This article was originally featured on Hakai Magazine, an online publication about science and society in coastal ecosystems. Read more stories like this at hakaimagazine.com.

The Cook Islands’ main harbor is a small indentation in the island of Rarotonga, which is the most developed of the nation’s 15 islands, yet still the kind of place where you give directions in mango trees and neighbors, not house numbers and street names. The harbor has a few long-term residents and a lone police boat that monitors an area roughly the size of Mexico for illegal fishing by vessels from Europe, North America, and Asia. There are also vessels that transport building materials and basic food such as flour and rice to outer islands, some of them 1,200 kilometers away, where more than one-quarter of the Cook Islands’ 14,600 residents live, fish, forage, and harvest.

Visitors to the harbor include fuel tankers and a cargo ship that arrives twice a month from New Zealand to deliver almost all of the country’s groceries. These are the largest vessels that enter the harbor; cruise ships that feed the islands’ primary industry—tourism—have to anchor at sea and transfer passengers ashore in tenders. There isn’t room on Rarotonga to permanently accommodate the ships that have come to scope the potential of the deep sea for commercial mining. One came from Galveston, Texas, in February; another is returning this year from a fit-out in Wellington, New Zealand. Both can call into Aitutaki, a nearby island with a population of about 1,800, when Rarotonga’s port is occupied. The Cook Islands government began widening and deepening Aitutaki’s harbor in 2021, several months before awarding three companies licenses to explore the country’s territorial waters for polymetallic nodules. This is the official name for the lumps found on the seabed, between 3.5 and six kilometers deep, that contain multiple minerals, including manganese and cobalt, a component of batteries in cellphones, laptops, electric vehicles, and other technologies considered essential to the energy revolution. Time magazine called the nodules a “climate solution”; to Mark Brown, the prime minister of the Cook Islands, they’re “golden apples” ripe for picking.

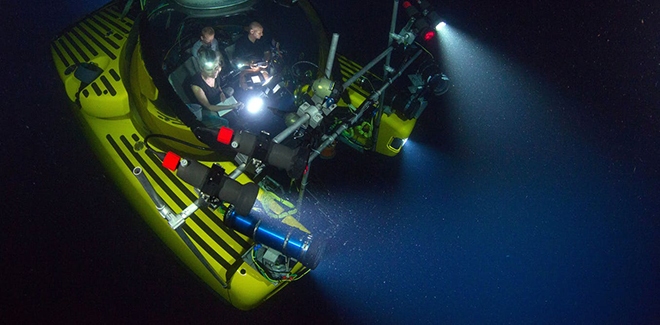

The ships are the latest and largest indicators that deep-sea mining companies have arrived in the Cook Islands. They came bearing gifts and promises of prosperity, progress, and knowledge. They arrived to drums, fire, and chanting by a man dressed in tī leaves. Vessels with millions of dollars of equipment on board unloaded their crews into an incongruous landscape: lush jungle, brilliant blue sky, trees full of flowers and fruit. The vessels are authorized to conduct research expeditions for five years. After this, the Cook Islands government will make a decision: reject mining, continue collecting data, or, in the government’s parlance, begin harvesting.

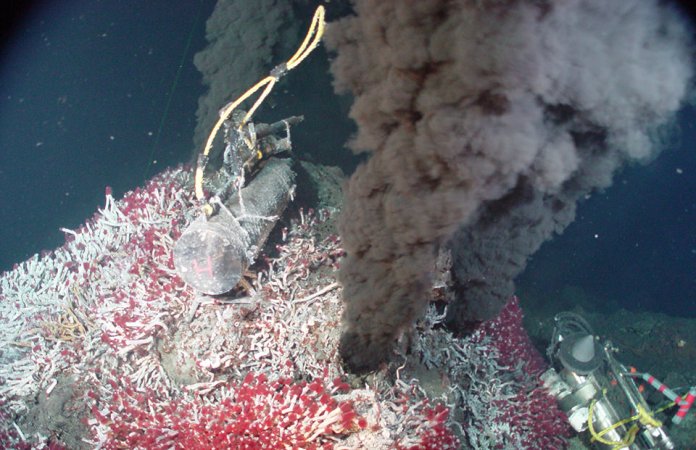

For years, there were signs that deep-sea mining was coming to the Cook Islands: speeches by politicians, public meetings, a government agency called the Seabed Minerals Authority (SBMA) that employed a handful of people. Cook Islanders had been hearing about the nodules since a scientific expedition discovered them in neighboring French Polynesia in the late 1950s, back when New Zealand still ran the country’s government. Research boats came for decades from places like the Soviet Union and Japan to study the deep-sea minerals, but always it remained too expensive to commercially extract anything from kilometers down, where the pressure is intense enough to implode submarines. Research, too, remained cost-prohibitive. After half a century of investigating the deep sea, we know more about the moon.

In 2008, the prices of manganese and cobalt spiked. Corporations courted the International Seabed Authority (ISA), an intergovernmental body in Kingston, Jamaica, created by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea to regulate access to the seabed in international waters. Already the ISA had engaged contractors to explore the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, an area of ocean beyond national jurisdiction between Hawai‘i and Mexico. Mining was finally starting to make more economic sense. Companies also began engaging with the governments of small island states that control large oceans. In 2009, the Cook Islands parliament passed the Seabed Minerals Act.

Across the sea, in other worlds, scientists raised questions. Why stage industrial operations in a place we know almost nothing about? Could waste—the sediment and heavy metals that get vacuumed off the seabed, processed aboard large ships, and returned to the ocean—enter food chains, including those that connect the ocean to the people of the ocean? What happens when we disturb the seafloor, which locks carbon in its sediments?

Still, like the deep sea itself, the industry remained largely out of public focus. In the Cook Islands, only decision-makers and the civically engaged paid attention when the Seabed Minerals Act was replaced in 2019 and then amended in 2020. Among the changes was the delegation of authority that left seabed-related decisions largely in the hands of a single person: the minister of minerals, who is currently the prime minister.

In March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic stalled the Cook Islands’ economic engine—the tourism industry that contributed 61 percent of the country’s GDP in 2019. Passenger planes and cruise ships stopped coming. Aid floated the cash economy. People returned to communal life: tending plantations on the land islanders inherit by birthright, catching fish, and bartering what they grew and caught. Despite the march of modernity, islanders still have land and sea and a deep, lived connection to both. On most islands, a cargo ship comes a few times a year. “You can’t really starve here unless you’re completely useless,” says Jason Tuara, a 45-year-old father who lives on Rarotonga and feeds his family by fishing tuna and marlin, hunting pigs, trapping chickens, and tending fruits and vegetables.

Sealed borders strengthened an already close-knit community. Elsewhere in the world, people could not gather, but in the COVID-free Cook Islands, there were more parties and sporting events than usual. Expatriates reported feeling newly embraced during that time. Tourists who were in the country when the borders closed became part of the community, too. Two of the people who got happily stuck in the Cook Islands were Greg and Laurie Stemm of Tampa, Florida. Greg had registered deep-sea mining company CIC with the Cook Islands Ministry of Justice the previous year, and in early 2020, the couple was stopping by Rarotonga on the way to a conference in Australia. “I only had a carry-on,” Laurie says, laughing.

Greg is the cofounder and chairman emeritus of Odyssey Marine Exploration, a company whose website announces it found more shipwrecks than any other organization in the world before shifting focus in 2009 to a “multibillion-dollar idea”: deep-sea minerals. Odyssey made headlines in 2019 for suing the Mexican government for US $3.5-billion over the denial of environmental permits for a seabed mining project on the grounds that the decision violated the North American Free Trade Agreement. Stranded in paradise, the Stemms made friends at yoga classes and Māori lessons with people who describe them as “lovely” and “down-to-earth.” Laurie befriended Michael Tavioni, an artist and writer, on a tour of Rarotonga she took with CIC’s in-country manager. She told Tavioni that her grandfather was a carver and she wanted to learn how to carve; he invited her to show up at 9:00 a.m. the next day. “And then I never left,” Laurie says. She registered a company called Cook Islands Traditional Arts Press, through which she helped Tavioni print a book he’d been drafting on his laptop. “It all just flowed,” Laurie recalls.

When I returned to the Cook Islands after spending the pandemic in a place that definitely did not experience a higher-than-usual volume of parties and sporting events, the “coconut wireless”—a gossip channel with a remarkably high penetration rate—was carrying stories of gifts local people had received from seabed mining companies, in particular CIC. There was unsubstantiated talk of new trucks and boats. The substantiated gifts, which appear in CIC’s application for a research license from the SBMA, are more benevolent: medical equipment used to treat COVID-19, funding for arts curricula in schools, support for Tavioni’s work.

Tavioni, 76, has a white ponytail and strong, well-researched opinions. He’s best known for carving traditional canoes. People fly to Rarotonga to learn from him. For decades, he has been writing letters to the editor of the Cook Islands News, asking the government to fund the traditional arts. He is grateful to the Stemms and all the other donors who have helped to bring his dream to life by supporting a gallery and gathering space where people can make traditional art.

Beneath the iron roof of his workshop, Tavioni tells me that for 20 years he has been advocating for the nodules as a pathway to sovereign wealth—not wealth generated by tourism, a trade in which “we dance like monkeys for other people,” nor handouts from the governments of New Zealand, China, or any other country. “We are not beggars,” he says over the tapping of the sawdust-covered student who is carving beside him.

Tavioni sees the nodules as a means of alleviating depopulation—the mass migration to urban centers such as Auckland, New Zealand, and Brisbane, Australia, that leaves homes abandoned, yards overgrown, and positions vacant for workers from Fiji and the Philippines to fill. He thinks environmentalists should pay more attention to existing problems, such as the plastic tourists contribute to Rarotonga’s only dump. Besides, he says, deep-sea mining isn’t really mining; there’s no dynamite. “They dramatize it like mining where they blow up the mountain,” he says. “No such thing. … They’re just picking [the minerals] up.”

In June 2021, the president of the Republic of Nauru, a Pacific Island nation about one-third the size of Rarotonga, sent a letter to the ISA that invoked a clause in the law of the sea requiring the completion of guidelines for mining in international waters within two years. Only countries can be members of the ISA, so companies interested in deep-sea mining have to find a sponsoring state. Nauru is a sponsoring state for Nauru Ocean Resources, a subsidiary of Canadian corporation the Metals Company, whose CEO was involved with another company that “lost a half-billion dollars of investor money, got crosswise with a South Pacific government, destroyed sensitive seabed habitat and ultimately went broke,” as reported in the Wall Street Journal. That “South Pacific government” was Papua New Guinea’s; the country now supports a 10-year moratorium on seabed mining. Since being introduced at a regional meeting in 2019, the proposal for a moratorium has gained the support of such players as Google, Samsung, Volkswagen, Volvo, BMW, New Zealand, Germany, France, Spain, a number of Pacific island nations, including French Polynesia, and more than 760 science and policy experts who warn that the impact of deep-sea mining will be “irreversible on multigenerational timescales.”

In January 2022, after nearly two years of remaining shut, the borders of the Cook Islands reopened. The following month, the government hosted a formal ceremony to celebrate the awarding of exploration licenses to three deep-sea mining companies: CIC; CIICSR, the government’s joint venture with Belgian mining company GSR; and Moana Minerals, an offshoot of Ocean Minerals, a Texas-based corporation founded by an engineer who worked in deep-water oil and gas drilling and run by a diamond miner from South Africa. After receiving their licenses, the three companies hired managers and staff, rented office spaces, and began promoting their activities in the Cook Islands. Advertising in the local paper, Moana Minerals described itself as a company focused on metals “critical to the transition to green energy, responsibly sourced from seafloor nodules.” Greg Stemm tells the camera in a video posted on YouTube: “I think everybody believes we have a climate change emergency. Do we want to wait 10 years or 15 or 20 years [to address it]? Maybe, but how much longer do we want to keep using oil and gas, keep polluting our atmosphere, and continuing to create huge climate change issues?”

At COP 27, the international climate change conference convened in Egypt in November 2022, Prime Minister Brown issued a strong statement to supporters of the proposal for a moratorium on seabed mining. In his speech, Brown took exception to the fact that the countries that had destroyed our planet through “decades of profit-driven development” were now making demands restricting use of the Cook Islands’ territorial waters. “It is patronizing and it implies that we are too dumb or too greedy to know what we are doing in our oceans,” he said. “We know what we are doing to protect ourselves and to protect our ocean.”

Applications for the exploration licenses awarded in February 2022 were reviewed by the SBMA and a licensing panel made up of government officials and foreign consultants. In 2020, the prime minister appointed seven members to the Seabed Minerals Advisory Committee to “provide a voice for the community,” according to a press release. The committee’s chair, Bishop Tutai Pere, said in a speech at the licensing ceremony that it would be a sin to leave the nodules on the seabed. In a Q&A posted on the SBMA website, Pere attributes discussion about the environmental impact of deep-sea mining to “only a fear of the untapped depth of the unknown, surrounded by sacred taboos, superstition, and lack of faith.” One member of the committee, who represents traditional leaders, applied for a job with Moana Minerals; he lit up when he mentioned the NZ $1,000 he received for spending a week at sea with the company’s scientists. (This is not a paltry sum; most workers in the Cook Islands earn less than NZ $20,000 annually.) Another member of the advisory committee isn’t sure whether the companies that are licensed in the Cook Islands have the technological capacity to access the nodules (they do); he also thinks the nodules drift here with the current, like the fish, though scientists say they formed in place, slowly accreting over millions of years.

As is the case when any community grapples with an issue, perspectives on deep-sea mining in the Cook Islands vary. Advocates ask: Why shouldn’t we gain the means to better resource the ministries of health and education so we don’t have to fly to New Zealand for medical attention and send our kids to boarding school? Shouldn’t we pursue industry so we can entice some of our people to return home from the cities? They say it’s possible to mine the seafloor responsibly.

Opponents say the risk is too high, particularly now, as climate change and overfishing alter the ocean for island people. Lawyer and former politician Iaveta Short sees the nodules as yet another opportunity for corruption and financial mismanagement. “To me, we’re heading down the same road as Nauru,” he says, referring to the phosphate mining that made the island of Nauru briefly rich. The government squandered the money on an airline, a musical, and hotels overseas, among other unsuccessful investments. The land is now 80 percent infertile. A 1999 report by the island’s government describes Nauru as “one of the most environmentally degraded areas on Earth.” Short adds: “I think we’re going to be taken to the cleaners, just like everybody else.”

There are also people in the Cook Islands who don’t agree with seabed mining but will only talk to me off the record. A few insist on meeting under cover of night. They saw what happened to Jacqui Evans, a scientist who helped draft the Marae Moana Act, which passed in 2017, creating a legal basis for the world’s largest marine protected area. She won the distinguished Goldman Environmental Prize for this work and was shortly thereafter replaced as the marine park’s director and sole employee because she wrote an internal email in which she expressed support for a moratorium on mining. Many see the risk of questioning their government as too great. The government is a significant employer; in a place where most people are related, everyone is close to someone who works for the public service. Some chiefs—who wield influence, and, on some islands, explicit political power—work for the government, too.

A lot of people just don’t have enough time and interest to study the technical information provided by the government. A leader of a new political party vying for seats in parliament describes all the minerals-related material he’s asked to read as boring. “I look at it as, oh my gosh, who has the time?” he says.

One observer in an art-filled house on a red-dirt road has the time. The man, who requested anonymity, has closely tracked the development of the deep-sea minerals industry in the Cook Islands and recognizes historical patterns reminiscent of the colonial project that occurred in the Pacific and elsewhere.

His theory triggers a range of reactions in people I repeat it to—indignation, defensiveness, anger, fear—but he discusses it unremarkably. “Well, what’s happening?” he asks. “The Seabed Minerals Authority [is] emphasizing that they’re taking a precautionary approach by doing the research, yeah? But in fact, that’s the first stage of colonization. The mining companies are going out there exploring it, and they’re going to map it. And then they’re going to extract from it.”

He sees other colonial echoes, too: “alienating scientific discourse,” the role of religion, the compradores. Comprador, a Portuguese word for “buyer,” denotes a local person who acts as an agent on behalf of a foreign organization.

As the world engages in a debate over deep-sea mining, life proceeds on the islands. Some people dream about golden apples. Others feed pigs and plant taro. Beyond the reef, the 1,347-tonne ship Anuanua Moana, which belongs to Moana Minerals, is mapping the seafloor in the Cook Islands’ territorial waters with sonar and collecting samples of the material that some describe as humanity’s only hope, the minerals needed to free us from the grip of fossil fuels. The other two license holders are working toward completing their own research expeditions, estimated to cost US $100,000 per day.

Anuanua Moana means “rainbow ocean” in Māori. The 12-year-old who won the contest to name the ship got an iPad Pro and a NZ $2,000 check for her school. The girl, who attends Rarotonga’s Seventh-day Adventist school, wrote in her submission that the name signifies God’s promise to never destroy the world again.

This article was developed with the support of Journalismfund Europe, and with reporting by Raf Custers and Greet Brauwers.

This article first appeared in Hakai Magazine and is republished here with permission.