This isn’t a road in the sense that it has a name or can be found on a map. It’s just a trail covered with boulders and potholes superimposed on an inhospitable stretch of the Mojave Desert 25 miles south of Las Vegas. You wouldn’t dream of driving over it in a car. Even in a Jeep or a kick-ass 4×4, you’d crawl along in low gear, wincing at the toll it was taking on your tires, suspension and kidneys.

Alan Pflueger flies along it at 98 miles an hour. And that’s not “flying” used figuratively. He’s getting air under the tires of his two-and-a-half-ton truck as he vaults over crests and crashes into gullies with a giant plume of dust streaming in his wake. Pflueger’s flying machine is a purpose-built racing leviathan known as a Trophy-Truck. Created to conquer the Baja 1000, the world’s toughest off-road race, Trophy-Trucks cross the gnarliest terrain on the continent at speeds that can exceed 140 mph. Almost anything goes in this unlimited class, from 800-horsepower V8 engines to state-of-the-art electronics to titanium springs the size of laser-guided missiles. “Trophy-Trucks are the most complicated and sophisticated race vehicles in existence,” says former Nissan Motorsports chief Frank Honsowetz, who should know; his experience encompasses Baja, the Indy 500 and Le Mans.

Pflueger’s mount, in turn, is the most exotic, most advanced and, arguably, most ambitious Trophy-Truck ever built. In 2004 Pflueger hired celebrated racecar designer Trevor Harris to develop a vehicle that would use technology to tame the wilds of Baja. He was convinced that, with Harris as his secret weapon, he could follow the example of Formula One, where success is the product of perverse amounts of money and R&D. Two years and $1 million later, Pflueger is giving his baby its baptism of fire during a test session in the desert, a prelude to this month´s race. “The beauty of our sport is that there are hardly any rules to constrain you,” he says, “so I’m giving [Harris] the opportunity to be really creative. I could be wrong, but I´m betting that this is the Formula One car of off-road racing.”

Crazy From the Heat

The Baja 1000 is an epic orgy of speed, sleep deprivation and lunacy. Two-time winner Parnelli Jones once described it as “a 24-hour plane crash,” and that´s the easy part. Besides navigating treacherous terrain at an accident-waiting-to-happen pace, competitors also have to overcome logistical conundrums, wandering livestock, traps set by devious spectators, and the occasional drunk trying to drive the course backward.

The 1,000 miles of pavement, brush, rock trail, desert and dry lake between Tijuana and La Paz was first covered as a day-and-night-long expedition by a pair of intrepid American motorcyclists in 1962, and the first Mexican 1000 Rally was staged five years later. Sixty-eight vehicles started; only 31 finished, led by a dune buggy and a dirt bike. These days, the race is called the Tecate SCORE Baja 1000. And when the 39th annual event starts in Ensenada on November 16, Pflueger’s new truck should be among more than 300 entries in classes so diverse that even the competitors have trouble keeping them straight.

Racers don´t run Baja for the parsimonious prize money or limited television exposure. The vast majority of entrants compete strictly for fun. It´s hard on both the body and the pocketbook. But in the car-guy universe, no event scores more points for unadulterated machismo than the Baja 1000. Celebrities who have competed in it include prototypical stud Steve McQueen and borderline-certifiable rocker Ted Nugent. Its highest-profile champion, Ivan Stewart, is known as “Ironman.”

Pflueger, 39, fits the big-time Baja-racer profile: wealthy, adventurous and supercompetitive. He ran his first Baja–on a motorcycle–in 2000 and, like many before him, was immediately hooked. “Baja is the biggest playground you can imagine,” he says. “Where else can you go 1,000 miles with your foot to the floor and not see the same corner twice?” He quickly graduated to four wheels and, after some seasoning, moved up to Trophy-Trucks. These are the largest, fastest and most expensive vehicles on the scene. They´re built around tube-frame chassis clothed in bodywork based very loosely on everyday pickup trucks. The engines, generally huge American V8s, sit behind the driver to optimize weight distribution and improve traction. Their suspensions can absorb up to two feet worth of bumps at the front and three at the rear. Most run on 39-inch tires mounted on wheels that weigh upward of 140 pounds apiece. GPS navigation, live data acquisition and real-time telemetry are standard. “Driving them is the biggest adrenaline rush I’ve ever found,” Pflueger says.

A good used truck goes for about $250,000, and a top team might spend $750,000 on a potential race-winner. Money wasn’t an issue for Pflueger–he owns several car dealerships and real-estate developments in Hawaii–and he’s already invested in the Trophy-Truck he used to win the Baja 500 in 2004. But he wanted something better. And that meant looking outside the insular world of off-road racing.

Virtues of Independence

Trophy-Truck racing isn’t for the dilettante. Even for this low-key test south of Vegas, Pflueger Racing has shown up with a big rig, an RV-like fifth-wheel trailer, half a dozen pickup trucks, and a chase helicopter to shoot aerial footage of each run, not to mention two dozen engineers, mechanics and support personnel. “We’re here to try to break the new truck–literally,” Pflueger says. Which means the man on the hot seat is the truck’s designer, Trevor Harris, whose imprimatur can be found on virtually every component of the vehicle.

Harris is tall and lanky, with a slight limp that’s a legacy of childhood polio. At 68, despite Type 1 diabetes, which requires him to wear an insulin pump, he seems unaffected by the 100-plus-degree heat, and nothing fazes him. When team manager John Hoffman returns from the first test run complaining that the truck was so squirrelly it scared him to death, Harris remains imperturbably upbeat. “At least it’s still running!” he says with a wide smile.

Harris was among the first designers to apply formal engineering to road racing back in the early 1960s, and he´s been creating cutting-edge-and sometimes beyond-the-fringe-racecars ever since. His rsum includes stints in Formula One and Indy cars, and his prototype sports cars dominated the erstwhile Can-Am and GTP race series in the 1980s and early ’90s.

Yet nothing else is like Baja. “Running at ungodly speeds on such horrible terrain for 1,000 miles is an incredible challenge,” Harris says. Most Trophy-Trucks fight the course’s punishment with bulk–the trucks often weigh more than three tons and ride on suspension components stout enough to club an elephant to death. But this focus on durability has tended to blind off-road builders to technological developments in other forms of racing. Harris, free of such blinders, can apply his singular knowledge base to the restrictionless Trophy-Truck series in any way he sees fit. “In terms of rules, I have no restraints,” he says. “I find that liberating from a technical point of view.”

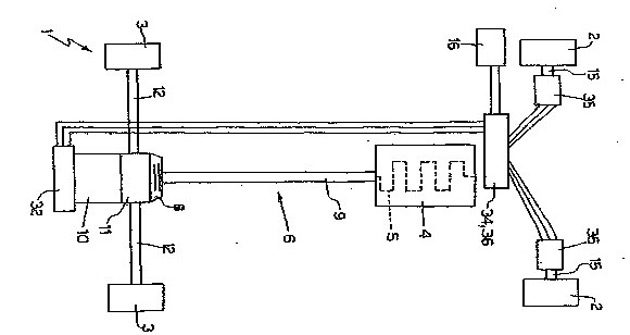

Most Trophy-Trucks run the same basic engine, so there’s no major advantage to be found there. (Pflueger Racing uses a 455-cubic-inch all-aluminum Chevy V8 massaged to produce 790 horsepower and 685 pound-feet of torque.) Instead Harris identified three areas where he could make a difference. First, he wanted his truck to be lighter than the competition. Second, he wanted it to handle better. Third, he wanted it to develop better traction. He realized that he could get elements of all three with a single piece of technology: an independent rear suspension.

Solid axles–the single bars that hold the wheels in place–have been around ever since prehistoric man figured out that two wheels were better than one. A few millennia later, automobile designers started attaching the front wheels to the chassis rather than to each other, thereby allowing them to move independently and maintain better contact with the road. But designing an independent rear suspension was complicated by the fact that the rear wheels also had to drive the car. (Trophy-Trucks eschew the weight penalties of four-wheel drive.) As a result, to this day, most of the trucks found on the street and in off-road racing use what’s known as a live axle–a solid axle that also directs power to the wheels.

Solid axles are cheap, simple and stout, and they’re great on flat, smooth roads. But they don’t work so well when the going gets rough because the wheels–yoked together by a single axle–can’t adjust independently to bumps, potholes and other variables. In off-road racing, where racers routinely encounter jumps, dips and obstacles that would prompt most motorists to speed-dial AAA, one wheel might be on the ground while the other is off. An independent rear suspension seems like the obvious solution, except that no one’s been able to make it work better than a live axle in off-road racing. “To put power down in the desert,” Harris says, “you’ve got to work out the numbers and geometry very carefully.”

Up until now, no Trophy-Truck with an independent rear suspension has been able to accommodate more than 22 inches of wheel travel. Going into this project, Harris decided that 30 inches was the minimum acceptable. To achieve this goal, he had to make the half-shafts–the components that route power from the differential to the wheels–as long as possible. This meant creating special wheels from scratch and designing a differential case that he calls “the most complicated drawing I’ve ever done.” Ninety hours of programming time were spent setting up the machine that would mill it out of aluminum billet. This was not inexpensive, but Pflueger made the investment. “Because I knew that if I didn’t build it,” he says with a smile, “somebody else would.”

Future Shocks

The hardest-working men at the test are a trio of Swedish engineers who are baby-sitting the brand-new shock absorbers, two per wheel, dubbed T Rex because they’re bigger and tougher than anything hlins Racing has ever developed. Although the unit had been tested comprehensively in the firm’s factory in Sweden, it isn’t performing as expected here in the Mojave Desert. To find out why, Johan Jarl, the lead engineer on the project, takes a ride with Pflueger. The experience leaves him dazed. Smiling wanly at Pflueger, he says, “His body must be made of different stuff than mine.”

To this point, Pflueger Racing had been using ultra-heavy-duty shocks built by small companies that specialize in this rarified arena. But Pflueger wanted to leverage the R&D resources and racing expertise of hlins, which makes shocks for Formula One, Indy, the Nextel Cup and the World Rally Championship. So in 2004 he flew Magnus Danek, the company’s chief automotive designer, to the U.S. and terrified him with a thrill ride around the Nevada desert to persuade him that off-road racing was the ultimate proving ground for shock absorbers. Danek left Nevada suitably convinced.

Shock absorbers don´t really absorb shock. They damp, or control, the energy of the springs. Typically, the damping force is provided by a piston drilled with small holes that telescopes up and down in a tube filled with gas-charged oil. As the piston cycles back and forth, it can create air bubbles that degrade shock performance. If the movement is especially violent, the hydraulic fluid can get so hot that the shocks burst into flames.

hlins has solved the heat problem in two ways: by carefully controlling the pressure of the oil in the shock and by adding little fins on the outside of the shock to dissipate heat. As the oil flows through the shock, a fiendishly complicated collection of teensy pieces called a shim stack controls the internal flow of hydraulic fluid. At the same time, hlins built a remote reservoir for the hydraulic fluid and sheathed the tubes connecting it in artistically finned aluminum extrusions. “Conventional off-road shocks have gotten bigger and bigger over the years, but they´re basically at the end of the road,” says Hoffman, the team´s resident shock expert. “By comparison, the hlins are rocket science.”

The real trial comes on the second day of testing, when the shocks are dialed in and integrated with Harris´s newfangled suspension. In back-to-back runs, the new truck is quicker and more predictable than the old one. “I don´t know if ‘boring’ is the right word,” Pflueger says, “but the new truck is so easy to drive that that’s almost what it is. With the old truck, I’m always busy working the steering wheel and the throttle. With the new truck, I just point it where I want to go and hit the gas pedal. It drives like you took it off the showroom floor. I could race it in Mexico right now.”

After hearing this upbeat assessment, I’m ready for a ride. As Hoffman takes off, the truck feels ponderous; it seems to brake, corner, and accelerate in slow motion. But as we pick up speed, I´m stunned by how plush the ride is. Don´t get me wrong: This is a racecar, not a limousine. But we´re careering over the worst terrain I´ve ever been on, and the truck seems to float over the bumps like a flying carpet. We slow to a crawl in the rough stuff–rocky up-and-down sections that would be perfect for hiking. Here Hoffman works the gas pedal more gingerly, accelerating up the inclines and breathing the throttle as we climb over the tops. I sense the wheels extending fully in bump and rebound (as the motion is called), and every now and then, there´s an ugly metallic crunch as the chassis slams into the ground.

It´s hard to believe that anything can survive this kind of pounding. Frankly, I´m amazed that the wheels don’t shear off, the suspension doesn’t collapse, and the body doesn’t crumple up like a paper bag in a trash compactor. And as it happens, the new truck is slowed by various problems the next day and stops working entirely the following morning. Clearly, there’s much to be done. But none of the issues are showstoppers, and the test convinces Pflueger that he owns the fastest Trophy-Truck in existence. “But I’d like this truck to be so dominant,” he says, “that it takes everybody two years to catch up with us.”

Update: The problems that surfaced during the test in the desert forced Harris to redesign several components. In late September (after we went to press with the November issue, in which this story ran), the team decided to focus its efforts on its older, but proven, Trophy-Truck and delay the new one’s debut until 2007.

In the June issue, Preston Lerner wrote about cars designed to stay on the road.