The world’s population will top nine billion by 2060. Because of climate-change-induced environmental degradation, scientists project that tens of millions of people will move into today’s small and medium-size cities. To prepare for the influx, says Dennis Frenchman, an architect and professor of urban planning at MIT, city designers must make decisions today to mitigate the migration of tomorrow. And those decisions should focus on making systems more efficient.

Transportation networks need to be rethought to limit congestion. Politicians should offer incentives to manufacturing firms to relocate to city centers to decrease the number of commuters. Power generation and food production should become local, too; reducing transmission and transportation costs would keep prices lower. Further, Frenchman says, single-purpose-use spaces like shopping centers and housing developments should be swapped for mixed-use neighborhoods that contain homes, medical offices, stores, schools and offices. With essential services packed into one relatively small area, even the densest city would feel more like a small town.

COMMUNITY-SHARED ELECTRIC CARS

Lots of people, each with a private car, means lots of traffic, pollution and wasted space in the form of parking lots. The designers of the MIT Media Lab prototype CityCar say communal microcars will alleviate crowded roads. The two-seat, all-electric CityCar is best used for point-to-point trips within a few-mile radius. When not in use, the car folds up and stacks together with other CityCars.

NEIGHBORHOOD NUKES

Power lines can lose up to 425 kilowatts per mile of cable. To reduce loss and keep energy prices lower, cities must integrate power generation into neighborhoods. One possible power source is a microsize nuclear power plant, such as GE Hitachi’s PRISM. The PRISM’s reactors would use recycled nuclear fuel to generate 300 megawatts—enough to supply 240,000 homes.

HYPEREFFICIENT HOUSING

As more people crowd into cities, average apartment size will decrease, probably to about 300 square feet, Frenchman says. To make such a small area feel less cramped, every space in the home must be multifunctional. For example, furniture could fold out of walls, and windows made from transparent OLEDs, like ones that Samsung first demonstrated in 2010, would serve as a TV or could be made opaque on command to reduce cooling costs.

REALLY LOCAL EATS

To keep food-transportation costs down, engineers should construct vertical farms, such as the ones proposed by Columbia University public-health professor emeritus Dickson Despommier, that could provide fresh produce and fish to local neighborhoods. Apartment residents will grow personal gardens on the facade of their buildings with pre-seeded panels plugged into built-in wall slots, says Kent Larson, an architect at the MIT Media Lab.

ALL-IN-ONE RECYCLING

Recycling will limit material waste, but the process is energy-intensive. In the LO2P Recycling Center, envisioned by designers Gael Brule and Julien Combes, a turbine harnesses wind power to run a recycling plant in the building, while carbon dioxide from the plant reacts with calcium to become lime in the LO2P’s mineralization baths. Calera Corporation in California developed the process and today uses the lime to make cement.

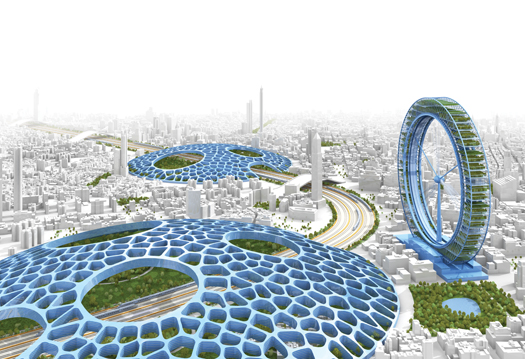

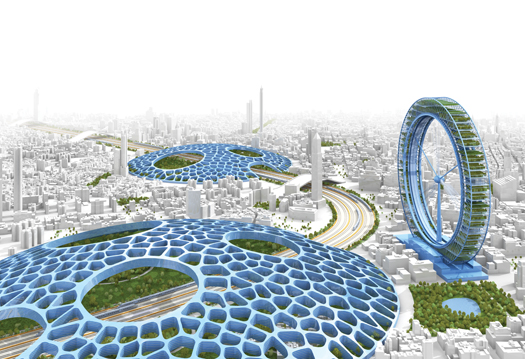

MULTIFUNCTIONAL BUILDINGS

The mixed-use concept is the basis for architect Paul-Eric Schirr-Bonnans’s Flat Tower. In addition to having offices, recreation areas and a rail transit hub, the Flat Tower could house 40,000 people. Schirr-Bonnans says that the conventional skyscraper model—a tower surrounded by green space—leads to the isolation of communities from one another. A greenbelt area under the building would encourage communities to interact.