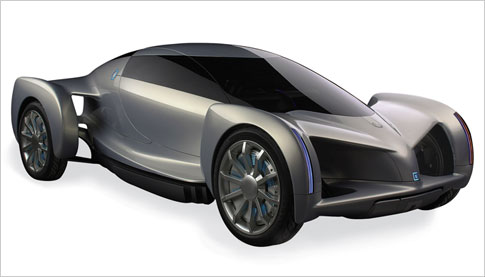

Burt Rutan, the visionary aircraft designer who created the first privately funded manned space vehicle, SpaceShipOne, told me a story recently about his EV1 electric car. He had happily driven the vehicle for years until General Motors decided not only to take it off the market but to take back all the leased vehicles that were on the road. “The day they came to get it, I was on the verge of hiding the thing in a cave,” he recalled. “I was going to show them an obliterated, burned-up airplane carcass and say, ‘There it is-go ahead and take it!'”

Instead, he sadly watched them haul away his EV1 on a flatbed truck. He was one of hundreds of owners of the sporty, fast, nonpolluting cars that GM reclaimed in 2003 and 2004 because, the company said, there was “no market” for them. “There are still times that I drive home, pull into the garage, and reach for the cable to plug in my car before I remember it’s long gone,” Rutan said.

Chris Paine’s documentary film Who Killed the Electric Car? argues convincingly that there was indeed a market for the cars-and a devoted one, at that-but that GM squashed the EV1 because, quite simply, it threatened the livelihood of the entire automotive industry. The car used no gasoline, no oil and no mufflers, and it required only sporadic brake maintenance. Each of these components represents billions of dollars in profits for the industry. GM, the oil companies and various government agencies argued that the car wasn’t practical, didn’t have enough range for consumers and was less promising than the apparently imminent hydrogen technology. The reality was exactly the opposite, Paine’s film suggests-the viability of hydrogen as an automotive fuel source alone is in fact almost comically optimistic.

The whisper-quiet EV1 was designed by another aviation pioneer, Paul MacCready of AeroVironment. In the 1970s, MacCready built the only successful human-powered aircraft, the Gossamer Condor and the Gossamer Albatross. His solar-powered electric car Sunraycer, built for GM, won the 1987 World Solar Challenge Race in Australia. His corporate mantra is “do more with less”-that is, focus on creating vehicles that require less energy to operate, not on finding ways to pump more power into inefficient systems. His team’s battery-powered EV1 was a triumph of engineering and a joy to operate.

Who Killed the Electric Car? begins with a mock funeral that was held in Los Angeles in July 2003, before the final EV1s were collected. Paine methodically presents his case with an onslaught of damning statistics about fossil-fuel consumption and a parade of EV1 enthusiasts, including actors Mel Gibson and Peter Horton, comic Phyllis Diller-who recalls the early electric vehicles from before the 1920s-and many notable automotive and energy experts. Two heroes emerge in Chelsea Sexton, an EV1 sales specialist whose emotional attachment to the car is palpable, and cowboy-hatted S. David Freeman, an influential former energy adviser to President Jimmy Carter who speaks in a slow Texas drawl of the broad conspiracies that sealed the EV1’s fate.

Those conspiracies are complicated and far-reaching but are essentially based in the California Air Resources Board’s inability to stand up to pressure from corporate and government entities that wanted it to rescind its 10 percent mandate for zero-emission vehicles. It was that mandate that had spurred GM to create the EV1 and introduce it in California. When the company realized the bottom-line implications of the car, it reduced its marketing program for it to a series of cryptic, uninspiring print ads and watched as public awareness unsurprisingly dwindled. GM, along with DaimlerChrysler and the U.S. Department of Justice, then sued CARB to rescind its mandate. The board eventually watered it down under new leadership-chairman Alan Lloyd, who has been heavily involved in the promotion of hydrogen-fuel-cell technology-to the point that electric vehicles were no longer a required part of manufacturer fleets, thus consigning the EV1 to the dustbins of automotive history.

The film ends with a poignant observation of the fate of the cars-all but a few museum pieces were crushed in the Arizona desert-and a “guilty/not guilty” sequence of the suspects in its mock murder trial. (There’s only one “not guilty”, and it’s something of a surprise.) But the urgent question in the aftermath is whether the electric car, given proper support, could be a viable alternative to fossil-fuel-burning automobiles. After watching Who Killed the Electric Car?, with its exciting depictions of the EV1 racing down the streets while leaving no pollution in its wake, the answer, frustratingly, seems to be yes.