When Yuri Milner sends hundreds of spaceships to Alpha Centuri to hunt for alien life, they might look a lot like something we’ve seen before.

In a meeting with Popular Science before the announcement, the Russian billionaire produced an example of the technology he’s considering as the basis for the interstellar mission: an extremely small satellite weighing just 1-2 grams, originally funded on Kickstarter.

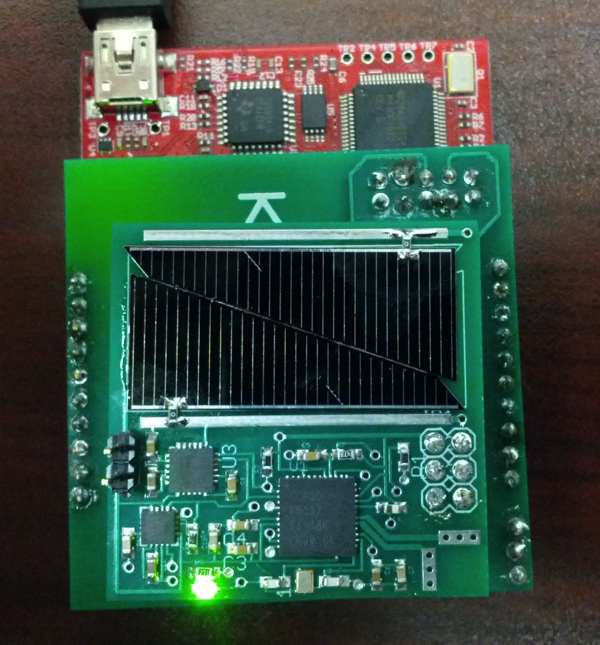

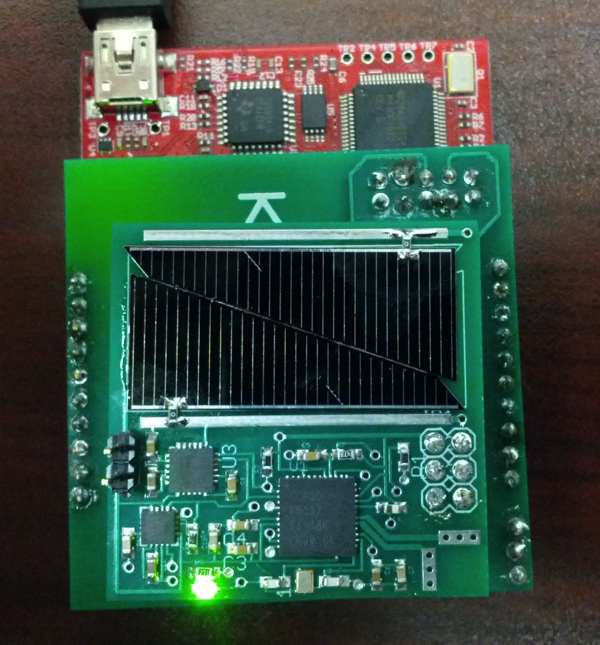

The starship hardly looks out of the ordinary on Earth—it’s simply a PCB, or printed circuit board, much like the ones in our phones, tablets, TVs, cars, and every other piece of electronics. Fitted with some special modifications, like a sail that catches light to propel the spaceship and sensors to accumulate data, the PCB would be able to withstand 30,000 Gs of acceleration and travel at 20 percent the speed of light.

Zac Manchester, the inventor of this PCB-starship, calls it the KickSat Sprite. But the original design wasn’t actually destined for interstellar travel. The first few missions dreamed by Manchester involved low-Earth orbit, to test the idea of a tiny fleet.

“A lot of really interesting and weird things happen when you make satellites really small,” Manchester said. “Things like solar sailing, that people have been trying to do for decades on big satellites, get almost trivially easy when you get really tiny.”

The small size of the satellite also makes the overall cost more reasonable, says Manchester. He’s able to build the today’s version of the Sprite for between $20 and $30, far cheaper than a traditional satellite’s cost, which can reach in the multi-millions. You can even build a whole fleet of KickSats for less money than a full-sized one. It can be build to carry any kind of small sensor, including thermometers, magnetometers, gyroscopes, and accelerometers.

“If you look at how much they weigh, how much space they take up, and the cost of launching satellites right now, the launch cost is less than $1,000,” Manchester said. “A start-to-finish space mission the cost of a laptop.”

Through his graduate program at Cornell University, and then after garnering funding the successful Kickstarter campaign, Manchester has been able to attempt two missions so far.

In the first mission led by Cornell, the Sprites were mounted to the exterior of the International Space Station to see how they would hold up against the void of space. They held up, although Manchester said they came back “a little toasted.”

The second mission was funded by Kickstarter and took place on April 18, 2014, and entailed a small pod of Sprites being released while a satellite orbited Earth. The pod, called a KickSat, would open and release the Sprites. However, the deployment of the Sprites was delayed roughly two weeks to make sure the area was clear for a Soyuz launch. During this time, there was a glitch with the the pod’s opening mechanism, and the mission failed. The KickSat burned up in the Earth’s atmosphere on May 14, 2014, just a day before Popular Science first covered the project.

However, all this put Manchester on Milner’s radar. Manchester doesn’t know for sure how it happened, but he thinks that Pete Worden, former director of NASA’s Ames Research Center, might have recommended KickSat, as he oversaw Manchester’s work while at Ames, and is now joining Milner’s project.

No matter how Milner found out about KickSat, he clearly saw something big in the idea. About a month ago, the billionaire invited Manchester to his home for lunch, to talk about the idea.

“It was a tad intense,” Manchester said. “I think I talked the entire time, but it was because Yuri kept asking questions. He would a technical question and I would answer, and he would have another question immediately after it.”

In our conversation with Milner, he said that the inventor of the spacecraft would be joining the team, and Manchester said he was “on board,” but that the whole process was still unfolding.

Despite this recent development, Manchester is still shooting for a second launch this summer, for KickSat 2. He already has secured a launch with NASA’s CubeSat Launch Initiative, which gives launch opportunities to research projects focused around tiny satellites.

So whether it ever makes it to Alpha Centauri or not, it seems safe to say that the KickSat and other craft like it will play an important role in space exploration and research in the coming years.