On July 19, a dozen teams gathered in hackerspaces around the country to await the rules of a 72-hour build competition. Red Bull, the energy drink brand and sponsor, announced the challenge at shortly after 6 p.m. Pacific time: Construct a game of games. It must be physical, not virtual; weigh less than 2,000 pounds; and have a clear winner. Inside the Mill, an industrial-arts shop in Minneapolis, Nathan Knutson, leader of the 1.21 Jigawatts team, and the rest of his 23-member squad began whiteboarding ideas. It had been a blazing hot summer, and by 2:30 a.m. all they’d settled on was making something with water.

The following morning, Knutson and four others met again. The founder of the Mill, Brian Boyle, suggested, “What about a submarine?” Within two hours, they’d drawn up the basic plans for a walk-through submarine disaster simulation game. They envisioned a player standing inside an open-ended replica of a sub’s control room, where he would extinguish threats by turning different valves or levers. Any delays would trigger a hull breach, spraying the player with water piped in from a nearby sink.

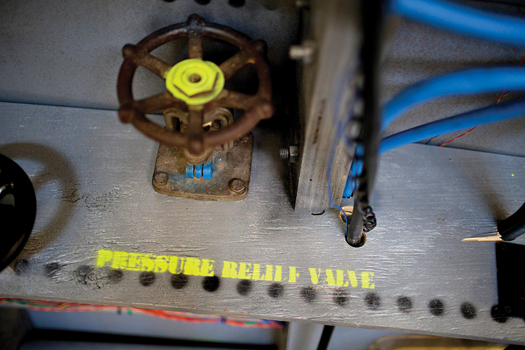

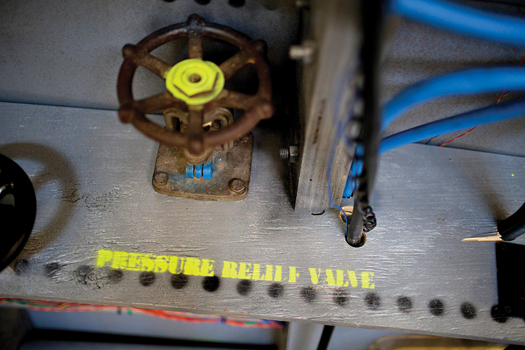

Knutson, an orthopedics implant engineer, drew up a rough list of materials. Then the team went shopping for electronically operated lawn sprinklers to douse the player, cast-iron valves to make the game look as nautical as possible, devices to rock the structure, plus sirens, buzzers, and red automotive tail lights for the emergency ambience. “We wanted it to tilt and move around and have sound effects,” Knutson says. “We wanted it to be an environment rather than something you looked at.”

The full team reconvened later that day and split up the tasks. One group used a CNC router to cut plywood into mock steel beams that would extend up and over the player’s head. Knutson wanted the wall, roof, and steel floor to shake, so he found an industrial DC motor to attach to the frame. When activated, it would cause the sub to rumble like an old car. Next, he hotwired an actuator that had once been used to lift and lower a hospital bed and affixed it to both the game’s frame and its base. Apivot sits between the two, so when the actuator extends or contracts, the whole sub tilts.

Brothers and electronics experts Tyler and Justin Cooper, meanwhile, began writing the software that governed gameplay. They programmed an Arduino to monitor Twitter for threats such as #firetorpedo. When enough people tweet the same threat, a warning sounds through the loudspeaker. If the player doesn’t react quickly enough, the Arduino opens the sprinkler valves and the sub shakes and sways.

Red Bull live-streamed each team’s build and asked viewers to vote for their favorite. Team 1.21 Jigawatts placed second behind a labyrinth game (right), but they hardly felt disappointed. “When you’re playing, it feels like you’re in the bulkhead of a sub,” Knutson says.

(See the details and two more projects on the next page)

BUILDING A SIM SUBMARINE

Time:72 hours

Cost: $2,500

TWO MORE GAMES

Dueling Labyrinths

Time: 72 hours

Cost: $1,000

Hack a Day website chief Caleb Kraft and his Springfield, Missouri, team built a pair of giant teetering tabletop mazes. In the game, two players per table compete to race a steel ball through their maze first. The wooden labyrinths proved easy to build, but mild panic set in as the 72-hour mark approached. The builders worked frantically to wire buttons and magnets so that competitors could temporarily trap their opponent’s steel ball. “We finished the electronics within the last half-hour,” Kraft says.

Thumb Wars

Time: 72 hours

Cost: $700

Twin brothers Pat and Mike Murray engaged in more than a few thumb wars as kids, so building a mechanized version of the classic game seemed like a no-brainer. As part of the Maker Twins, an eight-person team based in Scottsdale, Arizona, the duo built steel-and-plywood frames, covered them in foam, and wrapped the units in duct tape. When a player yanks a joystick, their faux thumb moves in the opposite direction. The first to pin an opponent for two seconds sets off a victory buzzer.

WARNING: We review all our projects before publishing them, but ultimately safety is your responsibility. Always wear protective gear, take proper safety precautions, and follow all laws and regulations.