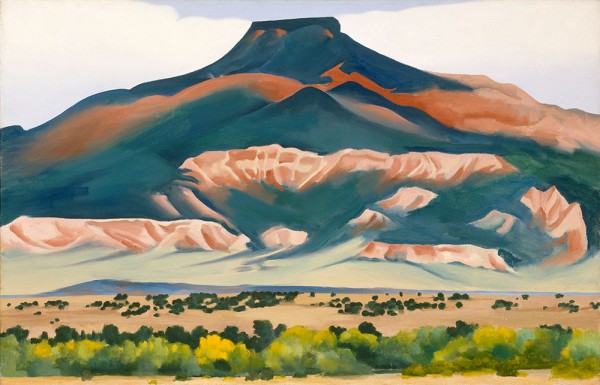

Georgia O’Keeffe is famous for her flowers—erotic red canna lilies, hypnotic Jimson weed, blooming calla lilies. But a more sacred subject may have been the Pedernal mesa, an iconic peak in the flat New Mexico landscape.

“It’s my private mountain. It belongs to me,” O’Keeffe said of the Pedernal, which she painted from her studio on the red earthed Ghost Ranch. “God told me if I painted it enough, I could have it.”

Unfortunately, God (or, in this case, metal soaps) also taketh away.

O’Keeffe’s “Pedernal, 1941”—a sweeping vista of pinks, greens, and yellows creeping up the canvas to the mountain’s darkened summit—is experiencing a peculiar kind of decay. The artist noticed it herself, remarking on granulations, discoloration, and small spots where the paint disappeared altogether in letters to conservator Caroline Keck in 1947. Known as surface protrusions, or “art acne”, this pimpling afflicts oil paintings from every time and place. But the reasons for O’Keeffe’s deformations, which only grew worse over the decades, remained a mystery.

In a feat of artistic sleuthing researchers at Northwestern University finally identified the origin of these “caldera-like” deformations in O’Keeffe’s paintings. Their results will be published in the forthcoming academic text Metal Soaps in Art. In the process, the researchers also devised a new handheld tool for curators to investigate pimples in their own collections. The technology was demonstrated at the 2019 American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) conference in Washington, D.C. on Saturday.

It began with a plea to Marc Walton, a material scientist and co-director of the Center for Scientific Studies in the Arts. A collaboration between Northwestern University and the Art Institute of Chicago, the center’s mission is to help small-scale museums with big-time artifacts preserve their collections. “This is how our lab often works,” Walton says. “We’ll get some strange request from a cultural heritage institution—it’s often an object that has a problem—and we’ll respond to it.” In this case, Dale Kronkright of the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe reached out about protrusions on many of the artist’s canvases between 1920 and 1950, including the 1941 rendering of Pedernal.

At first, it seemed like a straightforward chemistry project. Simply analyze the materials in the paint, the condition of the canvas, and the environment in which the works are stored for clues, and report back on what might be making these pigments pop. But, Walton said, it quickly became an opportunity for a new kind of technological experiment, with Pedernal as the first subject.

“We had a lot of tools in our toolkit to answer that question [of protrusion formation], but they were bulky, they were difficult to transport and set up, so we rethought the problem and decided we could do better,” he says. Working with Ollie Cossairt, an expert in computational imaging at Northwestern’s Comp Photo Lab, they built a 3-D imaging technique that requires only a smartphone or tablet to analyze diverse surfaces.

It works like this: Curators can open a predetermined pattern on their LCD display, beam it at the painting, and take a picture with the front-facing camera. They then upload that information to the cloud, where it’s fed through an image-processing algorithm, which returns highly-detailed, localized images of the artwork’s surface. “By analyzing the way those patterns are distorted, you can actually determine the shape that’s reflecting,” Cossairt says. Right now, curators must identify individual protrusions manually, but Cossairt says the next phase of research will seek to automate that process as well.

When they turned their clever new gadget on O’Keeffe’s painting of Pedernal, the researchers found the protrusions clustered on light-colored paints and were almost entirely absent from darker areas. It didn’t have anything to do with the base pigment itself—the light green and dark green were both derived from cadmium, in this case a benign element. Rather, the problem arose when O’Keeffe added lead white to lighten each shade, triggering the inflammation.

As Kassia St. Clair writes in her book, The Secret Lives of Color, lead white has been manufactured since at least 2300 B.C.E. and its production has changed very little since Pliny the Elder shared his methods in the first century C.E. Lead was first extracted from rocks, then placed into one side of a two-holed clay pot. In the other vestibule went vinegar. And the receptacles were surrounded by poop. “Fumes from the vinegar reacted with the lead to form lead acetate; as the dung fermented it let off CO2, which, in turn, reacted with the acetate, turning it into carbonate,” St. Clair writes. “After a month some poor soul was sent into the stench to fetch the pieces of lead, by now covered in a puff-pastry-like layer of white lead carbonate, which was ready to be powdered, formed into patties, and sold.” The process was dangerous, as was the pigment itself if ingested. But artists liked lead white’s durability and price point, so it remained on artist’s palettes well into the 20th century.

Art acne first received wide recognition at the turn of the millennium, after conservator Petria Noble identified pimpling on Rembrandt’s “Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp” in 1996. An investigation concluded that the 16th century Dutch master’s oil painting was plagued by lead soap. Since then, chemist Joen Hermans told *Chemical & Engineering News”, anxious conservators around the world have been “literally watching paint dry.”

With the new tools described in Walton and Cossairt’s research, this vigil will be even more precise. According to Walton, the demo at AAAS will prove “it’s possible on a mobile device… to get these millimeter-level measurement.” But, he adds, “we’re 5 or 6 years away from something as good as a standard interferometer,” the expensive, intensive, and oversized tool currently in use.

For now, the team is testing their technology on some other iconic works. In addition to paintings in the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum’s collection, Walton and Cossairt have a forthcoming study on the same mobile imaging device and its success with stained glass artwork, like the Art Nouveau windows Louis Comfort Tiffany manufactured with Kokomo Opalescent Glass. If all goes well, Cossairt says, one day every curator, auctioneer, and art enthusiast will have a Star Trek-style tool for instantaneous artwork evaluation at their fingertips.