On January 27, a discarded Russian rocket stage and a defunct Russian satellite passed within yards of each other in orbit over Earth, narrowly avoiding a collision that would have generated hundreds or thousands of bits of dangerous space debris.

Had either object been a working satellite, its owners and operators would have received an advanced warning, in the form of an email, from The 18th Space Space Control Squadron of the US Space Force. The US military has been the de facto global space traffic controller for more than a decade—but that role may be coming to an end, with plans for the US Department of Commerce to take over that job.

The day before the near-miss, the Commerce Department issued a Request for Information asking for public and industry comment on a list of proposed services for the department’s Traffic Management System for Space, or TraCSS program—a civilian-run system planned to track objects in space and avoid collisions. Situated in the department’s Office of Space Commerce, TraCSS will predict when objects reenter the atmosphere, forecast space weather, and warn of potential collisions, among other services. The Commerce Department wants feedback on how it can best implement those services to “enable a competitive and burgeoning US commercial space sector,” according to the request.

[Related: This meteor-tracking system could prevent a falling-rocket debris disaster]

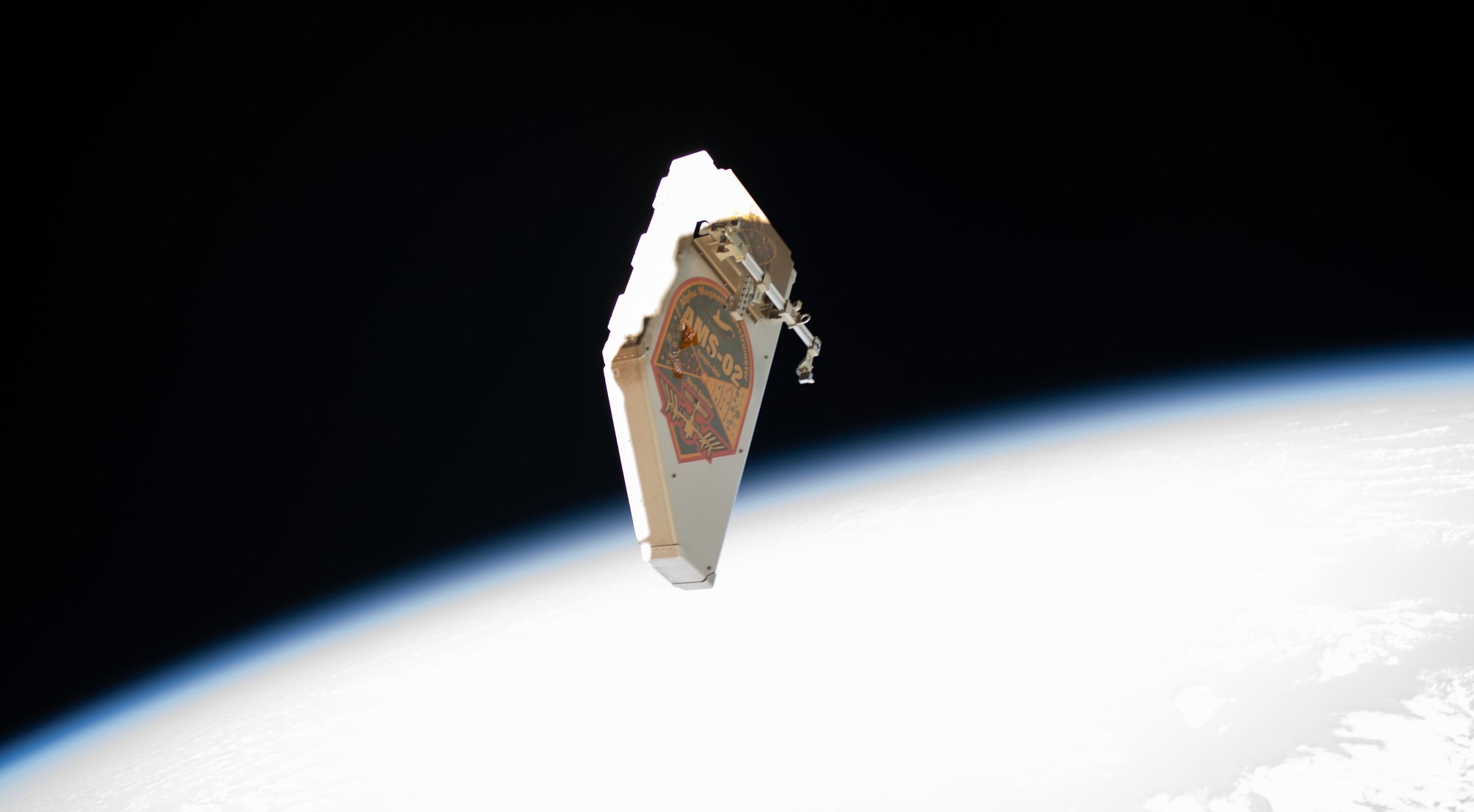

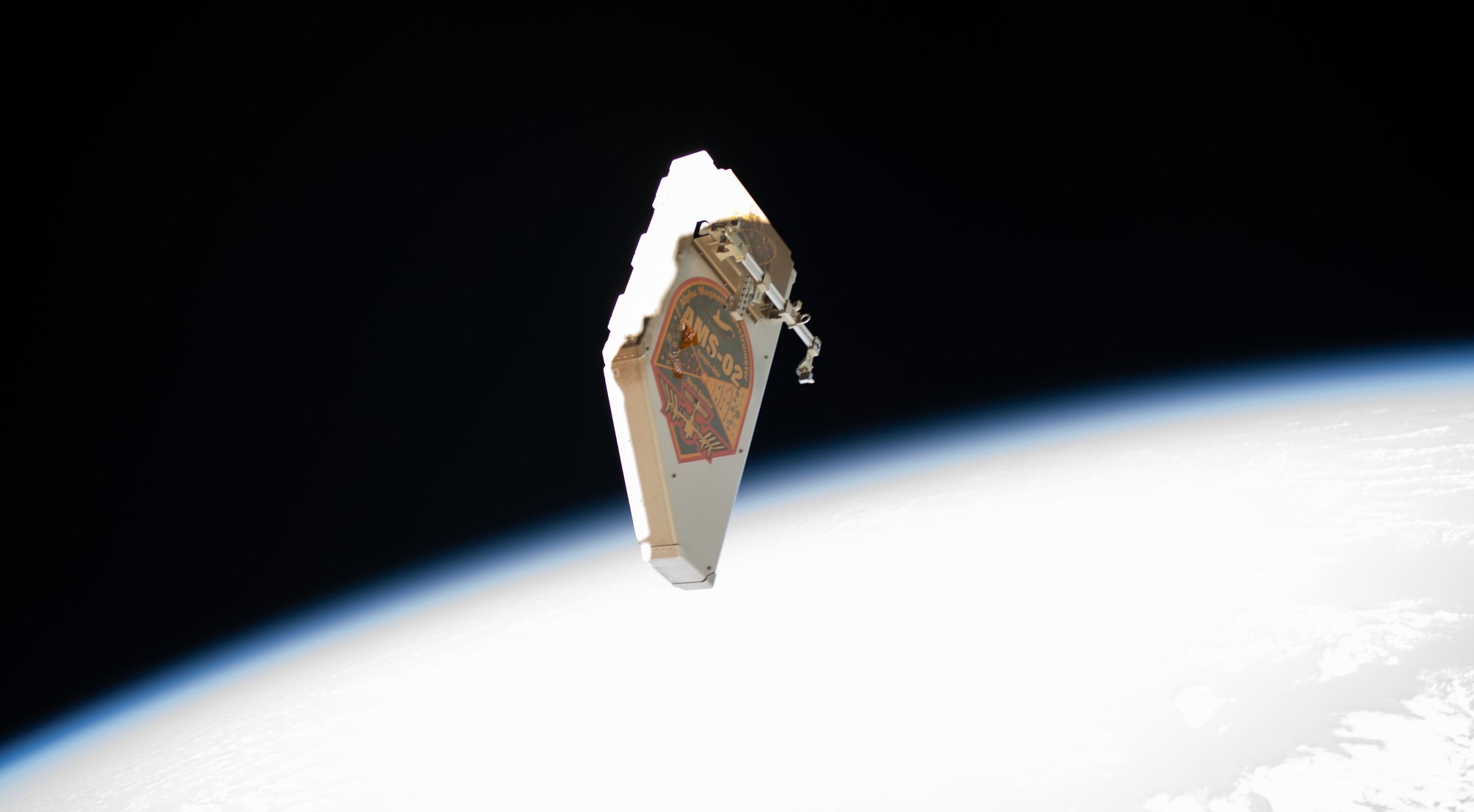

Whether run by the military or by a civilian agency, some form of traffic coordination and space junk monitoring is essential to the rapidly growing commercial space industry. There are now more than 4,800 functioning satellites in orbit, and SpaceX alone plans to launch up to 60 of its Starlink satellites roughly each week this year—they launched 53 satellites into low Earth orbit on February 2.

Add to the mix roughly 20,000 pieces of space debris of varying size traveling at tremendous speeds, and the hazards of uncoordinated space flight become clear, according to Robin Dickey, a space policy and strategy analyst with The Aerospace Corporation, a federally funded research organization that has advised the Commerce Department on space traffic issues.

“In low Earth orbit, objects are traveling as fast as 17,000 miles per hour,” she says. “So the actions of any one actor, any one satellite in space can affect everyone.”

The sheer volume of objects that need tracking, and potential collision alerts, led to the Trump Administration’s Space Policy Directive 3 in 2018, which directed the Commerce Department to begin preparing to take over space traffic management from the military. The directive cited the need for the US military to focus on protecting its space assets rather than managing civilian space traffic.

In December 2020, Congress passed legislation directing the Office of Space Commerce to begin working on the project; the incoming Biden Administration picked up the nascent program. Two years later, the department announced pilot program contracts for commercial contractors to assess their ability to aid in space traffic management. The current deadline for the office to take over from the military is fiscal year 2024.

That may be a tough deadline to meet, according to Moriba Jah, an aerospace engineering and engineering mechanics associate professor at the University of Texas at Austin and co-founder and chief scientist of orbital debris tracking company Privateer Space.

“I like the fact that things are moving in this direction, but sometimes it’s good to move quickly without haste,” Jah says. “I feel that there is haste going on in putting this stuff together.”

[Related on PopSci+: How harpoons, magnets, and ion blasts could help us clean up space junk]

The TraCSS program will be able to access military space tracking data and take advantage of information from commercial space companies, which have their own sensors and instruments. But the real challenge for TraCSS, Jah says, will be combining all of that information in a way that is understandable and consistent for space operators. These managers, found in civilian and government space organizations, must make decisions on whether to move a satellite to avoid a potential collision.

With these ambitions, the engineers and developers behind TraCSS have a lot of work to do. “That’s not going to happen in a matter of months or a couple of years,” Jah says. “That’s really hard.”