While the Atlantic Hurricanes Florence and Michael have rightfully gotten most of our attention this season, climate conditions in the Pacific are churning out one storm after another. We’ve seen a whopping 21 named storms in that region so far this year, but even that sheer number does no justice to the intensity of this hurricane season. This Pacific hurricane season could likely end up being the most intense one that meteorologists have ever recorded.

The Pacific hurricane season covers all storms that form between the western coast of North America and 180°W, which is also known as the International Date Line. The eastern Pacific basin stretches from the western coast of North America to 140°W longitude. The central Pacific basin, which covers Hawaii, stretches from 140°W to 180°W. Meteorologists and climatologists often combine the two basins since most of the storms that cross through the central Pacific originated in the eastern Pacific.

Storms that form west of the international date line are still tropical cyclones, but instead of being called hurricanes, they’re known as typhoons. Typhoons are tracked separately from hurricanes in the central and eastern Pacific because of geopolitical reasons and the fact that storms in the western Pacific are influenced by different factors than storms in the rest of the ocean.

The eastern and central Pacific basins have seen an incredible 20 named storms so far this year. The season began with Hurricane Aletta’s formation on June 5 and continued through Tropical Storm Tara in the middle of October. Another tropical depression had a high chance of developing into the next named storm, Willa, by the publication of this post.

12 of those named storms became hurricanes, and nine of those storms strengthened into a category four or five at one point during their lifespan. Nine storms with winds reaching category four or five status on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale is a record for the most storms we’ve ever seen achieve that strength during one Pacific hurricane season.

The sheer energy released by these storms places this year in record territory. Meteorologists measure the strength of a hurricane season through Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE). ACE measures the energy produced by a storm by calculating the maximum sustained winds of the storm over its lifespan. The average ACE value for the eastern and central Pacific basins combined is about 121. The ACE generated by this year’s storms through October 16 is 294—more than double what you’d see in an average year and putting it just shy of the most intense year on record. The ACE generated by the next tropical cyclone, should it develop, will give this season the dubious distinction of most intense on record.

For context, the entire Pacific—from Asia to North America—is traditionally more active than the Atlantic basin. The eastern Pacific alone typically sees about 15 named storms in an average year compared to just 12 over in the Atlantic. The Pacific is usually busier than the Atlantic because sea surface temperatures are warmer and there are fewer factors present—such as dry air or wind shear—to inhibit the development of storms. The developing El Niño in the eastern Pacific this year is also likely boosting the development of storms and helping them reach their full potential.

Unlike the Atlantic, the list of storm names in the eastern Pacific includes the letters X, Y, and Z to account for the heightened activity. It would be a heavy lift for this hurricane season to exhaust the English alphabet and continue into the Greek alphabet—which has only happened once, during the 2005 Atlantic hurricane season—but it’s not a completely implausible scenario at this point.

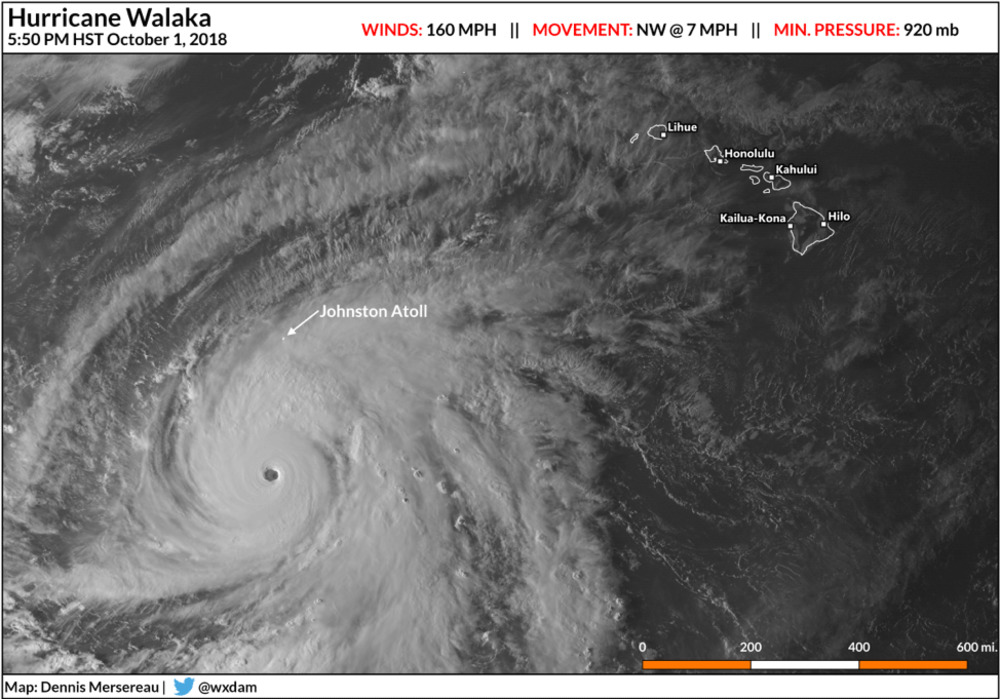

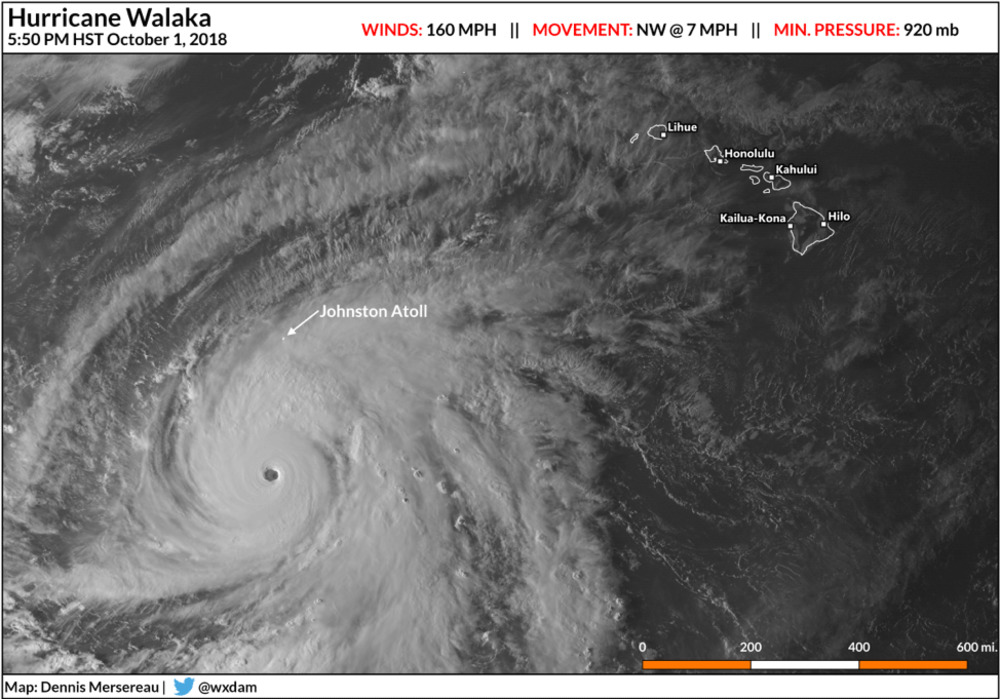

Despite the number and strength of storms so far this year, relatively few have threatened land at full strength in the central or eastern Pacific. Hawaii faced the greatest tropical threats this year, feeling the effects of Hurricane Lane in August and Tropical Storm Olivia in September. Lane produced the second-highest rainfall total ever recorded during a tropical cyclone anywhere in the United States, dropping 52 inches of rain on the Big Island as it passed just south of the island chain. Hurricane Walaka, the only storm to actually form in the central Pacific this year, made a close brush with Johnston Atoll in October before heading out to open waters.

Thankfully, prevailing winds across the region usually sweep these storms westward, sending them out to sea where they perish in cooler waters, but there are notable exceptions. Storms hit or brush Mexico fairly regularly and can cause significant wind damage to coastal communities and produce life-threatening flash flooding and mudslides across inland mountainous areas. Six storms this year either made landfall in or closely brushed Mexico. Luckily, all of those storms were tropical storms or weaker, and they were predominately rainmakers. The remnant moisture from Hurricanes Bud, Rosa, and Sergio produced flooding rains when they moved into the southwestern United States.

The Pacific hurricane season continues through the end of November.