You know the feeling: You’re going about your business, living your life, and all of a sudden the Olympics are wherever you look. Every brand has an Olympian in their ads; every commercial on TV is about strength and perseverance. The games take over newspapers, Instagram, and casual conversation at the office.

If you’re one of the unfortunate few who don’t give a hoot about the Olympics, the biennial onslaught may feel overwhelming. After all, most sports fans don’t care about table tennis or pole vaulting when the games aren’t in session, so why should they get so obsessed all of a sudden?

Turns out the appeal of the Olympics is less about the individual sports and more about how the event as a whole caters to different parts of the human psyche. The competition has three key ingredients that spark fervent fandom: curated marketing, compelling personal stories, and an outlet for national pride. Understanding these factors can help you appreciate the enduring power of the games’ tradition—and maybe help you tolerate a few weeks of Olympic fever.

A TV bonanza

The first and most important thing to understand about the modern Olympics is that they are, more than anything else, a media product. Yes, host cities like Tokyo spend millions of dollars building bespoke stadiums and tracks, and yes, thousands of people travel from all corners of the world to attend. But the vast majority of people experience them via TV or the internet.

It took a while, but the games themselves have adapted to that fact over the past few decades, says John Davis, a former professor of business at University of Oregon, who’s written a book about the commercial appeal of the Olympics.

“When it really started to shift was in the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, which was the first truly profitable Olympics,” says Davis. The California games helped to transform the contest into a commercial and media phenomenon. Or as Davis puts it, they “ignited a virtuous cycle—athletes attract fans, fans attract media, and media attracts sponsors.” The stars of the show were the members of the US men’s basketball team, led by Michael Jordan, who himself had ushered in a new era of sports celebrity in the NBA.

Almost four decades later, the Olympics still live or die by their TV success, Davis explains: Six of the 10 most-watched broadcasts in world history are recent Olympics. One of these was the 2016 summer games in Rio de Janeiro, which were dogged by reports of corruption and delay in the lead-up to the opening ceremony. Despite the controversy, though, the games themselves drew 30 million viewers in the US, nearly an Olympic record. The easiest explanation for the outing’s success might have been that Rio’s time zone is only an hour ahead of New York’s, which made it easy to draw big audiences for prime-time events. This year’s event in Tokyo is also expected to draw record-setting viewers despite concerns over the coronavirus pandemic, in part because the main events will be scheduled so as to cater to a US viewership. That means athletes in Japan may compete at odd local times so their exploits can be broadcast live during American primetime or in concert with NBC’s Good Morning America.

Making it personal

Still, the Olympics draw far more viewers than one would expect given the relative popularity of the sports involved. Swimming and ice skating don’t normally get primetime treatment, so what compels people to watch them once every four years?

[Related: Surfers are riding a wave of new technologies to their Olympic debut]

The attraction, says Lisa Delpy Neirotti, a professor of sports management at George Washington University, isn’t the sports themselves. It’s about the narratives we build up around them.

“It does have special meaning because there’s so many amateur athletes [watching the games],” she says. “Anybody who competed in swimming at one point may have thought there would be the next Michael Phelps; almost every little kid tumbled at one point, maybe they could be Simone Biles.”

This is why the individual athletes are so important. Our brains gravitate toward relatable stories, and even those of us who never wanted to be Olympians are familiar with the feeling of working hard toward a difficult goal. That emotional resonance makes it easy for us to get invested in the success or failure of individual athletes like Allyson Felix, especially when the announcers constantly remind us how much the competitors sacrificed to train and earn a spot on the world stage. The growth of sponsorship deals and the advent of the internet have also helped to turn competitors like Biles and Phelps into enduring celebrities, so that their narrative arcs extend beyond any one Olympics season.

This focus on individual performance tends to make Olympic viewers “more forgiving” of athletes than traditional team-sports enthusiasts, says Davis. If you’re a Philadelphia diehard and the Eagles get knocked out of the NFL playoffs, you might be liable to stick your fist through drywall. But if a 100-meter runner you love fizzles out with a bronze, it’s easy for your enthusiasm to shift toward the underdog who came away with the gold.

For Sparta

There’s another, more primal reason we tune into the Olympics, and that’s national pride.

The idea for the modern Olympics emerged from the brain of one Baron de Coubertin, a 19th-century French aristocrat who thought sports were the perfect way to bring the whole world together under the banner of peace and harmony. That might have seemed possible back then, but two World Wars and a Cold War later, it’s not so practical.

Today, says Jeffrey Montez de Oca, a professor of sociology at the University of Colorado-Colorado Springs, the Olympics are a bloodless outlet for nationalism and patriotic sentiment.

[Related: How Abebe Bikila won the Olympics marathon without shoes]

“In the United States, we’ve always loved competition,” he says, “and the Olympics has always been a political space. It’s always been about competitions between nations.” When the Cold War was in full swing, says Montez de Oca, the most important challenge for the US was to beat the Soviet Union, as it did in the famous 1980 medal-round hockey game. Now, though, it’s more about dominating the overall medal count to show that we produce more great athletes than anyone. Either way, the games appeal to our innate tendency toward in-group belonging, a habit that has evolutionary roots in our ancestral pasts. Research has shown that early humans were more likely to survive when they associated and identified with well-defined cliques rather than ranging from cadre to cadre. As a result, some evolutionary theorists think that today’s patriotic feelings could stem from that ancient loyalty.

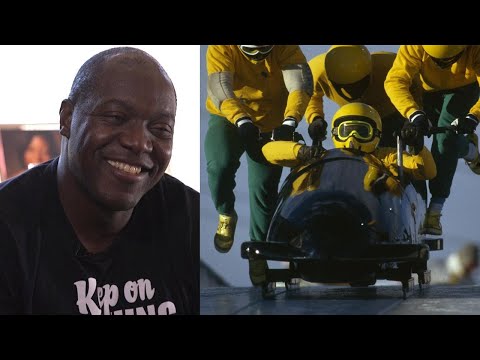

Other countries, meanwhile, have narrower and more specific ambitions. Montez de Oca’s wife is Japanese, and he says that Olympic fans in Japan root for the country to earn more medals than other small countries rather than dominate the overall count. In other countries like India or Norway, viewers may be invested in a less-watched event like archery or the biathlon. (Perhaps the most famous example of this phenomenon was the underdog Jamaican men’s bobsled team, immortalized in the 1993 film Cool Runnings.)

The upshot, then, is that the Olympics aren’t much about the sports at all, but about the meaning we give to them. That might not make the wall-to-wall coverage any less annoying, but it does mean there’s a low barrier to entry for aloof viewers. If you find yourself with a few minutes to spare this summer, maybe tune into some speed climbing. You might find you have a soft spot for one of the self-made dreamers vying for the gold.