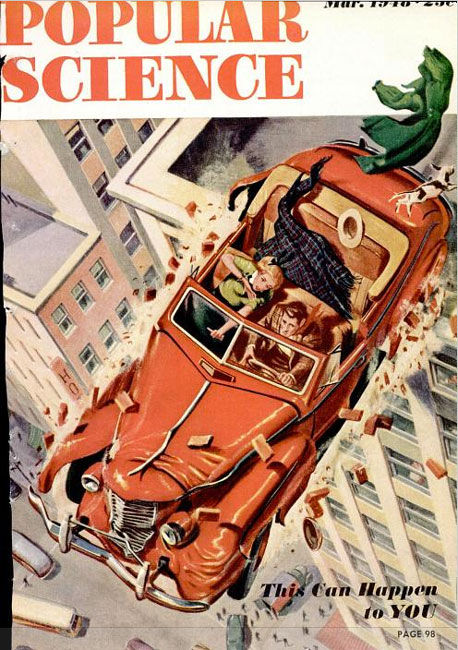

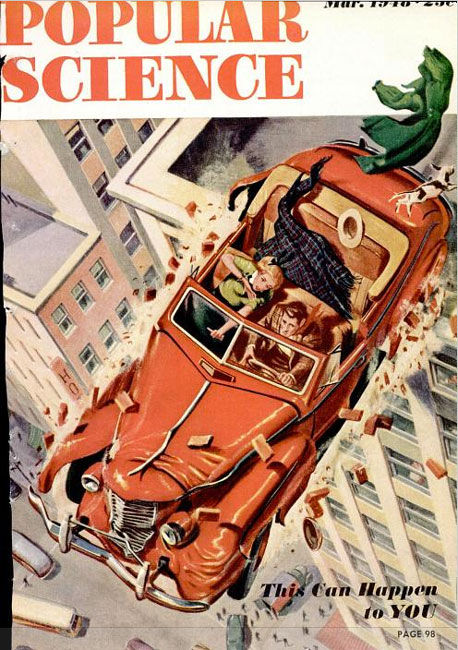

As terrifying as this cover is, we won’t lie, it’s a pretty accurate depiction of how we feel about our vehicles on a bad day. Car maintenance doesn’t come naturally to everyone, least of all first-time car owners in the 1920s. This week, we’re taking a look at some old school car safety and maintenance tips, mostly from the glory days of stick shift and all that entailed for rookie motorists.

People might have driven more slowly back then, but by the early 1930s, car accidents had become a national issue. During that era, we focused on some of the misconceptions behind automobile-related fatalities. For instance, most accidents took place during broad daylight, and in fine weather conditions, suggesting that drivers, not the machines, were to blame for all the casualties. Granted, we did occasionally see freak accidents between rogue stunt planes and parked cars, but for the most part, car owners were still figuring out how to navigate roads safely.

During the next decade, we published more practical articles on vehicle repairs and maintenance. Car ownership 101, if you will. How do you keep your tires from wearing out? What should you know about brakes? And what were the researchers in Detroit doing to make cars safer? Nowadays, it’s hard to remember that seat belts and windshield wipers weren’t always a standard feature in family vehicles, but during the mid-1940s, these safety innovations were worthy of six-page spreads. And why not? They saved lives, after all.

During the fall of 1922, we published a series on the hidden expenses of car maintenance. At the time, personal automobiles were a fairly novel luxury, which meant that plenty of new car owners were unaware of the “invisible demons of waste.” If readers understood how to take care of their cars, we argued, they could save half the costs wracked up by repairs at expensive garages.

The first article in this series dealt with engine troubles. What should you do when your car breaks down? While the process of flooding a carburetor or checking the circuits could sound intimidating, the answer was often more simple than you’d expect. Automobile expert Harold F. Blanchard recalled an incident where he helped a stalled motorist on a country road start his car again. After a few minutes of tinkering, Blanchard realized that the motorist’s vehicle had been filled with kerosene instead of gasoline.

“Detecting the cause of a dead engine is as interesting as taking part in a detective story, if you follow a systematic procedure and use your eyes and head as you go,” Blanchard said.

In 1932, we estimated that fatalities from automobile accidents increased by 24 percent in just a year. Between 1929 and 1931, the number of Americans killed by cars exceeded the number killed in the trenches during World War I. To help readers stay safe, we explored some of the different factors in accidents. In most cases, the drivers, not the machines, were at fault. The three most common causes of accidents were as follows: driving off the roadway, exceeding the speed limit, and driving ahead without having the right of way. Driving on the wrong side of the road, skidding, signaling improperly, and runaway vehicles without drivers also made roads a more dangerous place for pedestrians. Weekends also made for reckless driving, as 20 percent of all automobile fatalities occurred on a Sunday. The next most dangerous day to drive was Saturday, and after that, Thursday.

Despite its comical appeal, the illustration on the left depicts a real accident that occurred after an English stunt pilot smashed into a car while flying upside down. It wasn’t the car’s fault, of course, but as long as stunt flying was a trend, motorists were in danger of being ambushed by rogue aircraft. Luckily, the pilot involved in this incident escaped without harm.

To investigate new technologies in automobile safety, writer Devon Francis traveled to Detroit, where he asked designers how they built safer cars without compromising the vehicle’s aesthetics. Unfortunately, several of these well intentioned attempts at safety alienated customers. During the 1940s, engineers tried deepening the windshield of one model for the sake of visibility, but customers griped that they felt “exposed.” Other changes, such as tilt-beam headlights and windshield wipers, were more subtle, so customers didn’t mind them. Designers thinned out corner posts, installed leather-covered dashes, and made airplane-style seat belts a standard feature in automobiles.

If this cover image doesn’t terrify you into driving safely, we don’t know what will. According to the illustrator, driving 30 miles and hour is as dangerous as driving on the roof of a building. To keep readers from suffering such terrible fates, writers Devon Francis and John F. Stearns recommended memorizing the seven keys to safety, which are as follows: 1. Learn to judge the conditions of the road and the drivers. 2. It isn’t how fast you can go, it’s how fast you can stop. 3. Keep one car length between you and the car in front of you for every 10 miles on your speedometer. 4. Suspect every pedestrian of suicide. 5. Every intersection is a crash point, so slow down. 6. Signal properly. 7. Expect the worst from the other car.

According to the Association of Casualty and Surety companies, 40 percent of all mechanical defect accidents were caused by vehicles with defective breaks. So how were motorists supposed to maintain their breaks without spending loads of money on repairs? We recommended six simple tips: use breaks sparingly, pump the pedal frequently, build up the rate of deceleration while stopping from high speeds, stay off the brake pedal when trapped by a tight turn, use the break pedal to test for possible slipperiness during weather changes, and guard against growing accustomed to worn breaks.

In 1956, the Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory of Buffalo, NY, unveiled a car that could supposedly crash without killing any of its passengers. The inside of so-called Safety Vehicle bore little resemblance to its conventional counterparts. For one thing, the driver’s seat was located high in the center (to increase visibility), with one passenger facing the rear. Everybody sat in cozy bucket seats with individual seat belts. The front seat could slide back and forth. None of the seats could break free from the vehicle. To prevent passengers from hitting their heads, engineers placed the windshield farther in front of the driver and left a lot of space between the roof and the seats. Theoretically, the car could wrap itself around a telephone pole at 50 miles per hour without killing anybody inside of it. To ease driving, researchers replaced the steering wheel with levers that turn wheels hydraulically.

While the typical speed limits in the United States today run between 60 and 80 miles per hour, this wasn’t the case back in 1960, where you could be arrested for “speeding” at 32 m.p.h. on some highways. In what was considered a controversial article at the time, writer Paul Kearney argued that by overemphasizing speed limits, highway officials neglect more pressing problems, like drunk driving. Moreover, statistics showed that most of the recent accidents in Pennsylvania, Indiana, and New York involved vehicles driving slower than 50 miles per hour. More drivers died in New York after falling asleep at the wheel, hitting deer, or making various other “human errors.” Conversely, highways with moderately high speed limits experienced less accidents. Kearney noted that New Jersey drivers were safer overall because they weren’t so distracted by their fear of strict highway patrolmen, who had a reputation for cruising around in hope of busting people breaking the speed limit.

Nothing ruins a road trip like suffering a flat tire. To help readers keep their vacations problem-free, writer Robert Gorman asked engineers in Akron, OH for tips on maintaining one’s tires during a long trip. They recommended carrying your own gage and taking early morning tire readings each day, and repeat after an hour of driving. The rest is just common sense — before going on a long trip, raise our car on a lift and inspect the tires for cuts, bulges, and unevenness. Upgrade your rear tires by one size if you know you’ll be driving for a long time in hot weather.

Despite being intended for efficiency, highway signs can be hazardous when they’re ambiguously designed. During the late 1960s, Dr. Slade Hulbert, who worked in UCLA’s Institute of Transportation and Traffic Engineering, published pioneering research on the effectiveness of American highway signs. It was Hulbert who suggested using symbols on signs instead of words, as the latter are hard to make out while driving at 80 miles per hour. Not to mention that people who are illiterate or dyslexic will have trouble understanding sign semantics. Hulbert also found that arrows painted onto the pavement were more effective at directing highway traffic than the usual “do not enter” signs.