On April 15, the World Health Organization (WHO) posted an emergency disease outbreak alert that was not strictly about the COVID pandemic. Over the course of the past two weeks, the medical arm of the United Nations has gathered more than 70 reports of acute hepatitis in the UK, Scotland, and Spain. Yearly, millions of people are diagnosed with acute hepatitis around the world. But these cases alarmed WHO officials because they were in kids between the ages of 1 months and 13 years.

The young patients shared a similar list of symptoms, including jaundice, vomiting, diarrhea, and gastrointestinal pain. At least six experienced complete liver failure and had to undergo an organ transplant. But the source of the disease is still unknown, the WHO stated. Laboratory results ruled out Hepatitis A, B, C, D, and E—the viruses that typically cause liver infections.

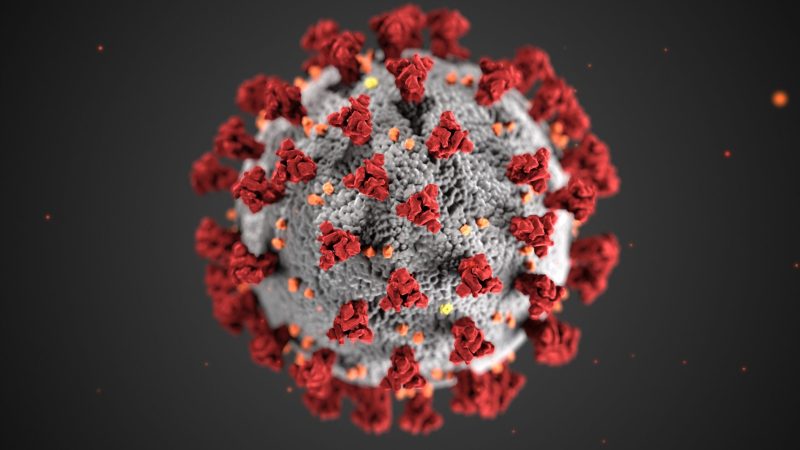

The tests did, however, detect SARS-CoV-2 and adenovirus in several patients. Children are especially susceptible to adenoviruses, which cause sore throat, bronchitis, pink eye, gastroenteritis, and more. The WHO noted that the pathogens have been circulating in the UK, on top of continued COVID outbreaks.

While the WHO alert only covers Western Europe, the US might be on the brink of a pediatric hepatitis surge. Also on April 15, the Alabama Department of Public Health shared that it had identified 9 cases of the disease in children under the age of 10. The first example dates back to November 2021 (the WHO’s earliest record was January 2022). All of the patients tested positive for Type 41 adenovirus, and two required full liver transplants. The news release didn’t mention any presence of SARS-CoV-2.

Although the two agencies haven’t explicitly linked their cases together, the Alabama Department of Health stated that it’s “discussing similar cases of hepatitis potentially associated with adenovirus with international colleagues.” It also wrote that it’s working with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to develop “a national Health Advisory looking for clinically similar cases with liver injury of unknown etiology or associated with adenovirus infection in other states.”

[Related: The deadly combination behind the surge of ‘superbug’ fungus outbreaks]

So far, the mysterious disease hasn’t led to any deaths in the US or Europe. But the WHO did strike a cautionary note in its alert. “Given the increase in cases reported over the past one month and enhanced case search activities, more cases are likely to be reported in the coming days,” it stated last week. It didn’t, however, recommend travel restrictions to or from countries experiencing the sudden uptick of childhood hepatitis.

None of the young patients in Alabama had other underlying illnesses, Karen Landers, a district medical officer, told STAT News. “Seeing children with severe [hepatitis] in the absence of severe underlying health problems is very rare,” she continued. “That’s what really stood out to us in the state.”

The STAT News article also explains that while an adenovirus, not a coronavirus, likely triggered the liver infections, SARS-CoV-2 might have played a secondary role in the outbreaks. Lockdowns and universal mask use over the past two years have kept some infants from encountering common germs that they would otherwise gain immunity to. This could result in more severe reactions to adenoviruses, which can easily infect people via skin or surfaces and are resistant to many disinfectants.

There are a few ways to protect kids from these infectious agents. As with COVID, teaching them to wash their hands with soap and water for at least 20 seconds, touch their face less, and share symptoms when they first feel sick can help reduce transmission. On the community level, families, schools, and physicians should keep a close eye on cases and share any notable patterns with local health authorities. Potential outbreaks will then get reported up to policy-making agencies like the WHO and the CDC, who can keep the public informed.