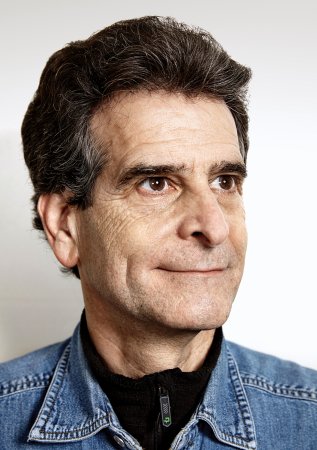

By day Arden Warner is a physicist at the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, working on the next generation of particle accelerators. After hours, he has been devising a non-toxic way to clean up oil spills.

It began in 2010. Warner and his wife were troubled by what they were hearing and seeing in the news about the BP oil disaster in the Gulf of Mexico. Like many others around the country at the time, they wondered if the clean-up process could be improved technologically.

“My wife asked me, what would I try to do?” says Warner. “In my naïve way of thinking about things, I thought, ‘there are four forces we know about, and only one I really know about: electromagnetic force.’” But how could he magnetize oil?

Later in the evening it came to him. “When you put magnetizable material in a solution, it’s randomly caught up in the solution,” Warner explains. “Apply a magnetic field, and the particles will line up in the direction of the field. Orthogonally to that direction, the fluid becomes more rigid, and you can move or manipulate, it.”

That night Warner went to his garage. He shaved some iron off a shovel and mixed those filings into a bit of engine oil. Then he applied a small magnet to the solution and tried to move it – and it worked. This was proof enough of concept to fuel “countless hours” of experimentation. “When I started on it, I couldn’t sleep for days,” he says, but would instead come home from an eight-hour work day to spend another 12 on devising an effective “pseudo-magnetorheostatic” fluid. “I spent, I’d say, almost every evening testing a different oil, a different way of doing it.”

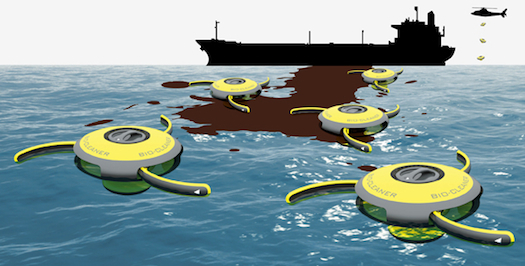

Warner settled on using magnetite dust of about two to six microns in diameter, and tested it in over 100 oils. Crude oils turned out to have enough inherent viscosity – meaning a natural tendency to resist flowing – that they lent themselves pretty well to being magnetized and then cleared away with magnetic force. “You can size the particles to the depth you need to go,” Warner says, and “they will descend in the water and mix with the oil very well, and form a very nice bond. You can pull oil up from the bottom.” Then it’s a matter of finding mechanical ways to gather up the oil – perhaps using booms with an electromagnetic charge – and remove it.

The magnetite particles themselves could be cleaned and re-used, he theorizes.

Warner envisions additional ways to apply the process, from cleaning up everyday small spills in garages to saving oil-soaked wildlife and natural environments. “A swamp is no different from water with lots of vegetation in it,” says Warner. “This stuff grabs onto the oil rather strongly, and doesn’t grab onto the water, and grabs onto oil on other surfaces as well, and you can literally pull it out.” Warner has oiled bird feathers, then added magnetite and applied magnetic force to remove the oil. “It was very effective,” he says.

Fermilab helped Warner patent the process, but developing it further is beyond the lab’s mission of accelerator physics. Thanks to coverage of his process in a recent lab newsletter, however, Warner says he has gotten email from several outside parties, including some plausible commercial development partners.

“I think that the environmentally friendly nature of this thing is worth, alone, makes it worth pursuing,” says Warner. “Adding magnetite to water seems more natural than adding chemicals” to clean up oil.

“I’m originally from the Caribbean, from Barbados, where the ocean is a part of me,” Warner says, “Coming from an island – it does motivate you.”