Popular culture depicts medieval warhorses as majestic creatures—tall, muscular, and powerful, with shining knights atop. But new research shows that the steeds of the Middle Ages were likely much smaller than we would expect.

A team of zooarchaeologists in the United Kingdom analyzed 1,964 horse bones from 171 different archaeological sites dated between 300-1650 C.E., and compared how those remains measure up to the horses of today. The horses of the Middle Ages, they found, were much slighter than their modern-day descendents—usually no more than pony-size. Their findings were published last August in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology.

Whether an equine animal is classified as a horse or pony depends entirely on its size. The animal is typically measured from the ground to the ridge between their shoulder blades, in units called hands, with one hand equaling 4 inches. Modern horses stand at at least 14.2 hands, or 4-foot-10-inches, and racehorses and showjumpers are often taller, around 16 or 17 hands. The archaeologists found that English medieval knights led their charges on horses shorter than 14.2 hands tall—today they would be classified as ponies, not horses.

Yet those horses had a sizable impact, despite their short stature. “The warhorse is central to our understanding of medieval English society and culture as both a symbol of status closely associated with the development of aristocratic identity and as a weapon of war famed for its mobility and shock value, changing the face of battle,” University of Exeter archaeologist and principal investigator for the research, Oliver Creighton, said in a statement.

[Related: Scientists are trying to figure out where the heck horses came from]

The authors note in their paper that while these horses may seem too small to engage in battle, historical records are “notably silent on the specific criteria which defined a warhorse.” They add that it is likely “throughout the medieval period, at different times, different conformations of horses were desirable in response to changing battlefield tactics and cultural preferences.” Size, in other words, was not the only thing that mattered. Medieval horses were probably bred and trained with a combination of biological and temperamental factors in mind, which may have shifted as military strategies changed, requiring the animals to perform different functions.

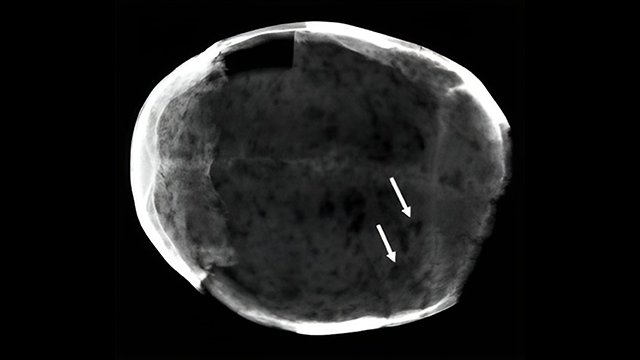

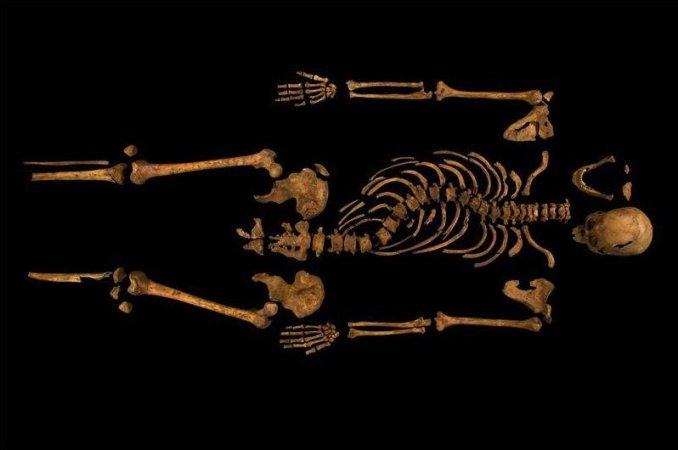

But it’s also impossible for archaeologists to definitively identify which horse remains belong to steeds who engaged in combat. Without other indications like specific burial records, there’s no way to discern the remains of a warhorse or a farm horse based on bones alone, even if researchers had access to whole skeletons, rather than the single bones they usually get from an individual site.

To tease out more of these horses’ histories, the authors write that they’ll need to conduct more detailed investigations on how bone shape differs between individual horses. Future studies may also use ancient DNA analysis to track ancestry and observe how English horse genomes changed over time.