This story originally featured on Field & Stream.

The battle over Pebble Mine—and the fate of the world’s largest salmon run—is expected to hit a major turning point this month. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ final Environmental Impact Statement, a key document in permitting the controversial mine, may arrive as early as June 15. That document will ultimately present the argument for approving or denying the project’s required Clean Water Act 404 permit, and effectively kill the mine plan or bolster its growing momentum. A final determination on the permit is expected later this year.

“Things are getting serious,” says Nelli Williams, Alaska Director for Trout Unlimited. “The massive impacts of this project are now clear. The review process has proven inadequate at best. The permit should not be issued, but only time will tell, and that time is coming quickly.”

Why the Pebble Mine is dangerous

The proposed Pebble Mine would sit atop the largest-known undeveloped deposit of copper and gold in the world—a mother lode that could be worth some $40 billion over the project’s 20-year first phase, and potentially hundreds of billions over a full-scale 78-year development. Yet that same ground filters rainfall and snowmelt that feeds an expansive network of rivers and small streams that make up the watershed of Bristol Bay in southwest Alaska.

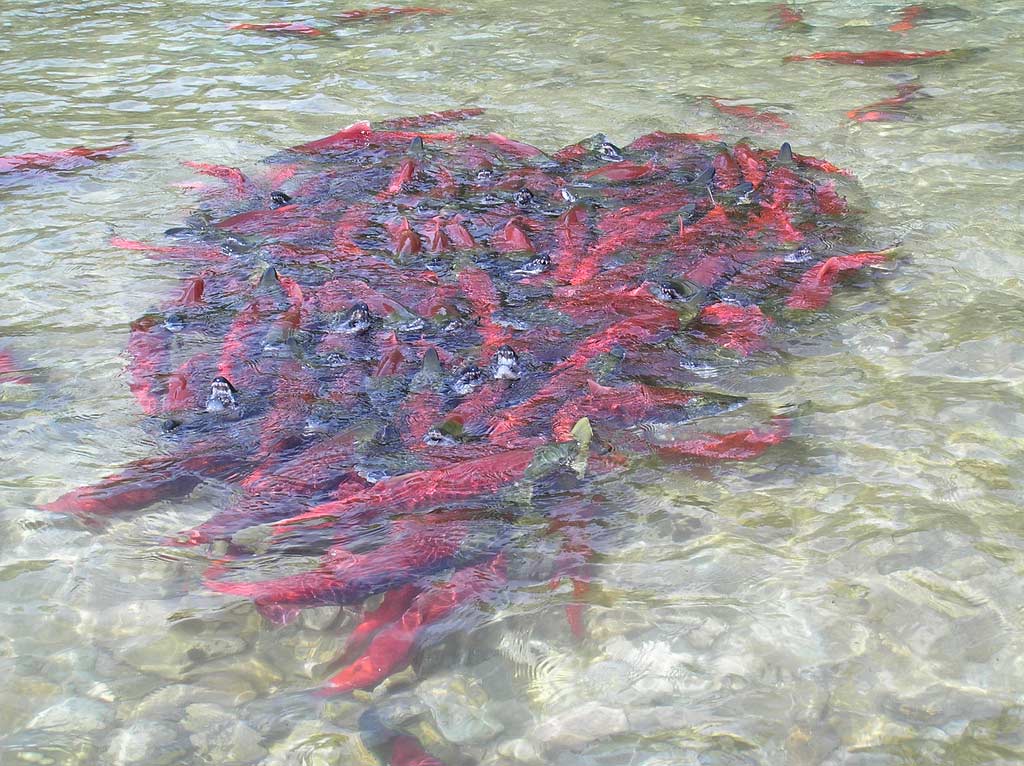

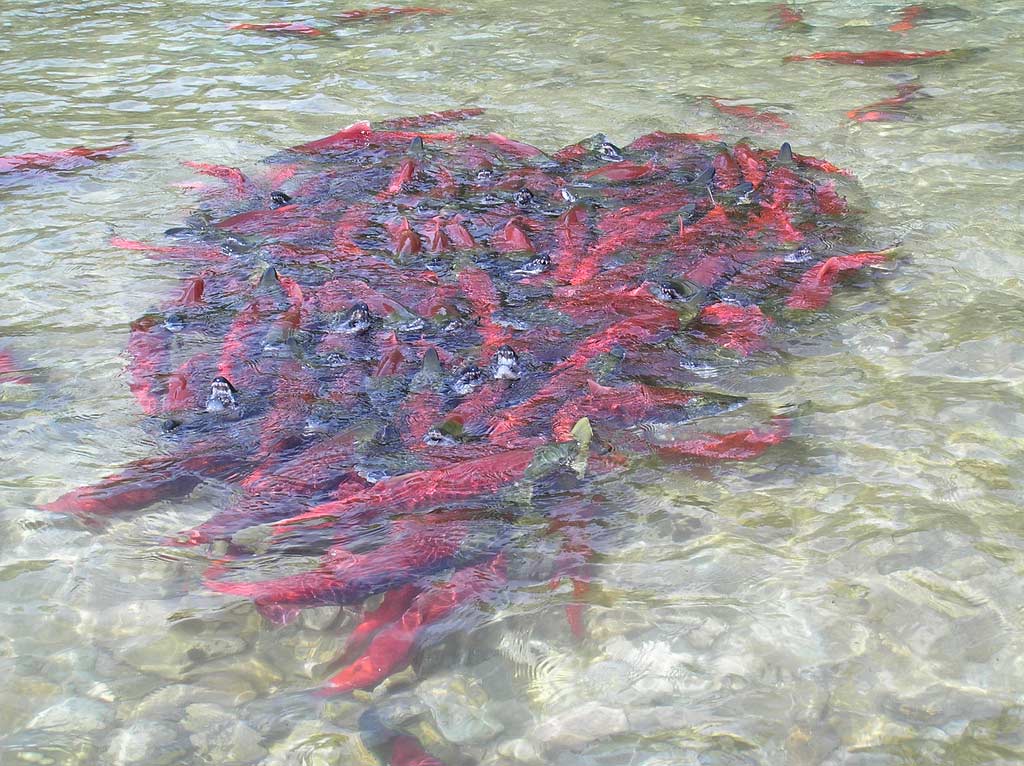

All five Pacific salmon species spawn in the bay’s freshwater tributaries. Many fear that mining that earth—along with the expansive footprint of roads, ports, and the industrial traffic it would bring to the region—would be a death sentence for the planet’s last best salmon fishery.

When I toured the mine site in 2018, I was immediately struck by all the water. From the helicopter, the rolling lowland bluffs of southwest Alaska look rocky and hard-packed. But with my first step off the chopper by Frying Pan Lake, I sank to my ankles in swamp. The ground at the mine site and surrounding it is like a giant sponge that holds, filters, and trickles water into the expansive Bristol Bay ecosystem.

Pebble Mine would not be a classic hard-rock mine, where miners use pickaxes and shovels to produce handfuls of precious metal. The valuable rare-earth minerals under Pebble are thin and spread like a few grains of salt in a bucket of sand. Mining that ground would require pumping and filtering the soft earth to capture flecks of high-dollar minerals. The giant hole they are proposing—as deep as the Empire State Building is tall—would constantly fill with water, which would have to be pumped, processed, filtered, and cleaned, before returning to the environment.

According to a draft of the Environmental Impact Statement, the current mine plan would destroy 105.4 miles of streams and 2,226 acres of wetland. The longer-term 78-year plan, which Pebble owners Northern Dynasty Minerals Ltd. is pitching to investors, would chew up 300 miles of stream and 10,000 acres of wetland.

What people are doing about it

More than 250 national outdoor sporting businesses and organizations, representing millions of hunters, anglers, and outdoor enthusiasts, sent a letter to the Trump Administration in May urging the Corps to deny the permit for these reasons and more. “The review process continues to rely on an incomplete and changing permit application and mine plan,” they wrote.

Many other opponents of the mine take this line of argument, pointing to what Sen. Lisa Murkowski called the “data gaps” in the current mining plan.

In a draft of the environmental report expected on June 15, the Environmental Protection Agency told the Corps that Pebble Mine, “may have substantial and unacceptable adverse impacts on fisheries resources in the project area watersheds, which are aquatic resources of national importance.” The EPA sent a letter late last week emphasizing their concerns, adding that “such information should be reflected in the Corps permit record.”

Documents obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request by Bristol Bay Native Corporation brought to light concerns from the EPA, and a laundry list of other agencies about the project plan:

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: “It appears that no compensation is being provided for the permanent loss of more than 2,000 acres of wetlands in the Nushagak River watershed and that no compensation is being provided for more than 90 miles of permanent stream loss …”

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service: “[The mine] would erode the portfolio of habitat diversity and associated life history diversity that stabilize annual salmon returns to the Bristol Bay region.”

- Alaska Department of Natural Resources: “[The mine waste storage plan] does not appear to be reasonable, practicable, or safe.”

- AECOM, the engineering firm contracted to vet the mine design, pointed out that the dam constructed to hold back mining waste in perpetuity, “could slide into potentially undrained tailings and have consequent effects in a downstream direction.” In layman’s terms, the acidic mine waste could leak downstream and into the greater Bristol Bay ecosystem.

The Army Corps keeps changing the plan

Through this all, the mine plan keeps changing. Northern Dynasty Minerals and Pebble Partnership have caught flack in the press for these last-minute changes, but in fact, the cause of confusion rests squarely on the Army Corps, which continues to oscillate on what version of the development plan will cause the least amount of environmental impact.

For example, if the Pebble Mine is developed, one of the significant impacts won’t just be the giant hole in the ground, but an expansive transportation network required to connect the mine site to the rest of the world. When I toured the area two years ago, the best plan involved an ice-breaking ferry crossing Lake Iliamna and a relatively short road system connecting the ferry port to a shipping terminal on Cook Inlet.

As of May, that changed when the Corps of Engineers said their preferred route now is an 84-mile northern overland road from a port on Diamond Point. That itself is highly problematic, because the landowners on Diamond Point have said they’re not interested in working with Pebble. The Igiugig Village Council owns the land at Diamond Point where the new Corps’ preferred route calls for a shipping port. The council issued a statement on Monday saying they “should not be considered an acceptable alternative.” Village leaders Christina and Alexanna Salmon are longtime vocal critics of the mine.

What you can do to stop the Pebble Mine

“At this point, there’s a huge stack of evidence that this permit should not be issued,” Williams with Trout Unlimited says. “But these decisions are made partly on science and partly on politics, and the hunting and angling community carry a lot of weight.”

If you want to help make a difference, call your Congressional representatives and tell them how you feel about Pebble Mine and Bristol Bay. Visit savebristolbay.org or defendbristolbay.org to write elected officials and to stay abreast of the news.

“If we can hold them off a little longer,” Williams says, “we can change the conversation to supporting local communities and keeping the excellent fishery and habitat we love alive and healthy—the way it is now, and the way it should be forever.”