As the Greenland ice sheet melts due to climate change, a new study in journal Environmental Letters suggests, pollution trapped inside could ooze back into the environment. But microbes that have evolved to chow down on such toxins could help us out.

Despite the Arctic’s pristine image, pollution still makes its way to our most northerly latitudes. Earlier this year, researchers reported that even our plastic waste is clogging up the Arctic seas.

Similarly, persistent organic pollutants including mercury, which are released from coal fired power plants, and polychlorinated biphenyls (better known as PCBs) also end up in the Arctic, where they lurk inside the snow and ice on glaciers. PCBs were once widely used as a flame retardant, but were phased out in the 1980s as research found that they were harmful to human health and take a long time to break down. As the ice sheets melt, they release this trapped pollution back into the larger environment, raising questions about how local ecosystems will handle the influx.

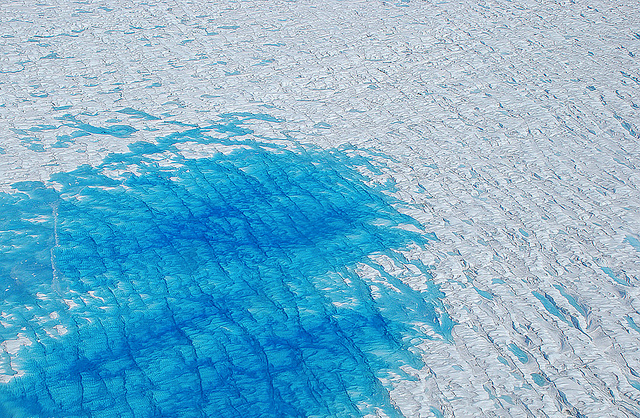

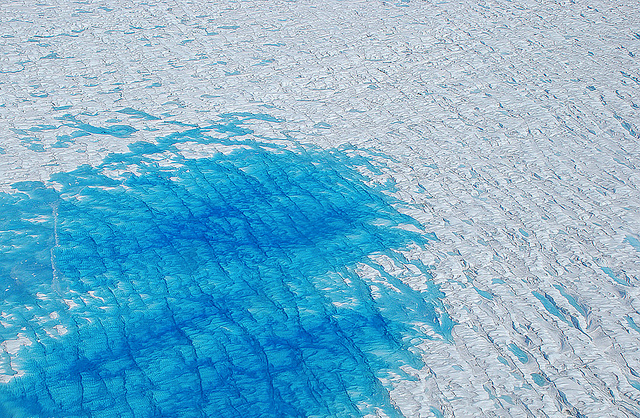

In the summer of 2013, researchers from the Technical University of Denmark, the University of Copenhagen, and Charles University in the Czech Republic headed to the Greenland ice sheet—660,000 square miles of ice that cover 80 percent of the island nation—to figure out just how bad this toxic melt could be. The Arctic is melting faster than the rest of the planet, providing insight into what changes the rest of the planet can anticipate as the climate warms. As the ice sheet (which rests on land) melts, it raises global sea levels, triggering broader shifts in the weather system.

Once in Greenland, the researchers took samples of cryoconite, a powdery windblown dust made up of microbes, soot, and small bits of rock that builds up on snow glaciers or ice caps, at five different locations on the ice sheet. They ran genetic analysis on the microbes found in the cryoconite, looking for signs that the microbes could resist or even degrade known Arctic contaminants. At least some of the microbes they found had the ability to break down some of the contaminants. When they compared the DNA of microbes in more contaminated areas versus those in less contaminated areas, they found that both sets contained the genetic profiles they’d need to fight off pollutants.

“The microbial potential to degrade anthropogenic contaminants, including polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), and the heavy metals mercury and lead, was found to be widespread, and not limited to regions close to human activities,” says Aviaja Lyberth Hauptmann, a Greenlandic scientist based at The Technical University in Denmark and lead author on the study.

“It’s potentially good news that degraders are found in the melting ice ecosystem,” says Ross Virginia, Director of the Institute of Arctic Studies at Dartmouth University, who was not involved in the study.

This isn’t, however, a carte blanche to pollute as much as we want with the expectation that Arctic microbes will clean up the mess. Because microbes generally develop resistance to a pollutant because of close proximity to that pollutant, the fact that microbes far from contaminated habitats had the same genetic resistance as those flourishing in the midst of toxins suggests that from a microbiological perspective, that the contaminants are everywhere. Greenland is really not pristine.

At the same time, it isn’t clear just how much pollution is trapped in ice sheets, how much (or how quickly) that pollution will be released over time, or how much pollution the microbes will actually be able to break down. All of those questions remain to (hopefully) be answered by future research.

In other words, it’s good news that some microbes are adapting to survive—and fight—our pollutants. But that doesn’t mean we should continue to create a world where they need to do so.