As a courtesy to bug-phobes, some of the more lurid images in this post will be hidden until and unless you press this button.

SHOW

Happy Halloween! If you’re celebrating this year, which apparently three-quarters of Americans are, odds are you bought at least one thing with a scary spider or a scary bat emblazoned on it. But what do you know about these animals?

Did you know that spiders have personality, for instance? Or that bats are the reason we have tequila? Or that spider venom is actually a great painkiller? Spiders and bats are awesome, and we should celebrate them more than one day a year! Here are some reasons why.

**Bats have social networks just like us. **

Bat colonies can contain thousands or even hundreds of thousands of individual bats, hanging out together to hibernate during winter and roosting together in the summer. This spring, researchers found they maintain intricate social networks among these groups.

In the summer, when female bats give birth to their pups, they form smaller subgroups called maternity colonies. The same bats hang out together for long stretches of time, and raise their young village-style, with even smaller groups of associated bats hanging out together. Bats benefit from these relationships by keeping themselves warm, slowing the spread of disease, and helping each other locate suitable roosts, biologists say.

Rather than choosing one cave like they do in winter, summering bats will move among different trees across dozens of acres. Bats from each colony will use only certain trees, which helps colony-mates to find each other.

Bats play a major role in our food supply.

In this country, we don’t eat them, unlike some communities in equatorial Africa (where the Ebola virus emerged; it is thought to have come from bat meat). But bats are important for our food supply. Some bats snack on insects that do terrible things to our crops and our trees. Other bats give us crops directly.

Without bats, pests would gobble up cotton, corn, soybeans and other crops that we use for feeding and clothing ourselves. Bats also dine on insects that kill trees, like the invasive emerald ash borer.

In the southwest, bats give us mangoes, bananas, guavas, agave and many other fruits. They drink nectar and pollen from these plants, pollinating them and allowing fruits to grow. Without bats, we wouldn’t have tequila.

Vampire bats can help cure diseases

Despite what the movies want you to believe, they don’t drink human blood; mostly they take some sips from cattle and other livestock, after making such tiny incisions the animals don’t even notice. But vampire bats can help humans with blood pressure problems and blood clots.

Proteins in their saliva — including one called, for real, Draculin — helps thin blood so it can flow more freely. This can help break up blood clots, which can lead to stroke.

Last summer, scientists found some more novel anticoagulants in vampire bat spit, including one that causes small arteries to dilate. This could be exploited to treat high blood pressure, scientists say.

Spiders are natural pest fighters.

You’ve probably heard how honeybees are collapsing, posing a threat to bee-pollinated crops across the U.S. (about 90 percent of flowering crops, actually). Research on this is still very active, but many scientists point to pesticides as a key reason for bee problems. Spiders can help, it turns out.

This summer, scientists reported a new type of pesticide made from the venom of Australian funnel-web spiders. It contains a toxin that attacks the central nervous systems of pests like beetles and aphids, but doesn’t affect honeybees.

And spiders themselves help farmers out. Just like bats, they eat pests that would otherwise destroy our crops. “If spiders disappeared, we would face famine,” Norman Platnick, who studies arachnids at New York’s American Museum of Natural History, told the Washington Post this summer. About 20 percent of the spiders that live in this country are found in agricultural land, which includes about 615 different species.

Tarantulas can help scientists study our brains.

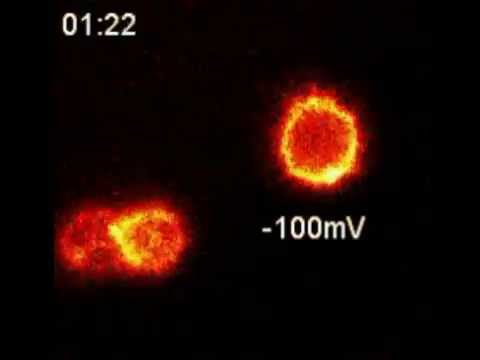

To study electrical activity in the brain, scientists usually have to modify some genes to make them fluorescent, so they can watch proteins switch on or off. But this week, researchers at the University of California at Davis found they could do it with spider venom instead, and no genetic modification.

They developed a cellular probe that combines a toxin from tarantula venom with a fluorescent protein. The cell binds to a type of potassium ion channel, and lights up when the channel shuts off and dims when it’s activated. By watching the glow, scientists can observe electrical activity in neurons, and study ion-channel problems that can lead to epilepsy and other disorders.

Spider venom dulls our pain.

One of the reasons people fear spiders is that we’re afraid they’ll bite us, which will hurt or poison us in some way. But spider venom can actually be a potent painkiller, not pain-causer.

In a study published this past winter, scientists screened 100 different spider toxins and found a protein from one particular spider, the Peruvian green velvet tarantula. This compound blocks activity in neurons that transmit pain, the researchers say. Further research could turn this toxin into a painkiller on par with drugs like morphine.

So tonight as you celebrate Halloween, remember the mascots on all your cupcakes and decor aren’t just scary — they’re pretty cool all year round.