Austin Heap is an unlikely international saboteur, but last summer the San Francisco–based Web developer staged a digital coup in Iran shortly after presidential-election protests took place there. Heap’s Haystack software, smuggled into the country on USB flash drives and passed secretively from citizen to citizen, allowed Iranians to get around the government’s notorious Internet filters and, for the first time, freely explore and communicate on the Web.

This month marks the anniversary of the protests. After Tehran banned foreign journalists, civilians’ illicit Web posts became the only source of independent information. Most famously, YouTube hosted two graphic videos of a young woman being shot and killed while en route to an anti-government rally. But the government’s filtering tech meant the videos couldn’t be viewed inside the country.

Haystack, produced by Heap’s nonprofit Censorship Research Center, is one of the first beneficiaries of a new U.S. government initiative to foster uncensored access to the Web abroad. In March, the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), which administers foreign trade sanctions, revised its laws to allow the export of Internet communications services, including chat and social-networking software, to Iran. OFAC also granted Heap special permission to continue distributing Haystack there. By midsummer, he expects thousands of Iranians to be able to bypass the country’s Web filters.

“The Internet is what connected me to the rest of the world when I was stuck in Ohio growing up,” Heap says. “I don’t know who I would be without it. When I heard what the Iranian government was doing, I figured if we can help, we should.” So he partnered with Web developer Daniel Colascione and, based on networking documents leaked to them from an Iranian source, they used their knowledge of network architecture and cryptography to create a workaround.

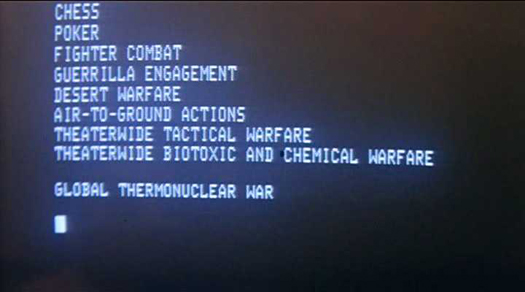

Iran is a tech-savvy foe. According to news reports, a joint venture between Nokia and Siemens provided Iran with the capability to conduct surveillance of Internet traffic. Iran’s software uses a sophisticated process known as “packet sniffing.” A tiny segment in the code of any Web page, e-mail or IM conversation contains identifying characteristics—like a virtual fingerprint. The filter scans for these packets, and if it detects that a person is trying to view a prohibited Web site, such as BBCPersian.com or Facebook, it will block the request and redirect the person to an official error page. Haystack subverts that process by faking the packets so that the digital trail will appear as if the person were visiting an authorized site. Then the encrypted connection to Haystack’s servers will allow the real request to go through, and BBCPersian.com loads as it normally would.

Haystack is currently tailored to work specifically for Iranian users, but Heap says he has received requests from human-rights organizations in China and Cuba, countries that also use complicated online filtering, to adapt the technology for use there. For instance, the software could connect Chinese users to Google, which recently pulled out of mainland China over censorship disagreements. This highlights a less humanitarian benefit of getting the rest of the world online: More people using search engines, like Google, or visiting ad-driven sites could boost those companies’ profits.

Most likely, OFAC will wait to see how Haystack and other programs fare in Iran before loosening restrictions that ban software exports to other countries. Heap will be ready. “This is about making sure that the first open, global communication network in history continues to be used by the people, not against them,” he says. “It’s a right every person deserves.”

![How Iran Censors The Internet [Infographic]](https://www.popsci.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/18/VPUTTRWUQW2ZKSJPN5XC2LHU5U.jpg?quality=85&w=525)