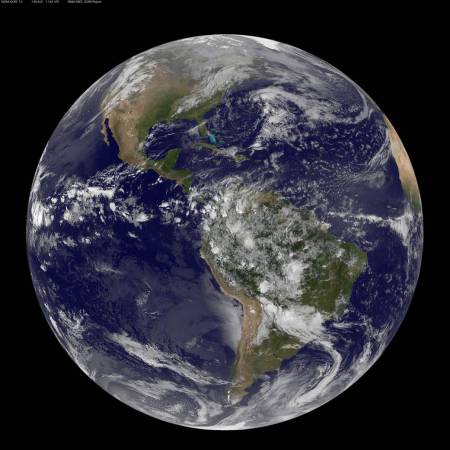

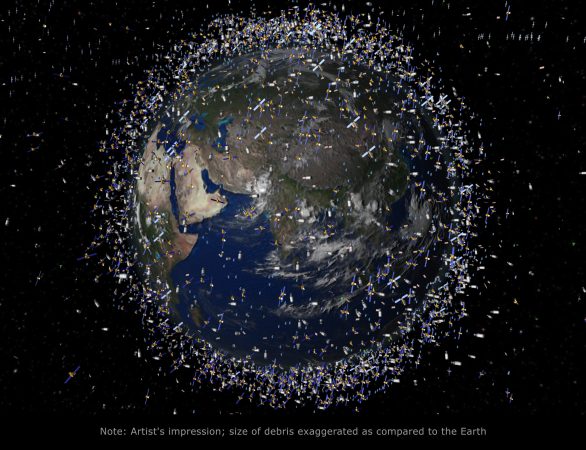

IN NOVEMBER OF 2021, the crew of the International Space Station briefly went on lockdown after they were pummeled by shards of metal from a retired satellite blown up during an unannounced Russian military exercise. According to NASA, the Department of Defense currently tracks more than 27,000 pieces of similar orbital debris, aka space junk. But many other bits of trash are too small to keep tabs on. Hurtling at speeds of 17,500 miles per hour—and without the friction of an atmosphere to burn them up—even minuscule flecks of rocket paint can spell doom for an astronaut or flying craft. And while accidents have been rare, the rise of commercial space traffic (54 launches in 2021 alone, compared to the previous record of 33 in 2018) has exponentially increased the risk of these potential collisions.

[Related: This meteor-tracking system could prevent a falling-rocket debris disaster]

“The amount of material is stacking up,” says Mariel Borowitz, an associate professor at Georgia Tech who specializes in international space policy and security. But decluttering the final frontier is easier said than done. Besides cost, Borowitz says, the question of who can do the cleaning remains murky. If NASA puts a satellite into orbit, she explains, “it belongs to the United States even if it breaks into pieces.” The same holds true for any company or government. If you wanted to tidy up someone else’s junk, she says, you still wouldn’t have the right to do it.

Fortunately, many countries and companies are handling that quagmire by testing ways to deal with the trash, whether it’s a Japanese satellite that sets magnetic traps or a four-armed plasma bot named Fred. Here are six of humanity’s most promising projects for monitoring and clearing out the heavens.

RemoveDebris

ORIGIN: UK

COST: $18 MILLION

DEPLOYED: 2018

M.O.: HARPOON HUNTER

Weighing in at about 220 pounds, this target-savvy satellite combines a harpoon that shoots out at 65 feet per second with a net that’s 16 feet wide to trap space junk and pull it back to Earth’s atmosphere. Two cameras record the process so that officials on the ground can assess the waste’s trajectory as it falls.

But don’t let the name throw you off: RemoveDebris isn’t removing debris quite yet. Launched in 2018, the system is currently being tested outside the International Space Station. It practices catching experimental targets (like small satellites called CubeSats) using a detection system with lidar and 3D vision tech similar to that of self-driving cars. But even though it’s not quite ready, it already has multiple collaborators (including SpaceX and Airbus) and is one of our brightest hopes for pulling refuse out of thin air.

SPMN

ORIGIN: SPAIN

COST: $22,350/YEAR

DEPLOYED: 1996

M.O.: THE SPY NETWORK

Fireball networks, which consist of strategically placed cameras rigged to follow meteorites through the skies, exist all over the world, from the Czech Republic to Australia. The Spanish Meteor and Fireball Network (SPMN) was originally founded in the 1990s to study cosmic rocks with the rest of them. But in 2021, it detected something new: pieces of an incoming SpaceX rocket burning up over the coast. That further proved that the tool could be used to track the paths of organic and artificial matter as they approach land.

Currently made up of 34 ground stations and 150 high-resolution cameras positioned around the Iberian countryside, SPMN can alert local authorities to reentries or meteorite falls. More widely, the project aims to help people understand the rare yet present terrestrial dangers that come from increased space activity over the years.

Solar CubeSat

ORIGIN: US

COST: $875,000

DEPLOYED: 2025 (EST.)

M.O.: SOLAR SURFER

When it comes to long-term solutions, it’s sometimes best to think small. CubeSats, 4-inch-wide nanosatellites, have been used to conduct space research since 2003. Now student engineers from Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Florida have modeled one specifically to take out the trash.

The Solar CubeSat prototype uses a compact robotic arm to reach out and capture free-floating objects up to about 4 inches away. Unlike many other would-be cleaners, this wee satellite won’t run out of fuel and become more junk: It packs a deployable sail that catches the power of the sun’s rays, which means it can keep breezing through low Earth orbit for as long as its hardware holds up.

According to the Embry-Riddle team, the prototype is designed to use off-the-shelf technologies and could yield a fully functional model in four to five years.

ELSA-d

ORIGIN: JAPAN

COST: UP TO $191 MILLION

DEPLOYED: 2021

M.O.: MEGAMAGNETS

Unlike the other high-flying machines on this list, End-of-Life Services by Astroscale (ELSA-d) won’t be cleaning up garbage that’s already in orbit. Instead, its makers are banking on future satellite engineers to incorporate magnetic docking plates into their designs—and pay for ELSAd’s assistance when the time comes.

This angel of death takes the form of a 385-pound winged “Chaser,” which relies on optical sensing instruments and a set of small magnets to seek, catch, and relocate its targets. In a 2021 demo more than 300 miles up in the air, ELSA-d successfully caught and released a mini satellite with the custom hardware. The next round of tests will have it nab a compatible object while tumbling, scan the environment for litter on the lam, and pull hunks of metal down into Earth’s atmosphere to slowly decay.

Orbot Fred

ORIGIN: US

COST: NOT PUBLIC

DEPLOYED: 2025 (EST.)

M.O.: CLAW MACHINE

Tech startup Rogue Space Systems is tinkering with a 56-foot-wide plasma-powered vehicle whimsically dubbed Orbot Fred. With two winglike solar panels, it’s built for precision: Four robotic arms will grasp and move a maximum of 700 pounds of garbage away from other satellites’ orbits, then send the haul to burn in Earth’s upper altitudes.

The company hopes to leverage private and public money to get its fleet of Orbots online in the next three years. One of its sources could be SpaceWERX, the innovation arm of the US Space Force, which is looking to outsource some answers to floating junk, in-flight servicing and assembly, and more. In 2021, the department launched a grant program called Orbital Prime that will eventually award contracts of $1.5 million to selected competitors, like Fred’s creators.

Sweeper

ORIGIN: RUSSIA

COST: $2 BILLION

DEPLOYED: 2023 (EST.)

M.O.: STUN GUN

Using ion propulsion thrusters to destabilize dead satellites and push them out of other projectiles’ paths, the Sweeper, like many other orbiting-trash-removal concepts, aims to force debris down into our atmosphere for a fiery finale.

Sweeper is actually one of the oldest proposed missions meant to help keep space collision-free, with the original plans dating back to 2010. Its creator, the Russian rocket company Energia, hasn’t shared any updates on the project, so there are still question marks on all the details. Energia plans to assemble and test the vehicle by 2023. The pod, which might run on nuclear power, will have the capacity to collect and destroy at least 600 defunct transmitters over a 15-year life span. It’s unclear whether it would eventually turn into orbiting junk itself—or whether another Sweeper would need to bring it back to Earth.

This story originally ran in the Spring 2022 Messy issue of PopSci. Read more PopSci+ stories.