Twice as many people got antibiotic resistant infections in 2013 than we thought—but stay with us, we promise this is a good thing. Today, more than 2.8 million people get infected and upwards of 35,800 people die each year. Here’s the good news: that number has come down by about 18 percent in the last six years.

It was back in 2013 that the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) released its first report on the threat of antibiotic resistance and kicked off a whole slew of initiatives to try to combat the problem. At the time, though, we didn’t have great data on exactly how many cases or deaths any given kind of bacterium was causing. Now we know the CDC’s estimates were way off. But luckily, some of the resulting interventions appear to have had a real impact. A 28-percent drop in hospital deaths due to antibiotic resistant infections is the main driver behind the decrease, says Michael Craig, a senior advisor at the CDC’s Antibiotic Resistance Coordination and Strategy Unit.

Still, it’s not all good news. We may have made a small dent in the number of annual cases, but there are still hordes of microbes out there, and they’re constantly evolving to survive our drugs. The CDC’s latest report adds five new species of bacteria to the “urgent threats” list.

Historically we’ve used antibiotics pretty recklessly, and since bacteria are exceptionally good at transferring bits of genetic code to one another (they can literally shuttle segments between them to share newfound adaptations) they’ve rapidly developed the ability to evade even our best drugs.

To combat these tiny invaders, the CDC has had to take a wide variety of approaches. Collecting more (and more detailed) data—then sharing that info widely with researchers across the US and the world—has been a major component. That makes it easier to quickly identify newly resistant strains and change tacks if needed. As of 2018, the CDC’s lab network was detecting resistant germs worthy of investigation about once every four hours.

But avoiding resistance in the first place is even more crucial. Whenever someone takes antibiotics, they’re exposing microbes to our precious, life-saving drugs—and giving those bacteria a chance to adapt. The more infections we can prevent, the fewer opportunities bacteria have to become resistant to our treatments. And that means focusing on sanitation and access to safe drinking water worldwide, as well as investing in vaccines. “vaccination is the most powerful tool we have to eliminate disease,” says Robert Redfield, director of the CDC. It also means using antibiotics less often, both in humans and in animals.

So far these actions seem to be working, but 18 percent is still a pretty small chunk when millions of resistant infections are afoot. We still have a long way to go. The report notes we still need better data on antibiotic use and better antibiotics themselves, since so many germs now resist even our strongest medications.

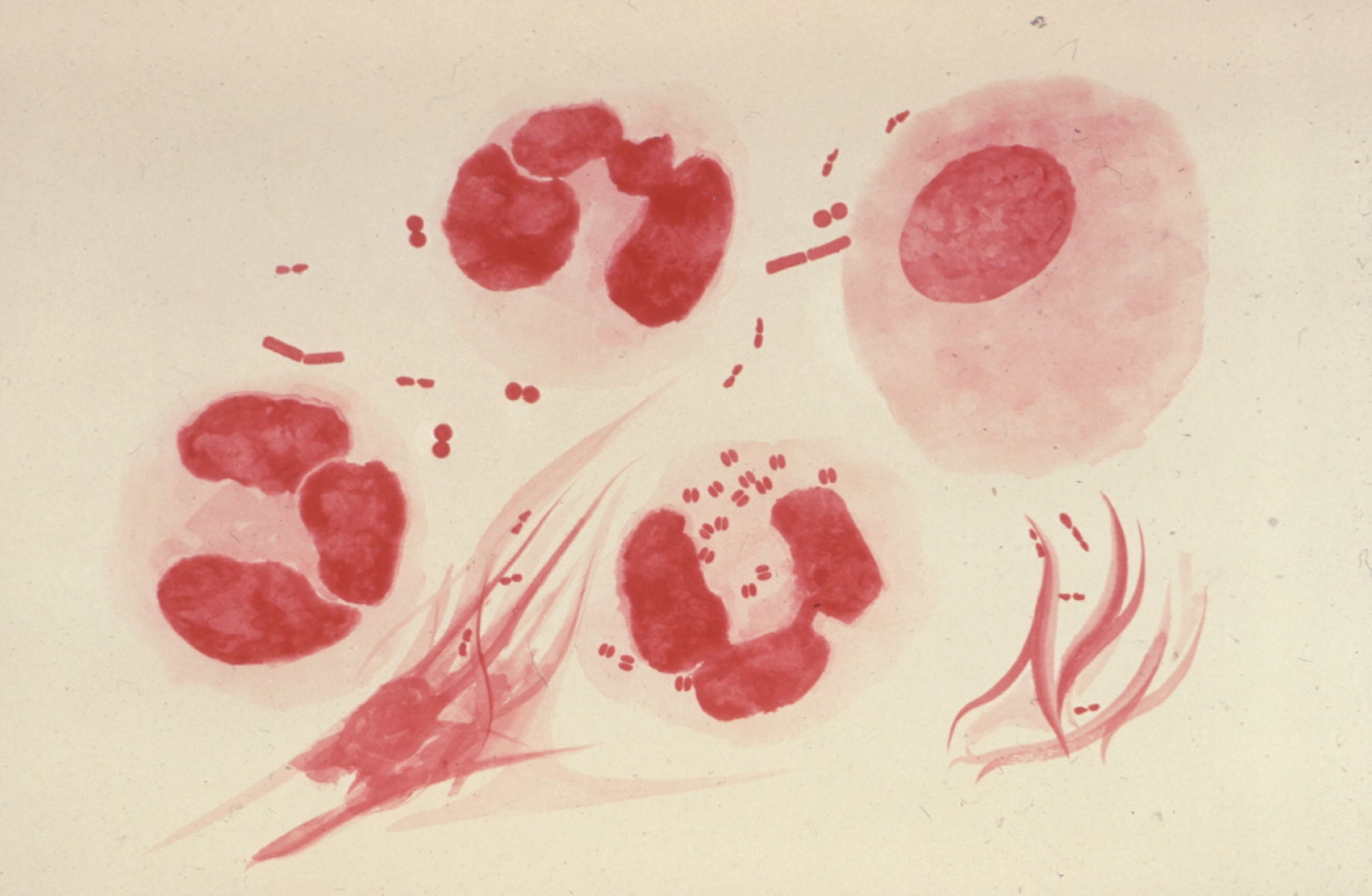

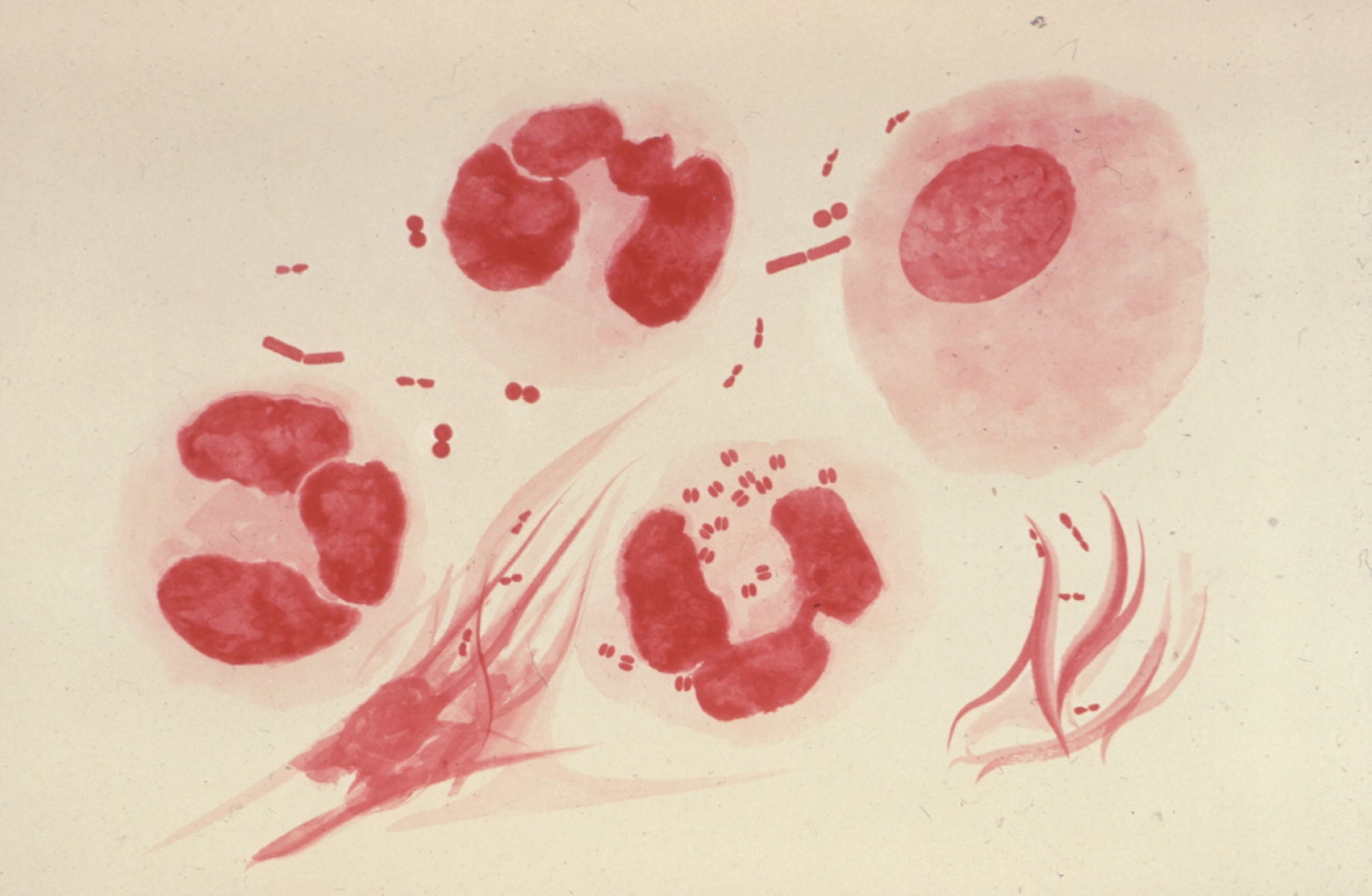

Five microbes in particular—carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter, Candida auris (which is actually a fungus), Clostridioides difficile, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, and drug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae—are on the urgent list because there are so few options left to treat them effectively. N. gonorrhoeae, which you may know better as simply gonorrhea, is now resistant to all but one class of antibiotics. Some lines of Enterobacteriaceae are immune to nearly all our drugs.

Resistant forms of Candida auris, a type of yeast, emerged on five continents at the same time. “Candida auris is one of the greatest contemporary examples of the challenge of antibiotic resistant infections emerging,” says Craig. “It’s a pathogen that we didn’t even know about when we put out the last report, and since then it’s caused a lot of deaths.” It’s unclear how or why C. auris emerged so quickly and in so many spots simultaneously, but the CDC and others are working to figure it out.

In the meantime, there’s a lot of work to be done—and you have a role to play, too. Doctors may be the ones with the power to prescribe antibiotics, but oftentimes patients request them first. It’s natural to want something to fix your ailment, but antibiotics are not always the right solution. Craig’s advice? “Never ask for an antibiotic if you’re unwell and think you need one. Ask, ‘what can make me feel better?’ Because sometimes what can make you feel better is not an antibiotic.”