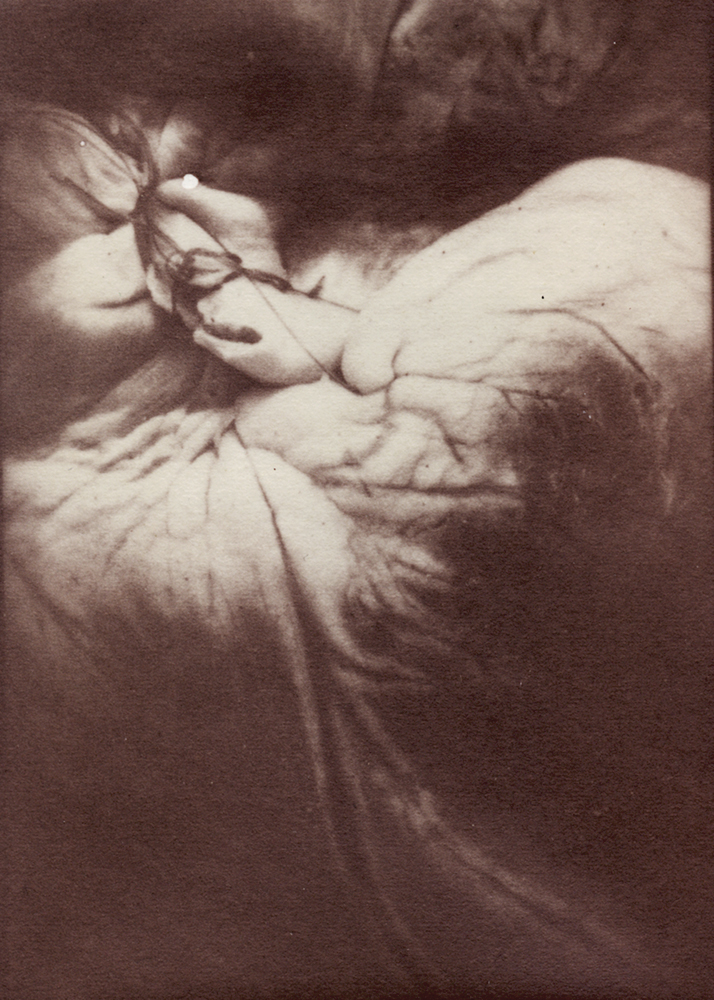

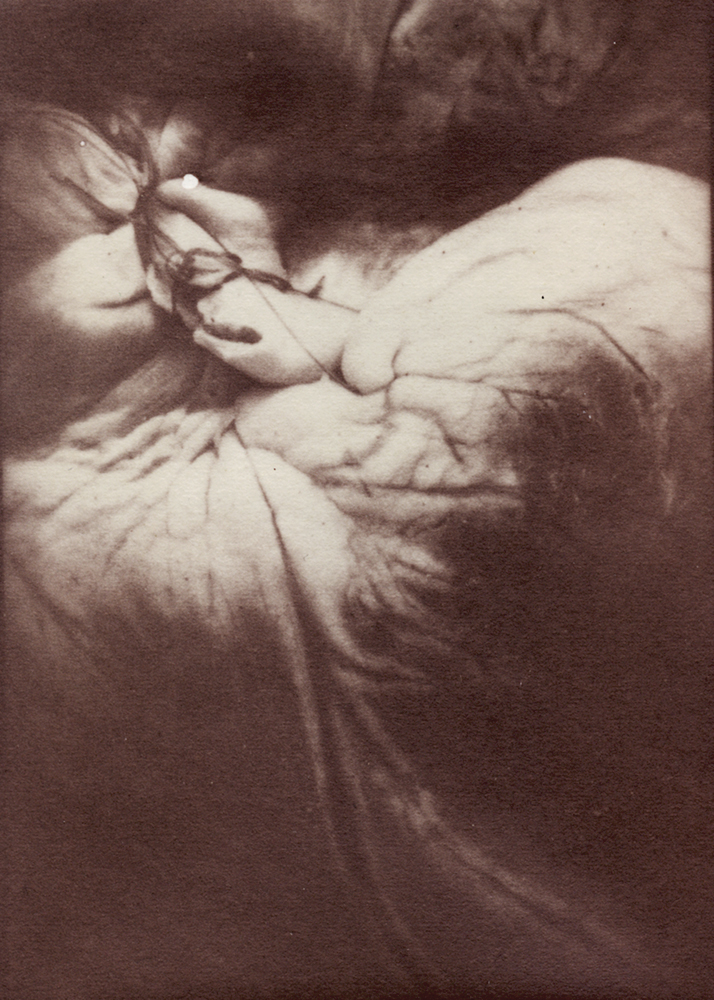

This spring, as biologist-turned-artist Jaden Hastings was developing her new prints, she noticed something strange. The maroon-colored images smelled faintly of blood—particularly her own blood. The sharp scent was an intimate reminder that the prints came, at least partly, from her body.

Hastings is a bioartist who uses living tissues and organisms as her medium. To make the prints, which she calls “plasmatypes” after the plasma in blood, she drained half a pint of her own blood. Periodically, over the course of months at her studio, Hastings wrapped a tourniquet around her arm, drove a needle into her veins, and pumped out five vials at a time. She then mixed the blood serum with other chemicals to produce a homemade light-sensitive fluid she could slather on paper. “I am not the least bit squeamish when it comes to blood or needles,” Hastings says.

Hastings discovered the technique last winter when she stumbled across an article about one of the first photographic printing processes called albumen printing. Invented in 1850 by French photographer Louis Désiré Blanquart-Evrard, the technique uses a protein in egg whites called albumin as a binding agent for photographic chemicals. Paper coated in egg whites, salt, and silver nitrate became the world’s first commercial photo paper.

The article also mentioned that albumin is found in blood. The protein transports nutrients and keeps fluid from leaking out of vessels. Hastings started to rethink the process of printmaking. “I love a good protocol that I can play with and make my own,” she says.

With her plasmatypes, Hastings joins a long line of artists using blood in their work. In the 1960s and 1970s, artists Hermann Nitsch and Judy Chicago used animal and menstrual blood in performances and art installations. Blood amped up the emotional response to the artists’ explorations of martyrdom, penance, and womanhood.

Artists still use blood as a powerful symbol. For example, Jordan Eagles’ Blood Mirror is a seven-foot Plexiglas slab containing the blood of nine gay, bisexual, and transgender men and a protest against the laws restricting gay men from being blood donors. The piece is currently on exhibit at Trinity Church in New York City.

A growing number of today’s artists, however, use blood less symbolically and more clinically “as a technology and raw material for manipulation,” says Ionat Zurr, an artist who helped pioneer bioart in the mid-1990s. Treating blood as a mode of production prompts audiences to experience the utility of biology alongside its cultural significance. “Eventually everyone has the realization, ‘Oh wow, that was made using the artist’s blood,'” Zurr says.

This spring, Hastings tested her plasmatypes at SymbioticA, a bioart laboratory at the University of Western Australia. She printed a series she calls Primitiae, which features magnified images of meteorite interiors taken under a microscope. Hastings says that her blood is a reminder that the matter in our bodies may have come from meteorites from billions of years ago.