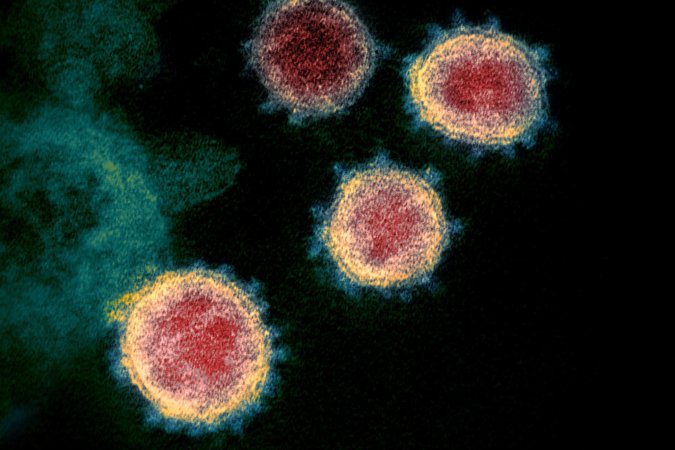

Air pollution is messing with the love lives of fruit flies, warns a new study published on March 14 in the journal Nature Communications. Male common fruit flies had trouble in recognizing their female counterparts after breathing in toxic gas, causing them to make a move on another male.

Though there’s been some research hinting at bisexuality among fruit flies, the current results suggest it has to do more with ozone pollution. Even brief exposure to O3 was enough to alter the chemical makeup of pheromones, a unique trails insects use to detect and attract mates. Increasing levels of air pollutants from cars, power plants, and industrial boilers around the world could stop common fruit flies from reproducing, causing a dramatic decline in the insect species.

[Related: Almost everyone in the world breathes unhealthy air]

The chemical ecologists placed 50 male flies into a tube and exposed them to 100 parts per billion (ppb) of ozone—global ozone levels range from 12 ppb to 67 ppb—for two hours. After two hours, fruit flies showed reduced amounts of a pheromone called cis-Vaccenyl Acetate (cVA) in compounds involved in reproductive behavior.

A closer look revealed that ozone seems to have changed the chemical structure of pheromones. Most insect pheromones have carbon double bonds, explains Markus Knaden, a group leader for insect behavior at the Max Planck Institute of Chemical Ecology in Germany and study author. Whenever a compound has carbon double bonds, it becomes highly sensitive to oxidization by ozone or nitric oxide and starts to separate. The explanation is in line with their findings of high amounts of the liquid heptanal in the flies, a product that emerges after cVA breaks down.

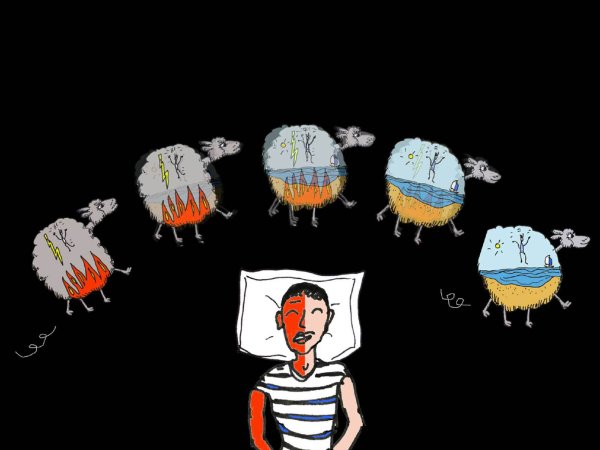

Did the altered pheromones affect a male’s chances at finding a partner? It appears so. A separate experiment exposed male flies to 30 minutes of either ozone ranging from 50 to 200 ppb or regular air with a much lower amount ozone before being placed them with female fruit flies. While males from both groups wasted no time in trying to court females, ozone-exposed fruit flies had more trouble getting a mate.

“The male advertises himself with pheromones. The more he produces, the more attractive he becomes to the female,” says Knaden. Losing the chemical aphrodisiac made ozone-exposed males a less desirable option to females, who took nearly twice as much time choosing from the corrupted bachelors than the clean ones.

Not only is ozone pollution hampering the males’ ability to get female attention, it’s also affecting how they identify other individuals. Knaden says his team expected the altered pheromones to affect the ability for male fruit flies to distinguish between a male and a female, but what they didn’t expect were males to jump on each other. “In the beginning, it was a very funny observation to see really long chains where one male was courting the next and then the next down the line,” he describes. With the altered pheromones, “the male basically jumps on everything that is small and moves a little bit like a fly, regardless of what it is.”

“Very little is known about how air pollution interferes with insect sex pheromone signaling, so it is great to see this work underway,” says James Ryalls, a research fellow in the Center for Agri-environmental Research at the University of Reading in England, who was not affiliated with the research. “The study demonstrates how disruptive air pollution can be to insect communication, with potential ecological ramifications such as reduced biodiversity.”

[Related: Flies evolved before dinosaurs—and survived an apocalyptic world]

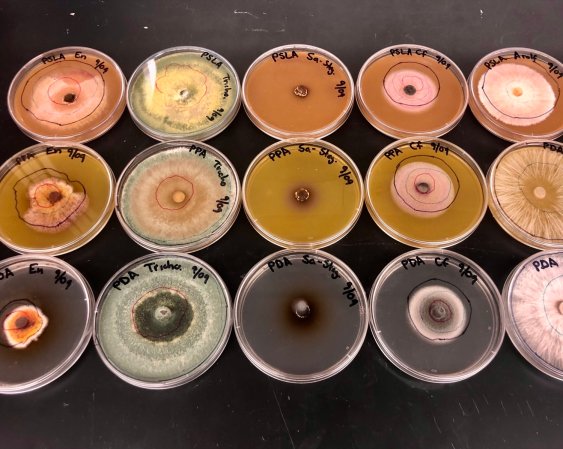

Getting rid of the buggers that crowd your bananas and melons might seem like a good idea at first glance. However, Ryalls warns that these agricultural pests contribute greatly to the world’s ecosystem. As nature’s clean-up crew, fruit flies help decompose rotting fruit, releasing nutrients for plants, bacteria, and fungi to use. They also serve as food for other animals like birds and spiders. Lastly, they are a common insect model used in biomedical research and have contributed to countless neuroscience and genetic discoveries.

Fruit flies are not the only ones feeling the effects of air pollution. Knaden says he has seen dangerous ozone levels affecting flower volatile compounds, which are used as cues for pollinators. His 2020 study found moths were less attracted to flower odors from plants exposed to the gas, resulting in less pollination.

“Insects are on the decline, and we thought it was from pesticides and habitat loss,” says Knaden. “It seems there are more screws we have to turn, one of them being air pollutants.”