For the first time researchers have used the combined brainpower of several rhesus monkeys to move a digital arm and complete various tasks with it, according to a study published today in Scientific Reports. If such a connection were possible in humans, we might be able to solve problems far better than any individual alone.

Researchers have known for a long time that brains have a tendency to sync up. When two people are tasked with the same activity, neurons in their brains start to fire at the same speed and in the same place, even if the people weren’t instructed to cooperate. No one really knows why this happens, but it’s a well-observed phenomenon—our brains are naturally inclined to cooperate with one another.

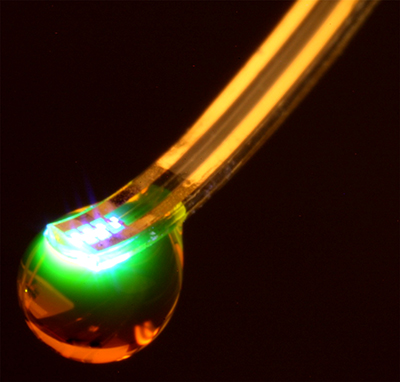

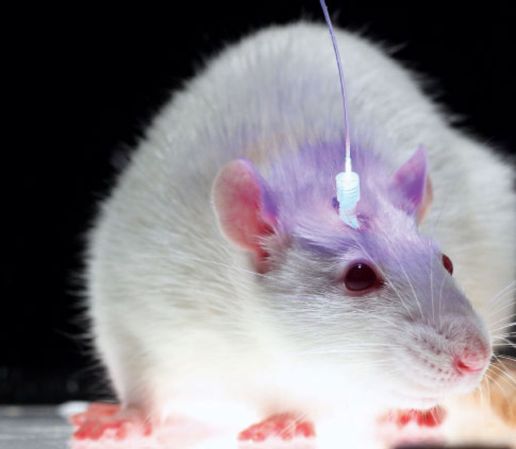

The researchers behind this study knew that the same held true for monkeys, and they wanted to see how this convergence could be applied to the brain-machine interface. In the study, they sat groups of two or three monkeys in separate rooms in front of a computer screen. Each of these monkeys had electrodes implanted in the parts of their brains associated with motor skills and somatosensation, the sense of where the body is positioned in space. The monkeys all shared control of the digital arm, able to move it along various axes so that, together, the monkeys could complete a common task of moving the arm towards a circular target on the screen. Once they achieved that, the researchers gave them juice as a reward. They first learned to move the arm with a joystick, then the researchers hooked up their brain implants to control the arm with just their minds.

Over the course of several weeks, the monkeys got much better—and faster—at working together. Collecting data from the monkeys’ brain implants, the researchers found that more neurons fired when more monkeys were working together, and that their neurons were lighting up in the same parts of the brain.

This type of neurological collaboration in humans could be useful for tasks where more minds are better than one, such as a surgery in which different members of the surgical team control a different tool, New Scientist suggests. And though that reality is still pretty far away, studies like this one indicate that it could happen much more quickly than previously thought.