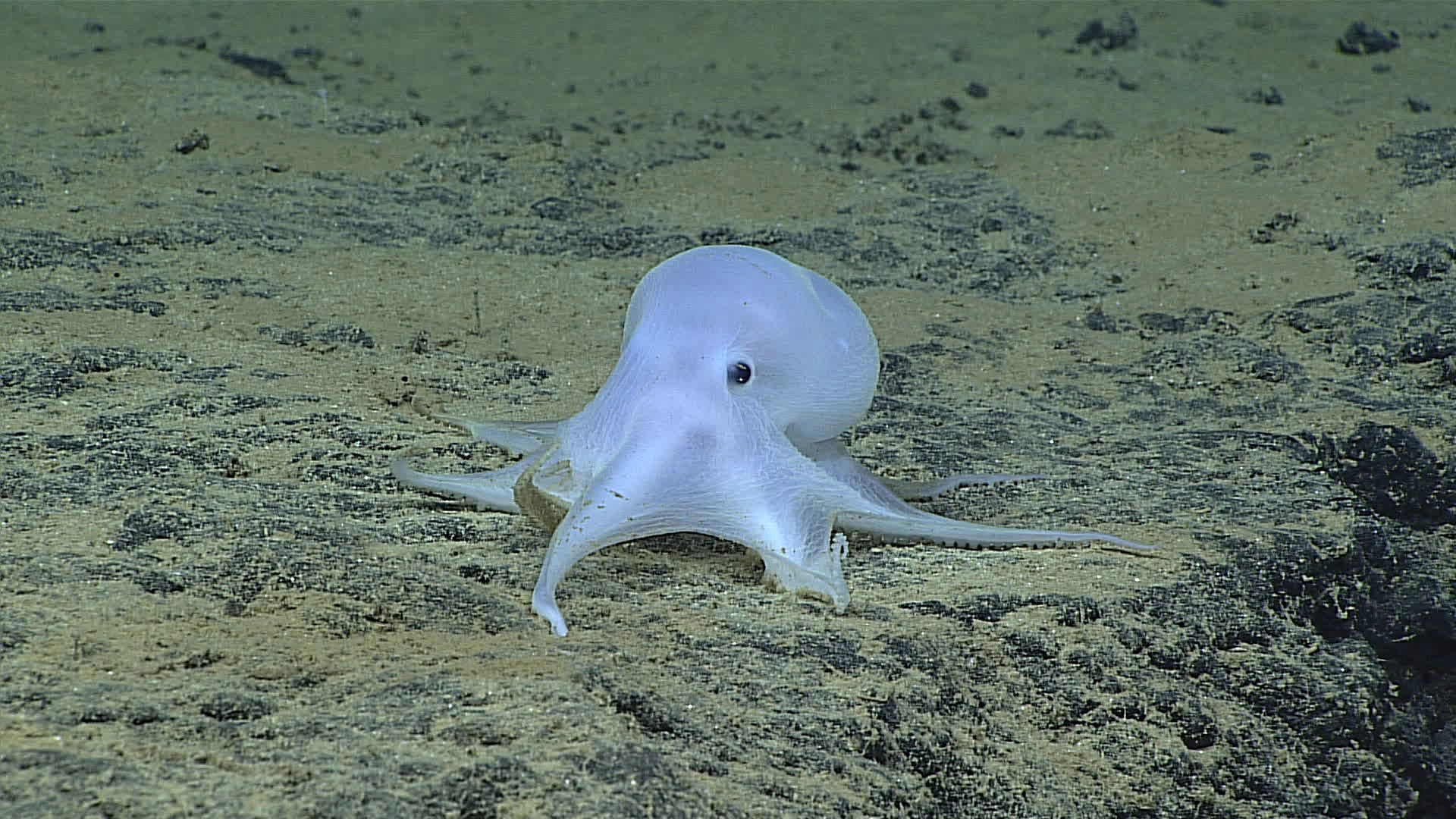

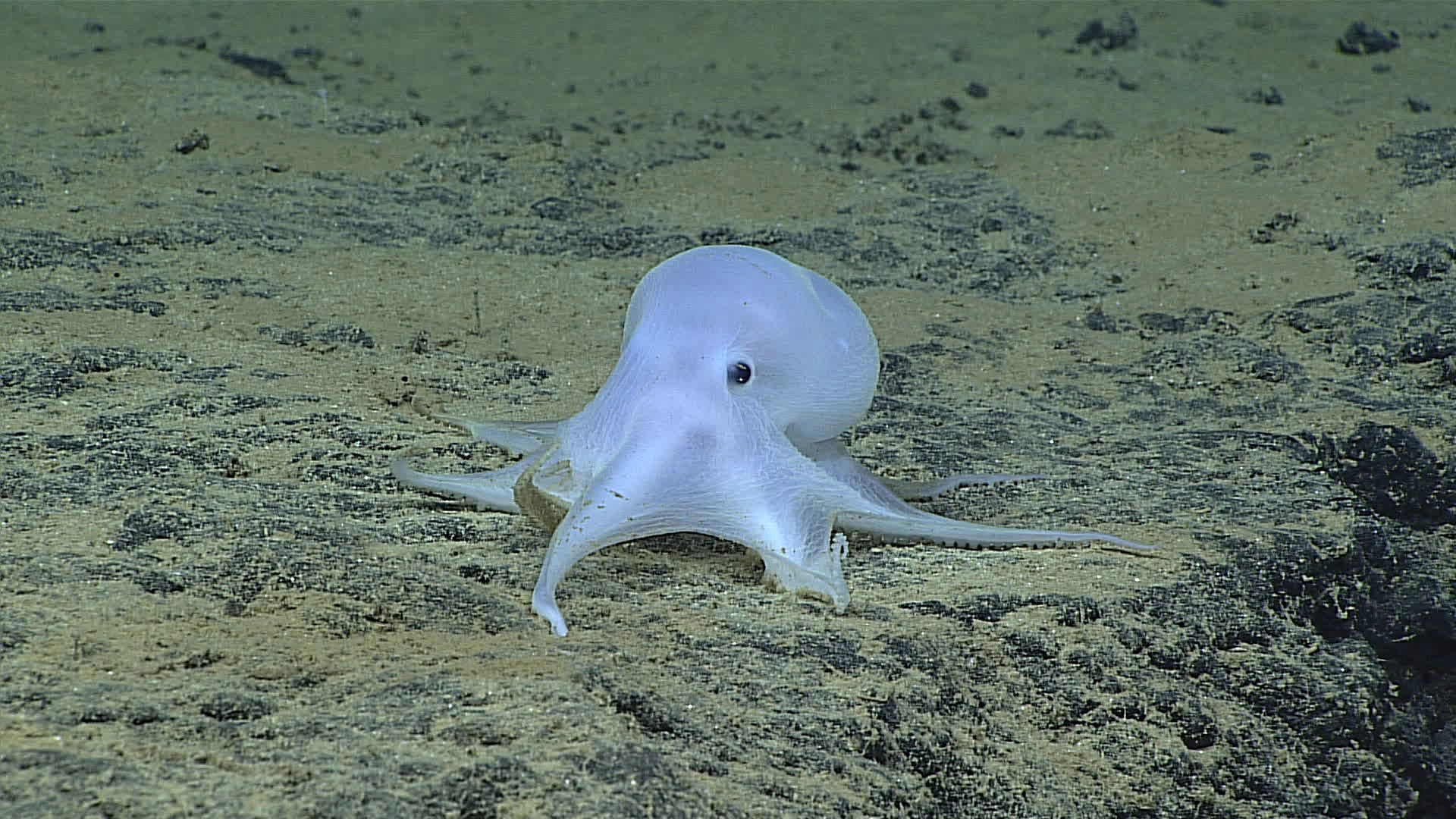

Remember the “Casper” octopod? Scientists spotted it on the ocean floor last spring. The pale little critter was seen chilling on the seafloor near Hawaii’s Necker Island, and researchers knew right away that it was almost certainly a species hitherto unknown to science.

Bad news, folks: According to a study published Monday in Current Biology, this creature—so recently discovered that scientists haven’t even figured out what octopus or cuttlefish it might be most closely related to—could be in peril. It lays its eggs atop minerals made precious by consumer tech goods.

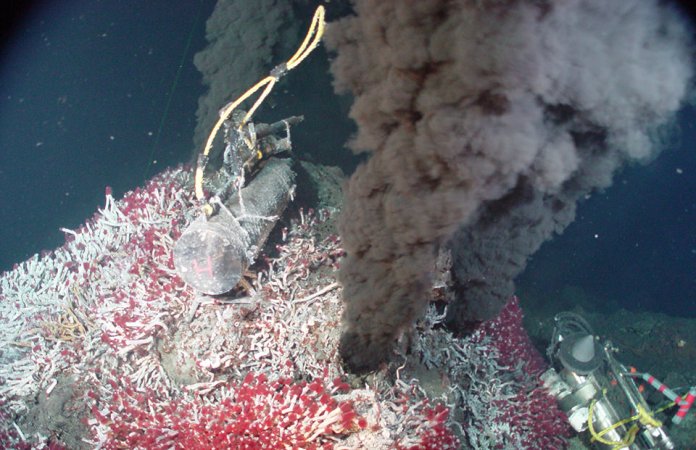

According to the latest research, “Casper” octopods lay their eggs at record-breaking depths: 4,000 meters below the surface or more. But unfortunately, they appear to lay their eggs only on one particular type of sponge that grows on top of manganese deposits.

“At a depth of 4000 meters, these animals had deposited their eggs onto the stems of dead sponges, which in turn had grown on manganese nodules,” lead study author Autun Purser of the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI) said in a statement. “The nodules served as the only anchoring point for the sponges on the otherwise very muddy seafloor. This means that without the manganese nodules the sponges would not have been able to live in this spot, and without sponges the octopuses would not have found a place to lay their eggs,” Purser explained.

Based on observations of nearly 30 of these animals, the researchers also believe that the octopods tend to hang out near the manganese nodules in general—even when they’re not breeding—perhaps because their main source of food is somehow associated with the deposits.

Unfortunately, Purser said, “many of the metals contained [in manganese nodules] are ‘high-tech’ metals, useful in producing mobile phones and other modern computing equipment, and most of the land sources of these metals have already been found and are becoming more expensive to buy.”

The nodules grow slowly, developing layer-by-layer like a pearl inside of an oyster. So if humans disturbed them, the octopods’ reproductive cycle could be disrupted for years to come. The study authors note that after scientists razed similar nodules during a 1980s experiment, some local fauna had not recovered even 26 years later.

For now, there are enough of these metals available on land to keep companies from trawling up manganese nodules. But many countries are investigating methods they might use to tap into these untouched resources in the future. This new study is just one reminder of the many potential consequences of deep-sea mining endeavors: The ocean floor is a diverse and fragile ecosystem which humans know little about, and industrial pursuits have the potential to throw the whole thing out of whack.