss had campaigned for a new airship company. He came close to winning approval for a 150-passenger Zeppelin even bigger than the Hindenburg. In the United States. Prof. Francis Morse of Boston University has blueprinted an atomic-engined dirigible-without much encouragement from anyone who might build it.

The plain facts of transportation explain why. A jet airliner can fly the Atlantic in six hours instead of 60. It can carry three times as many passengers each trip as the Hindenburg did. It costs only a fraction as much to build.

The biggest birds that ever flew are gone—extinct as dinosaurs and pterodactyls, and no more likely to return.

*Author of Who Destroyed the Hindenburg? and Martin Mann

Some text has been edited to match contemporary standards and style.