If you’re immunocompromised and happen to find any bird or bat poop in your barn, you’d better hose it down instead of sweeping it up. Brushing away the poop could unleash potentially dangerous fungus into the air, according to Andrej Spec, an infectious disease physician and researcher at Washington University in St. Louis.

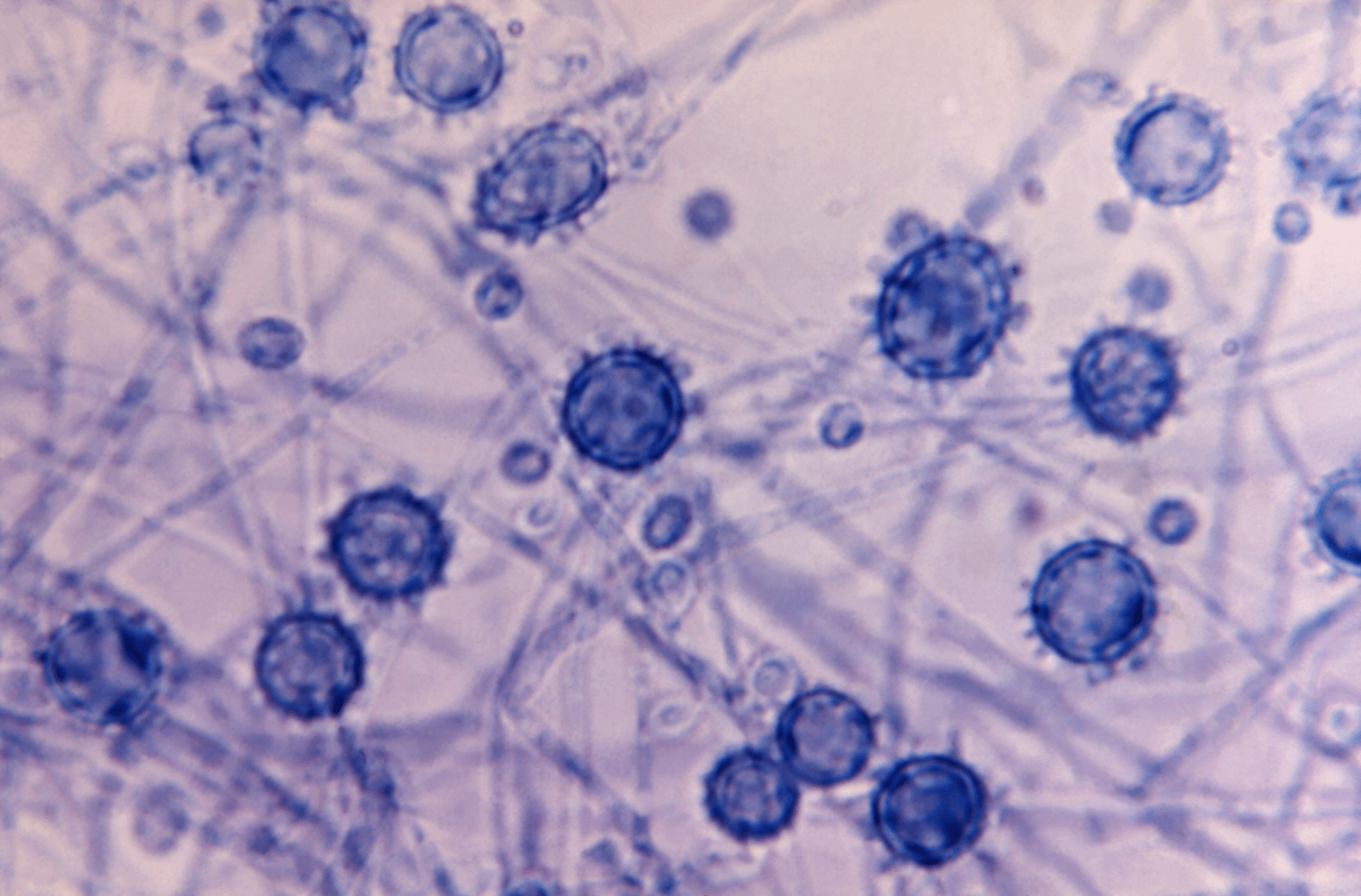

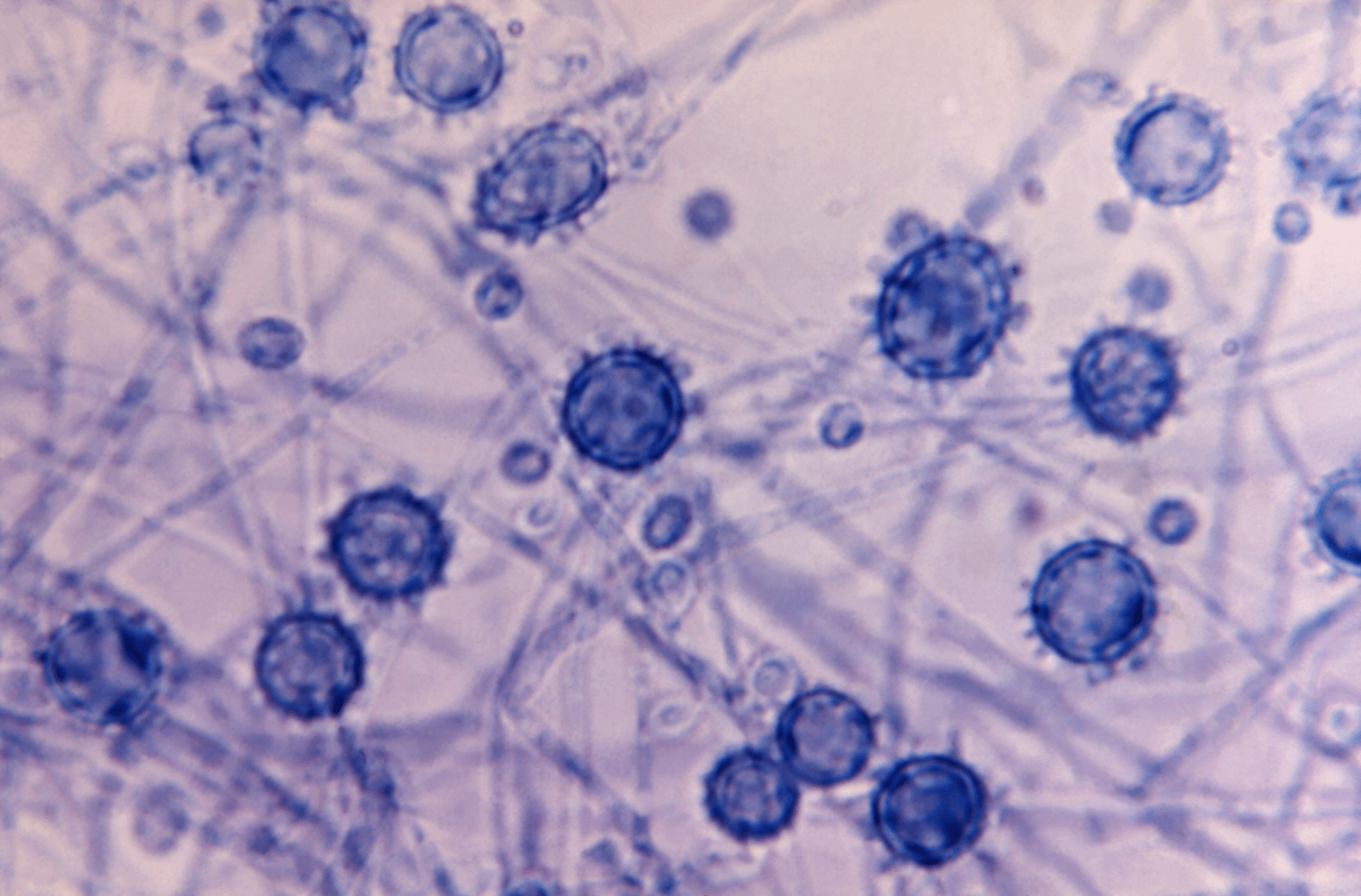

When certain species of soil fungi become airborne, people could unwittingly breathe in the spores. Once in the lungs, the fungus can infiltrate the body and cause disease, like histoplasmosis, a lung infection caused by inhaling spores from the Histoplasma fungi. The disease, commonly associated with bird and bat droppings, had primarily been endemic in the Midwest, particularly around the Ohio and Mississippi River Valleys, where Histoplasma commonly grows. But now, histoplasmosis has been diagnosed at significant rates in at least one county in 94 percent of US states—an expansion that has been linked to climate change.

This spread is not limited to Histoplasma. Two independent reports published this month suggest that Histoplasma and additional disease-causing soil fungi—Coccidioides and Blastomyces—seem to be spreading outside their historic zones. Coccidioides, the fungus that causes coccidioidomycosis (commonly known as valley fever), prefers to dwell in arid environments of the Southwest, while Blastomyces, the fungal agent of blastomycosis, has commonly resided in Southern and Midwestern states. Understanding where soil fungus is on the rise and why is important for physicians like Spec who worry these fungal diseases might be slipping under the radar.

“Many of us have been very concerned, because in order to diagnose these most of the time, you have to think ahead,” says Spec, co-author of the study published on November 16 in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases. “So many people outside of the endemic areas are not being diagnosed, because nobody thinks to diagnose them.”

[Related: This deadly fungal disease could use climate change to mobilize]

Researchers and clinicians have largely depended upon fungal distribution maps from the 1950 and 1960s. When men were drafted into the US military, Navy researchers tested their reactivity to fungal antigens as part of their physical exams—methods that Spec says would be “impractical or unethical” today. However, the data is considered outdated, and is not representative of certain populations.

In his analysis, Spec and his team looked at how many people were diagnosed with infections caused by the three fungi and where they were located. They drew the recent numbers from a dataset created between 2007 to 2016 which included over 45 million people enrolled in Medicare, the US government health insurance program for people over the age of 65 and some younger people with disabilities. Then, the team compared the modern distributions to the older, out-dated maps created in the 1950s and 1960s.

The study found cases were spread across the country, with at least one county in 94 percent of states reporting histoplasmosis cases at significant rates, 78 percent of states reporting for blastomycosis, and 69 percent of states for coccidioidomycosis. With the new distribution data revealing a much geographic wider range, it’s likely that most people have inhaled spores from one of the fungi, according to Spec. But disease might only occur when “you inhale either too much, or you inhale them at the wrong time, and your [body’s immune system] doesn’t handle them,” he says.

The elderly and the immunocompromised are particularly at risk of infection from these fungi. The infection starts in the lungs and often presents symptoms similar to other respiratory illnesses—coughing, shortness of breath, potentially fever and chills. However, in severe cases, the fungus can spread to other parts of the body, including the skin, bones, brain, and intestines. Depending on the species of fungus, severe cases can even manifest as meningitis or brain abscesses.

Spec says there are several reasons why the fungi seem to have spread outside their historical zones. One leading culprit could be climate change; shifting temperatures and environmental conditions could make the soil more habitable for the fungi in new areas. A study in 2019 even predicted where the fungi might spread with climate change, and the projections for Coccidioides in the next several decades look scarily similar to the map Spec’s team developed.

Human migration, specifically for valley fever, could have also contributed to the geographic spread of the fungus. Another possible cause for the growing range could be due to a lack of awareness and understanding of the fungi in the new locations.

[Related: Is it flu or RSV? It can be tough to tell.]

A review by researchers at the University of California, Davis gave similar warning about the prevalence of fungal diseases. Published on November 22 in Annals of Internal Medicine, the authors write that the fungi are probably much more widespread than we think. “The organisms are probably much more widespread than we originally thought,” George Thompson, author of the review study and UC Davis professor, said in a press release. “There is an increasing likelihood that clinicians who are not familiar with these organisms will encounter them during their daily practice.”

One of the key takeaways from these latest assessments is that it’s important for physicians to consider fungal infections, even if the patient isn’t within a historically endemic region.

“I think the solution for a community is for us as physicians to get better at diagnosing them and better at treating them early,” he says. “Then the patients can live a more normal life.”