The city council of Presidio, Texas, voted on June 7, 2021 to approve locating a new camera system for Customs and Border Patrol on city property. The Sentry camera is a re-deployable 30-foot-tall tower bristling with sensors and powered by solar panels. It’s made by Anduril, a security technology startup. As the city council agenda notes, Presidio approved locating one such Sentry “on city property near the City of Presidio Waste Water Treatment Plant.”

Presidio, population 4,000, sits on the US side of the confluence of the Rio Grande and Rio Conchos rivers, across from Ojinaga in Mexico, in the broader Big Bend region of the state. Its wastewater treatment plant feeds into the nearby B.J. Bishop Wetlands, a human-created wetland fed by treated wastewater that functions as a bird sanctuary. This wetland sits just less than a mile from the Rio Grande, and from the border.

It is this proximity to the border that drew the interest of Customs and Border Patrol, which already operates a checkpoint on the legal crossing between Presidio and Ojinaga. Anduril boasts that any installed tower occupies just 256 square feet, or a square 16 feet on each side. With a low-impact deployment (the company says it involves “zero digging and minimal disturbance to land and migratory animals”), the towers can be installed to watch an area without disturbing the natural flow around it.

Instead, the Sentry towers are designed to watch the movements of people and vehicles.

Beyond work on the border, the Sentry system has found a home helping with base security for the Marine Corps, aiding in surveillance in areas where cell signals can be spotty. It’s a sensor suite, complete with an easy deployability, that could transfer from static installations in the United States to a ready-made base security tool abroad.

Customs and Border Patrol, housed within the Department of Homeland Security, requested funding for the towers last year. CBP’s budget request, Defense Daily reported, described the technology as “an autonomous solution capable of detecting, identifying, and tracking illicit cross border activity.” That autonomy includes categorizing movement nearby as human, animal, or vehicle, with a radius of 1.5 miles for tracking humans and over 2.5 miles for tracking vehicles.

[Related: The Air Force’s new guard dogs are robots]

That gives each Sentry an area of roughly 7 square miles in which it can watch people, and over 19 square miles in which it can watch for vehicles. The Sentry watches with both electro-optical and infrared cameras, as well as radar and other sensors. This information is shared over LTE and mesh networks, and then refined by the company’s Lattice AI system on NVIDIA processors.

A tower like this puts cameras on an area so it can be remotely monitored, instead of patrolled on foot or by vehicle. While freeing people from monitoring in the field, remote cameras can still often require human operators to view them remotely to make them useful. Anduril is explicit in its pitch to offer cameras without increasing that labor load, highlighting its Lattice AI system as a way to “[scale] awareness without scaling headcount.”

“Each Sentry Tower autonomously handles the task of detecting people, vehicles or animals,” the company’s material reads. “Lattice AI is more accurate at recognizing threats than human operators and requires fewer staff to secure a location.”

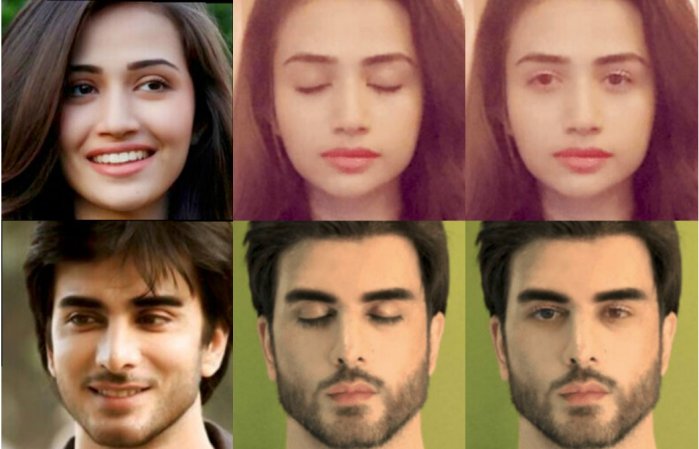

Artificial-intelligence-powered recognition systems can fail in a variety of ways, a challenge that only becomes more loaded the closer those sensors and algorithms are towards directing action by armed security forces. Setting aside harm from error in recognition software, border surveillance has shown to shift how and where people decide to cross into the United States. Sam Chambers, a geographer at the University of Arizona, studied “whether migrants took new routes to avoid increased surveillance, and whether those new routes put them at higher risk of heat exposure and hyperthermia,” High Country News reports. This analysis included an estimate of where in terrain a person could move out of sight of a surveillance tower, incorporating the energy cost of hiding from detection into a broader calculus of how people expend energy when trying to cross a border.

Cameras like Sentry, powered by AI or not, exist to make people on (or near) the border visible to the government. Specifically, they make people visible so that border patrol can detain, search, and then process undocumented people along the border, an interaction that primarily leads to imprisonment followed by deportation.

[Related: DARPA wants cave robots that can scout ahead for threats or missing people]

And a system like this with cameras is naturally going to prompt questions about privacy. The Big Bend Sentinel reports that, while privacy concerns were not discussed at length in the meeting, the Border Patrol agent in charge of the Presidio Station Silverio Escontrias did say that “the towers can be programmed to exclude, or block out, certain geographic regions of the city.”

Border surveillance can attract special attention from both Congress and the public. In 2017, the Government Accountability Office published a report on Border Patrol surveillance technology that emphasized a need to improve both data quality and effectiveness. The Electronic Frontier Foundation, a digital rights group, maintains a map of surveillance technology deploying along the US-Mexico border, highlighting risks of biometric data capture to anyone in the region.

The sentry watches. And, filtered through AI, it provides information for humans to act upon.