We’re officially living on a planet with an atmosphere no previous human being has ever experienced. You’ll probably be able to say the same thing tomorrow.

Carbon dioxide levels recorded at the Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii reached 415 parts per million on Friday. Not only is that the highest number the observatory has recorded since it first started analyzing atmospheric greenhouse gases in 1958, but it’s more than 100 ppm higher than any point in some 800,000 years of data scientists have on global CO2 concentrations.

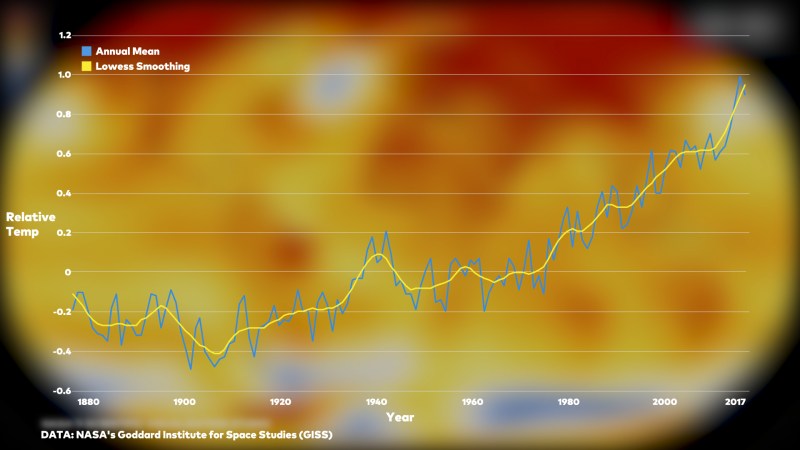

This means levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere are now nearly 40 percent higher than ever in human history. And because the measurement directly correlates with things like global temperature and ocean acidification, this record concentration is further proof that humans are changing the environment at an unprecedented rate.

While it’s true that atmospheric carbon levels (and, by extension, global temperatures) have fluctuated a great deal throughout Earth’s geologic history, they’ve never done it this quickly. And they’ve never come close to current levels in the nearly 1 million-year snapshot of atmospheric data scientists have taken using the Mauna Loa Observatory and miles-deep ice cores from the poles. If there’s one graph that shows how alarming carbon emissions really are, it’s the one that illustrates their findings:

For nearly a million years, carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere have maintained an average of about 280 ppm, not going above 300 ppm or below 160 ppm. Global warming (and cooling) trends have played out on thousand-year time scales. The latest human-caused warming event is occurring over just a couple of centuries, which is so quick in comparison that the trend line appears vertical as it approaches today.

The last time these levels reached 300 ppm, Homo sapiens didn’t even exist. It’s believed that modern humans evolved between 300,000 and 200,000 years ago, tens of thousands of years after that prehistoric maximum. Our ancestors lived through several warming and cooling periods as they progressed, developing modern practices like farming after the end of the last Ice Age about 15,000 years ago. Global warming did occur at this point, but at a much slower rate than it is now.

In the late 18th Century, coinciding with the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in Europe, atmospheric carbon skyrocketed as humans began burning fossil fuels, emitting unprecedented amounts of greenhouse gases. We know this because ice cores taken from the Antarctic ice sheet have been preserving the greenhouse gas concentrations of the atmosphere for hundreds of millennia. When snow falls on the ice sheet and compacts into ice, it traps air, essentially taking a snapshot of the atmosphere at that moment. Scientists unearth these air bubbles by extracting sometimes mile-long cylinders of ice, analyzing the concentration of greenhouse gases in the layered air bubbles.

By the time the Mauna Loa Observatory began observing greenhouse gas levels directly from the atmosphere 60 years ago, the concentration was already at 315 ppm. In 2013, these levels exceeded 400 ppm for the first time in human history.

Are humans really the cause of this carbon uptick? The answer is a clear, resounding yes. Not only does the upward trend directly correlate with the start of the Industrial Revolution, but based on tracked data on human emissions and our understanding of the rate at which nature absorbs some of those emissions (mainly through the oceans and photosynthesis), there’s an increasing amount of leftover carbon dioxide in the air that only our activities can account for.

Human emissions have sent atmospheric carbon dioxide levels on a runaway rise, increasing the average concentration nearly every year. But given the disastrous effects of the warming this causes, this new record is nothing to celebrate.